Today's Tidbit... 1950s Bell & Howell Tips On Football Home Movies

We are awash in football video content, covering the game from the youth level to the NFL. However, if you played high school football before the mid-1980s when consumer-oriented camcorders became popular, your glory days are likely unavailable on film or video today. Your coaches may have had a game film, but you saw that film once with the team and never again.

Regular readers may recall a Tidbit from August 2024 concerning a 1908 RPPC showing a Missouri high school game that went down a rabbit hole regarding the Graphlex camera line. This story sends us spelunking again as we cover the intersection of football and amateur motion pictures in days gone by.

Amateur or consumer-oriented movie cameras arrived in the mid-1930s, but during the Great Depression, they were in the hands of wealthy early adopters. It was not until the years after WWII that their use became more mainstream.

Like any new technology tossed into consumers' laps, people needed to learn how to use their movie cameras in general and for specific applications. That led a major manufacturer, Bell & Howell, to produce a 16-page pamphlet in 1951, Tips On Making Your Football Movie.

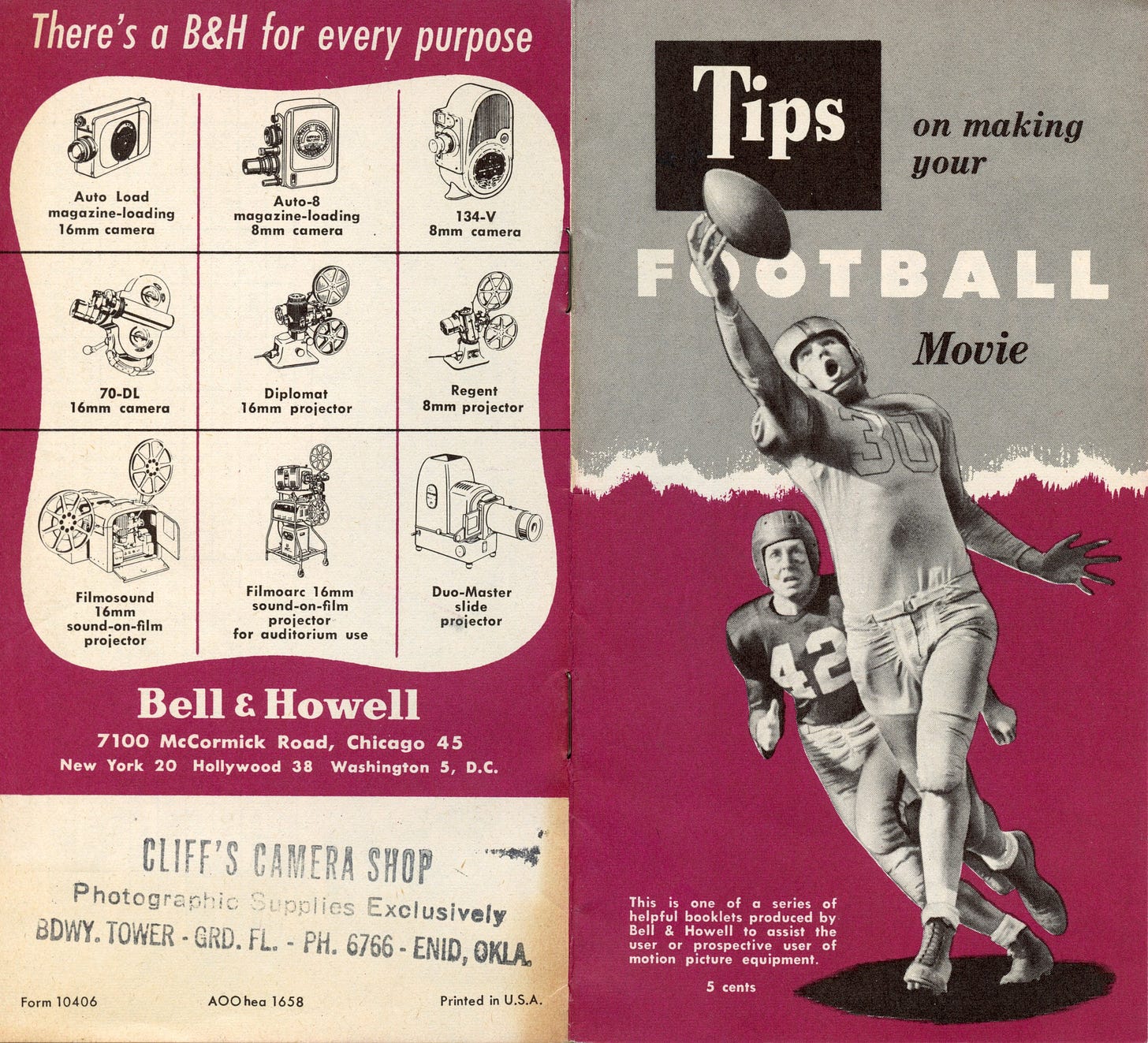

The Bell & Howell pamphlet has a great cover image of a plastic-helmeted receiver reaching for a ball as a leather-helmeted defender pursues him. The text at the bottom mentions "motion picture" equipment, while the title at the top uses the nickname "movie."

The back of the pamphlet shows Bell & Howell's camera and projector offerings, including three cameras featured inside. The stamp at the bottom indicates the pamphlet came from a shop in Enid, Oklahoma. Yes, there once were shops in most neighborhoods and towns that sold cameras, processed film, and printed photographs for consumers.

Bell & Howell confirmed that football is photogenic if you have the right equipment, technique, and approach.

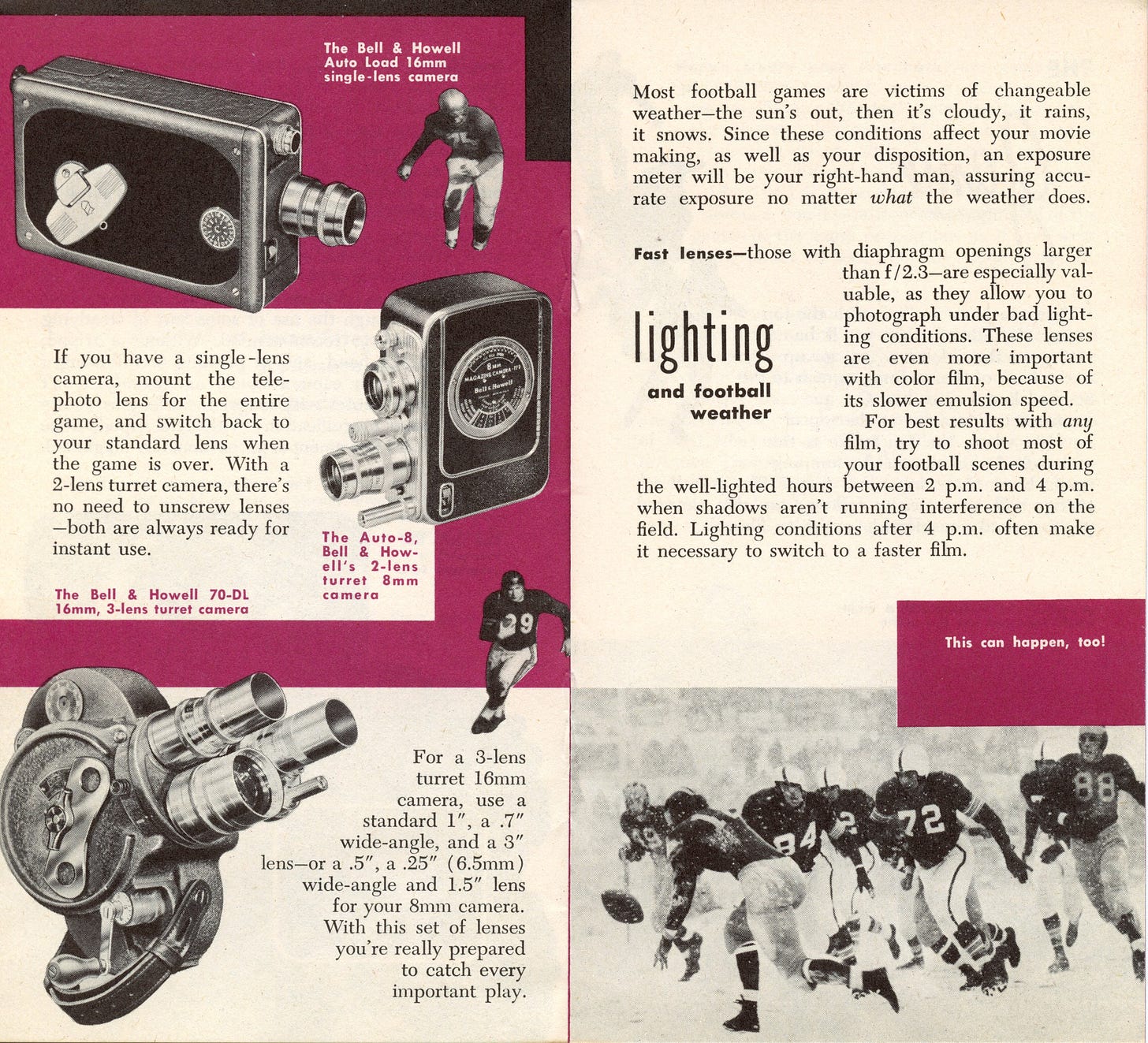

It was more difficult to focus still or moving cameras then than now. Neither auto-zoom nor zoom buttons existed. Getting a focused shot required manually adjusting the lens or changing lenses by unscrewing your camera's single lens and replacing it with another. If you spent the big bucks on a turret or turnstile camera (as shown in the image below), you could press a release button to quickly rotate and swap lenses. (Abraham Zapruder used a single-lens Bell & Howell home movie camera to capture the only footage of JFK's assassination.)

Cameras also did not automatically adjust for lighting conditions, requiring additional adjustment when the sun went behind a cloud or for rain and snow. The pamphlet suggests you can solve that problem by filming on a sunny day between 2 and 4 p.m. when shadows do not wreak havoc with the images.

The pamphlet then offers six pages of advice for movie makers on combining photographic know-how and football insight to anticipate getting the right shot at the right time.

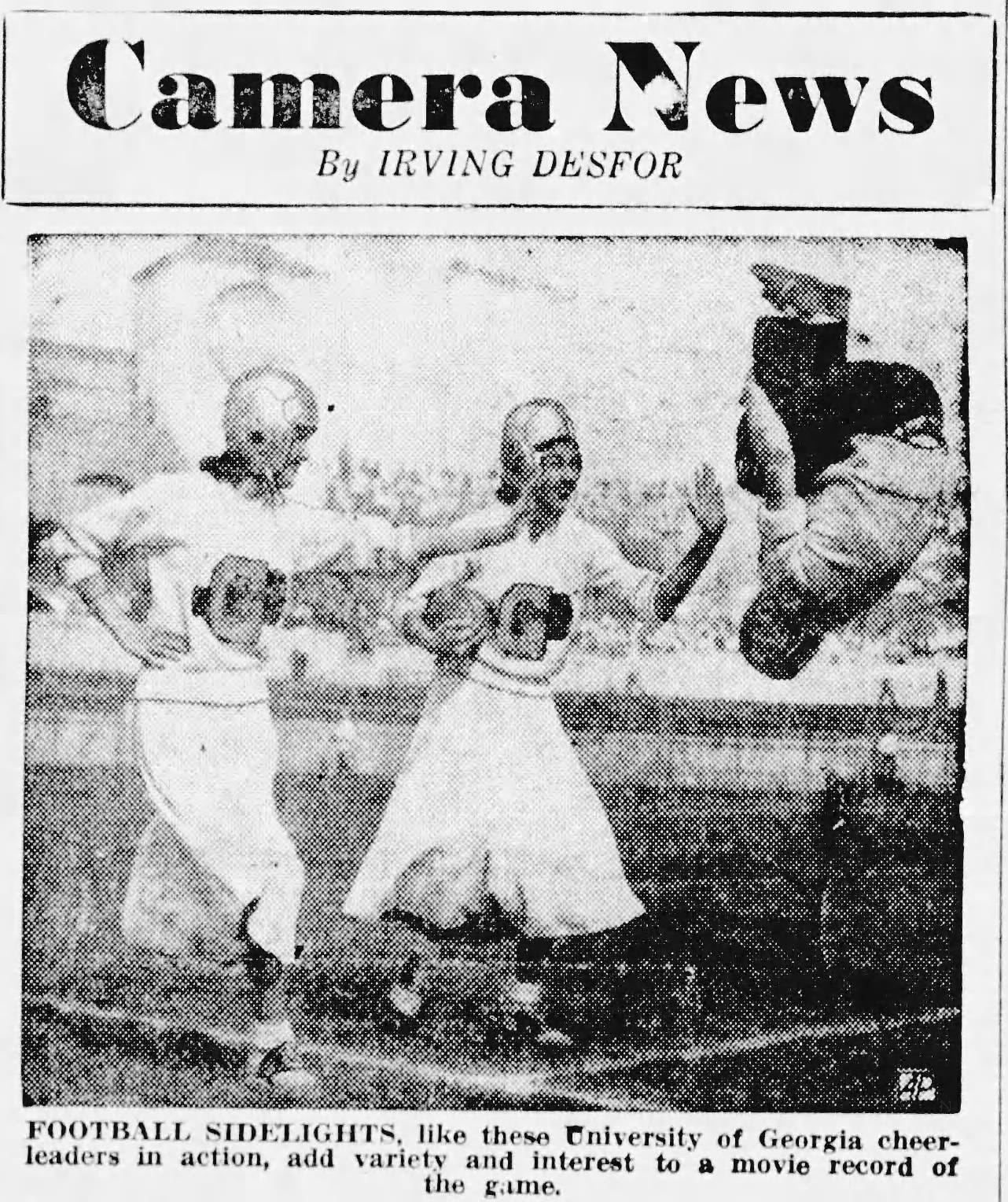

Bell & Howell was not alone in providing advice on filming football games. The November 1949 issue of Home Movie offered plenty of advice on filming games, suggesting that you add color to your home movie by including shots of the crowd and cheerleaders.

A syndicated news column offered similar advice:

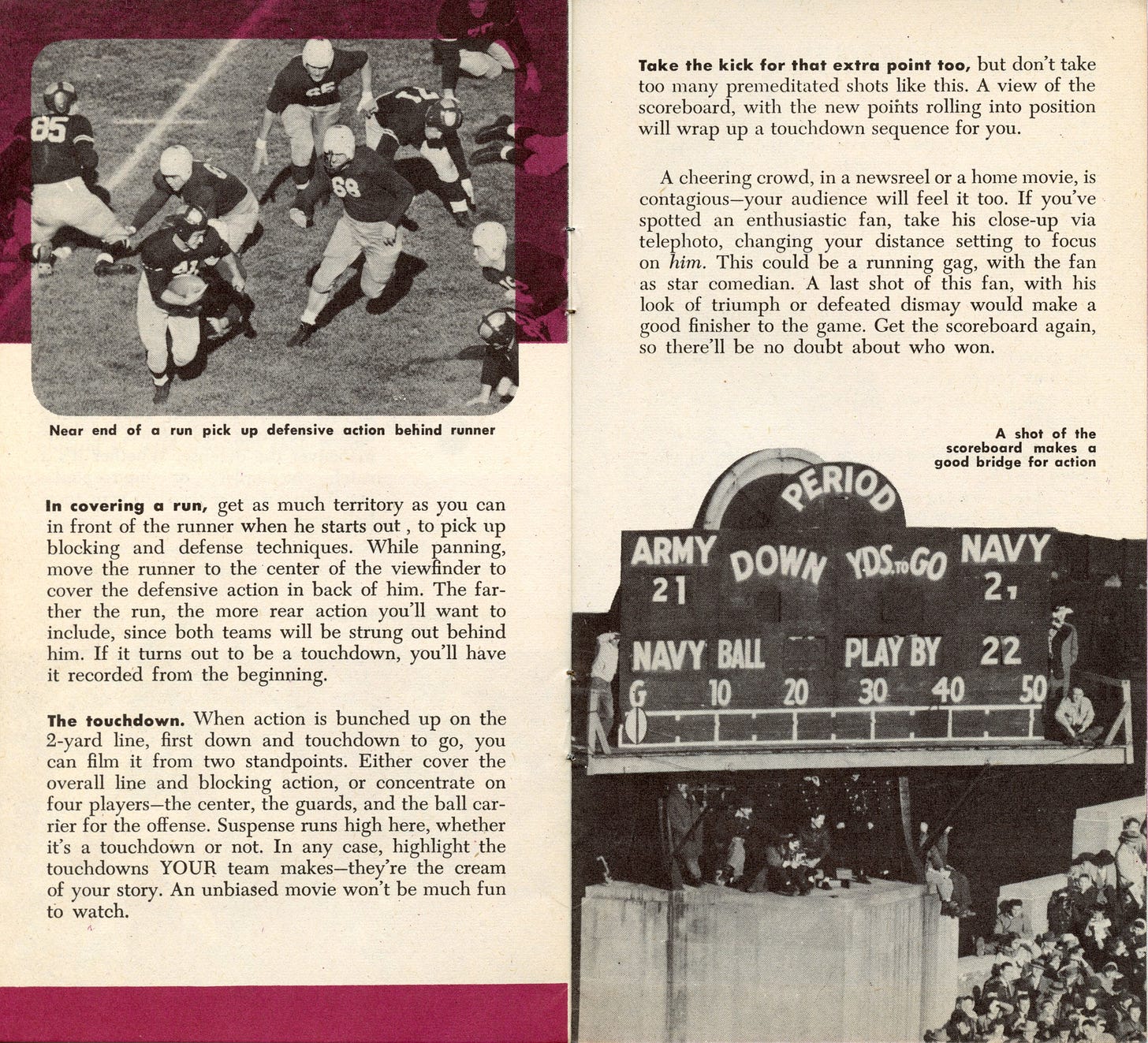

Likewise, the Home Movies article, Tips On Making Your Football Movie, advises filming the family getting in the car or onto the streetcar, and getting shots of the scoreboard, vendors, and the banners flying atop the stadium.

Later advice makes it clear that some percentage of early home movie enthusiasts edited their home movies, much like putting together a newsreel. Editing a movie required cutting the film apart with a splicer that created tabs and sockets, much like a jigsaw puzzle, to reconnect the segments. The same thing happens with TikTok videos today, but the home movie folks had fewer tools and more work to put one together.

Amateur movie cameras also handled only two to four minutes of film per cartridge, so capturing the right plays required knowledge of the game or luck. Either way, the pamphlet suggests shooting at least seven seconds for each scene.

Unfortunately for those who enjoy football history, amateur movies represent a donut hole in the game. Their predecessors, RPPCs and generic photos, might sit in Grandma's forgotten album for 100 years, but once found, the image was right there on photographic paper with no additional technology needed.

On the other hand, someone who found 16 mm home movies of Great Uncle Joe's high school games needed a movie projector to view them. Since the film also becomes brittle with time, people likely threw away many home movies over the years. Hopefully, at least a handful ended up in university archives or other collections that digitized and made them publicly accessible, though I have yet to encounter one.

Other stories related to football, photography, and film include:

Click Support Football Archaeology for options to support this site beyond a free subscription.