The 125-Year-Old Safety Penalty

It's rare to pinpoint an individual play that sparked a 125-year-old football rule, but I believe this story identifies one. The evidence, though circumstantial, is compelling. The story also involves two figures who played significant, if not towering, roles in football's development. And, the play took place at the prep level, adding an intriguing twist to its significance since few college football rules were driven by the high school game.

The play in question occurred in the Germantown Academy-Haverford School game on Friday afternoon, October 20, 1899. Both schools are prominent Philadelphia-area institutions with endowments that would make a small college proud. They still compete in football with their next game coming on October 10. Germantown's alums include Frederick Winslow Taylor, the founder of Scientific Management, Bill Tilden, and Bradley Cooper. Haverford touts former students like Steve Sabol of NFL Films, two-time Medal of Honor recipient Marine Corps Maj. General Smedley Butler, and Bert Bell, former Philadelphia Eagles owner and NFL Commissioner. We'll come back to the last one in a minute.

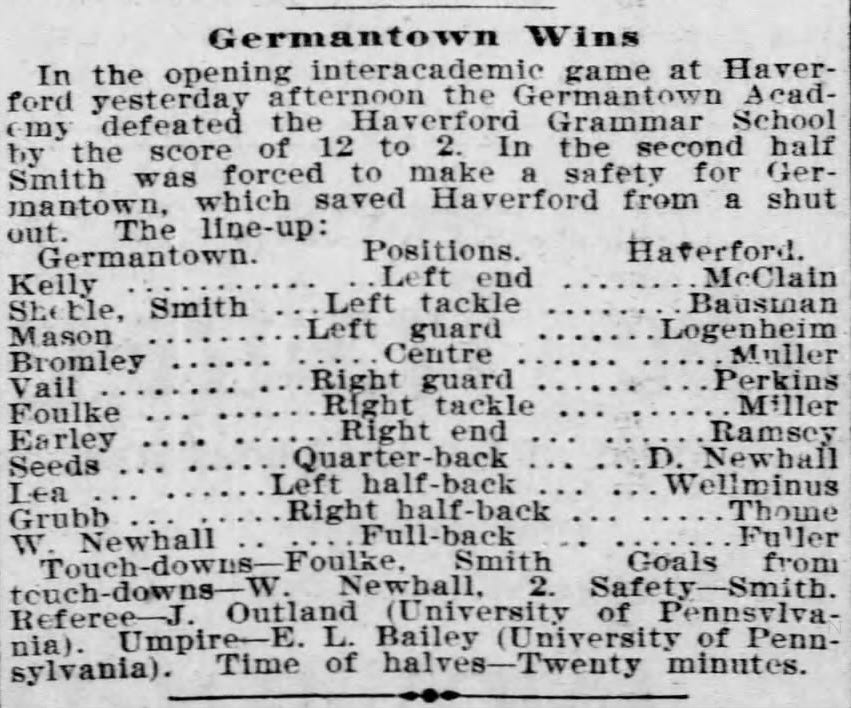

The play unfolded when Haverford kicked off to Germantown to start the second half. The ball went behind the goal line, where Smith, a substitute tackle for Germantown, picked it up. Instead of downing the ball for a touchback, Smith tossed it to his teammate Lea, who was standing on the 5-yard line, turning the play into a forward pass. Forward passes were not yet legal in 1899, and even today, they are not legal on kicking plays, so the referee paused the game to consider whether a foul had occurred and, if so, what the penalty should be.

The referee was John Outland, the chap for whom the Outland Trophy is named, then playing his seventh football season at his third college, Penn. While Outland, a two-time All-American, knew his football and thought Smith had committed a foul, he was confused about whether a forward pass thrown from behind the goal line constituted a penalty. Everyone knows the answer to that question today, but the rules were not so clear in 1899. Recall that football did not have end zones until 1912. The area behind the goal line was called "in goal," lacked an end line, and was ill-defined in the rule book.

One thing the rule book was clear about in 1899 was that forward passes on the field of play were fouls, with the offending team losing possession at the spot of the foul. However, Smith did not throw his forward pass in the field of play. He threw it from “in touch.” Outland might have awarded Haverford a touchdown since enforcing the penalty as normal would have given Haverford the ball behind Germantown's goal line. He might have called the play a touchback, but Smith did not touch the ball down behind the goal line. Instead, Outland stepped outside the rule book and ruled the play a safety.

While Smith screwed up by throwing a forward pass, he later redeemed himself by running for a touchdown on the way to a 12-2 victory. In fact, both of Germantown's touchdowns were scored by tackles that day, which was not unusual then since tackle-around plays were in every team's repertoire.

That might have been the end of things, an odd play in a prep game soon forgotten. Instead, the play gained notoriety by being mentioned in a nationally syndicated article describing unusual plays and gaps in the football rule book revealed during the 1899 season.

Here’s where more circumstantial evidence enters the picture. A likely reason the play became influential was John C. Bell, Penn's football committee chairman (akin to a volunteer athletic director) and a prominent lawyer who later served as Pennsylvania's Attorney General. Bell played football at Penn in 1884 and was the second longest-serving member of the college football rules committee, junior only to his colleague, Walter Camp. Bert Bell, the NFL commissioner mentioned earlier as a Haverford alum, was John C. Bell's son, so it does not stretch the imagination to think that John C. Bell became aware of an odd play and the gap in football’s rules directly from John Outland or others in the Haverford, Penn, or Philadelphia football communities.

About six months after the play occurred, John C. Bell was among the six Football Rules Committee members who made several rule changes for the 1900 season. One change added a paragraph to the definition of a safety, indicating that fouls committed behind a team's goal line would henceforth constitute a safety, a rule that has remained in place since then.

Of course, you can believe what you want about whether the events of the 1899 Germantown Academy-Haverford School game led directly to a 125-year-old rule, but I know on which side of the goal line I stand.

Click here for options on how to support this site beyond a free subscription.

And this was the rule that Iowa knew they would look to exploit for generations to come.

Well written!

Superbly written.