Today's Tidbit... A History of Goal Posts

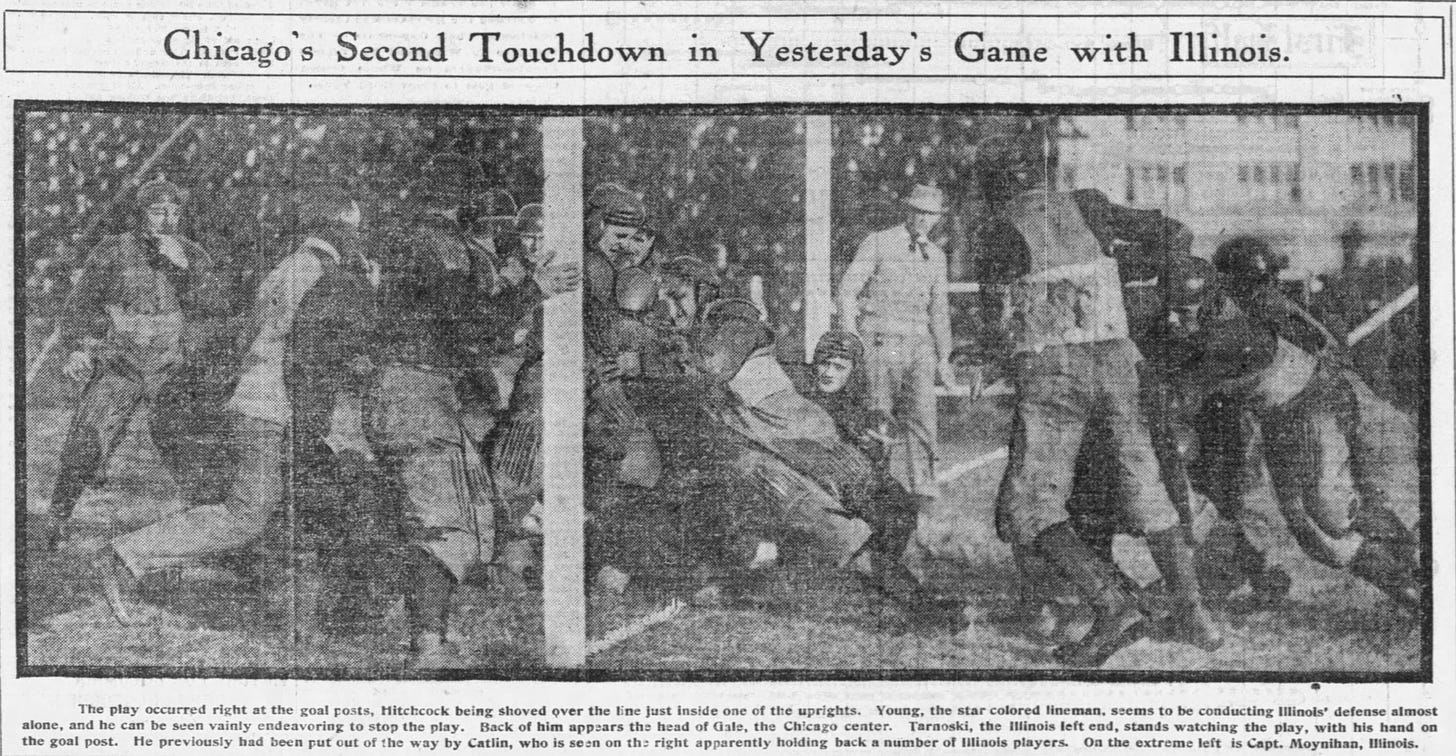

There was trouble in River City back when goal posts stood on the goal line, mostly because they got in the way. Ball carriers sometimes ran into them, doinking back onto the field and failing to score, while defenses braced themselves against the posts to impede blockers and ball carriers.

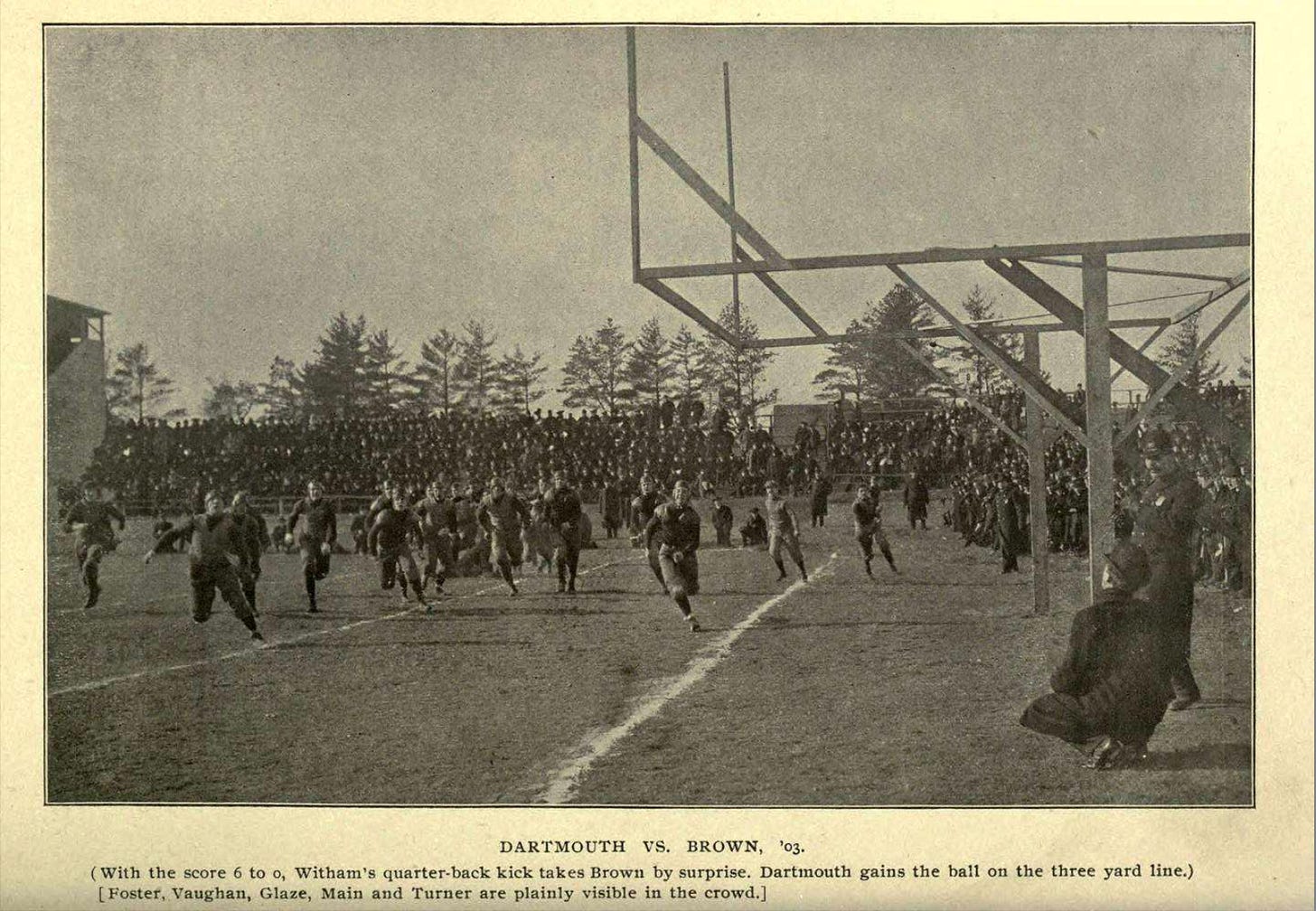

Poor Harvard suffered such problems against Yale in 1899 and 1903. The details about the 1899 game vary a bit, but the core story is consistent. On their third and final down with the ball sitting between the goal posts on Yale’s 2-yard line, the Crimson gave the ball to Ellis, a halfback, who ran directly toward a goal post, right into a mass of Yale defenders sturdied by the wooden post immediately behind them. Harvard did not cross the goal line, so the game ended in a scoreless tie, the only blemish on Harvard’s 1899 season.

Then, in 1903, Harvard had the ball on third down near the goal posts, this time on Yale’s 3-yard line. Once again, they gave the ball to a halfback, who ran toward a goal post, only to run into it, and doink back onto the field, making it Yale’s ball, as the Elis went on to a 16-0 win.

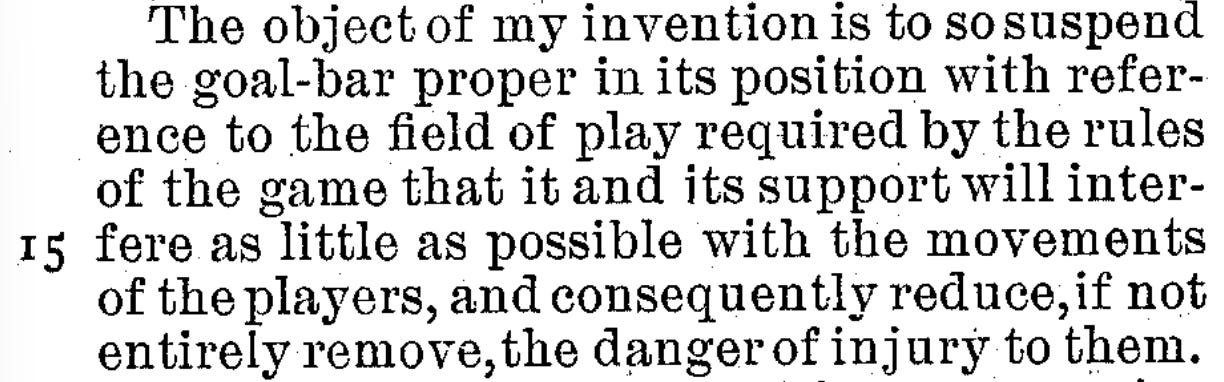

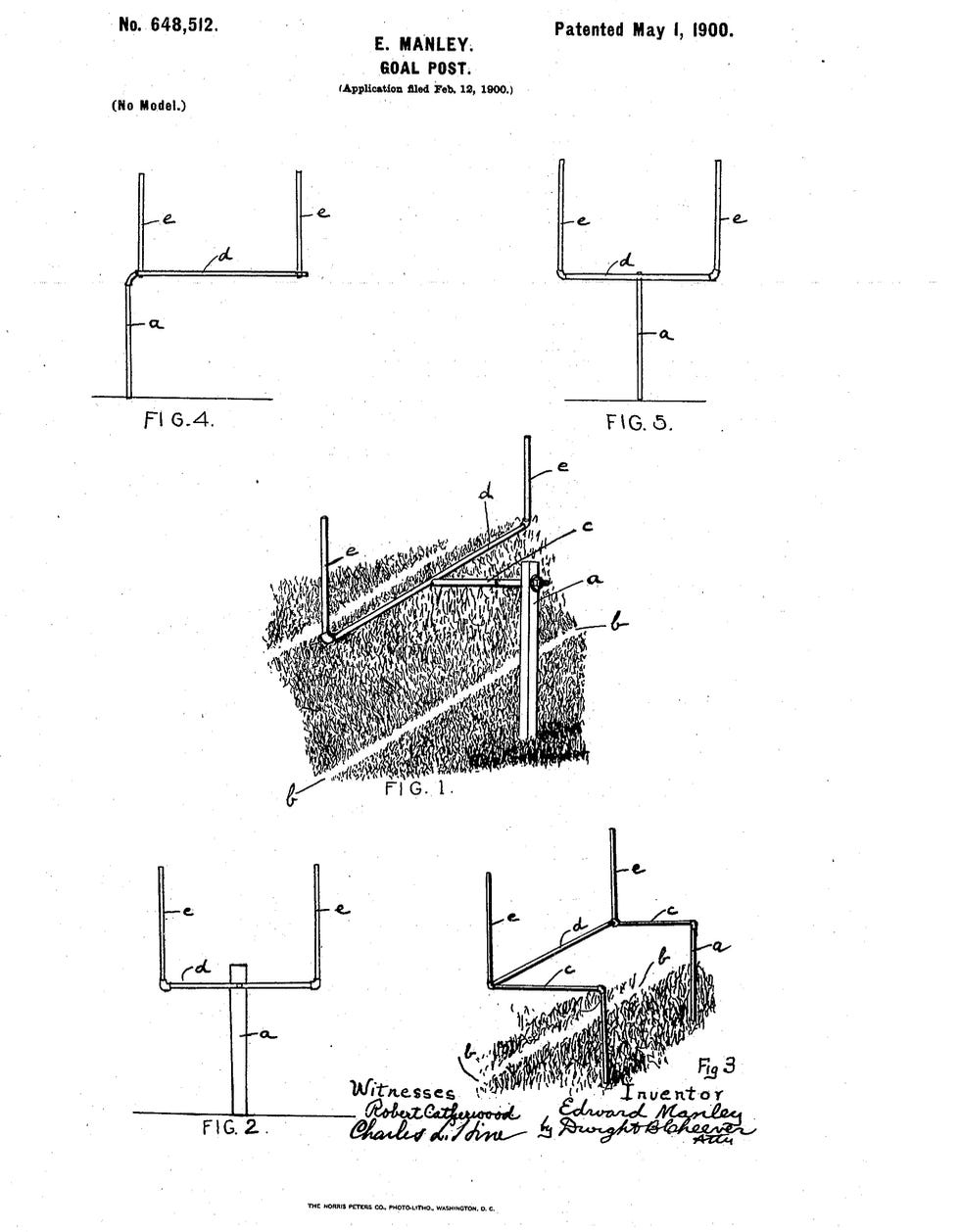

Despite the Crimson failing twice in similar circumstances, you can only fool some Harvard men once, and one of those one-time guys was Edward Manley. Manley filed for a patent on February 12, 1900, for a new type of goal post that might have changed the outcome of the 1899 game. Manley’s patent application described the new goal post design as serving two purposes: 1) to have the goal posts interfere with play as little as possible, and 2) to eliminate the safety risk posed by goal posts located on the goal line.

How did Manley solve both problems? Standard goal posts looked like the capital letter “H.” They had two posts with a crossbar ten feet off the ground, above which rose uprights 18 feet 6 inches apart. His design was different. It called for one post (or two), several yards behind the goal line, from which extended a crossbar and uprights directly over the goal line.

With his design, the goal posts would not interfere with play or represent a safety risk. It was a brilliant idea, especially in the days before the forward pass was legal.

Despite the brilliance of Manley’s idea, I don’t recall seeing a period image of an installed goal post that followed his original “safety goal post” design. However, his idea still had an impact. Manley was a teacher at Chicago’s Englewood High, but he clearly did not teach or understand physics. All goal posts of the era were wood, and his single-post design did not provide the support needed to keep a crossbar and two uprights standing, so they built safety goal posts with two posts, plus additional bracing.

Manley’s safety goal posts solved both the interfering with play and safety problems. Still, many locations remained loyal to H-style goal posts, perhaps because Manley held a patent and charged teams $50 per installation ($1,626 in 2025 dollars). Whatever the reason, some schools chose not to address the inference issue, while many addressed the player-safety issue by padding the goal posts, for which Amos Alonzo Stagg is often credited with originating the idea. Now, I like old Lonny Stagg more than most guys, but I have found no evidence to suggest he was the first goal post padder.

To the contrary, the idea of padding goalposts was around by 1896, following a Brown player being injured after running into a post. The first instance I found of a goal post actually being padded came at the home field of the Steeltown (PA) YMCA team. Who knew?

Moreover, if Stagg was the father of the padded goal post, he did not think much of his child since UChicago’s Marshall Field goal posts remained unpadded as late as 1905.

A few news reports indicate that Stagg tied mattresses to Chicago’s goal posts when they hosted Minnesota in 1906, and a 1909 RPPC confirms they padded them when they hosted the Badgers in 1909. That all suggests Stagg was a paddee, not the padder.

A separate issue about goal posts was whether the crossbar and uprights should hang above the goal line or the end line. The NCAA moved them to the end line in 1927, before football fields had hash marks. They thought that shifting the goal posts to the end line provided better angles for teams that penetrated their opponents’ 20-yard line but had the ball toward one sideline or the other.

The NFL, which followed college rules until 1932, moved the goal posts back to the goal line in 1932 after having too many tie games in 1931. Their thinking was that placing the goal post ten yards closer would make it easier for kickers to score.

Both systems went their merry way until the arrival of soccer-style kickers, who could convert even when booting the ball from the next county, leading the NFL to move the goal posts back to the end line in 1974.

By then, Canada had made its most significant contribution to the North American goal post game. Joel Rottman, a Canadian media distributor, and Jim Trimble, an American and recently-fired Montreal Alouettes coach, teamed up to develop the Tele-Goal. The Tele-Goal mirrored Edward Manley’s 1900-patented single-post design, except they made it of aluminum, which allowed the Tele-Post to have limited bracing and uprights extending 20 feet above the crossbar. The NFL adopted the Tele-Post for the 1967 season, and so has nearly everyone else since then.

Despite goal posts being among the most straightforward elements of the game, they allowed for innovations to address the ills they introduced into football. We may soon see electronic tracking of field goals and extra points, replacing officials’ judgment, as is happening with baseball’s strike zone, but I suspect it will be a while before goal posts disappear from football fields. You gotta have something to aim for.

Regular readers support Football Archaeology. If you enjoy my work, get a paid subscription, buy me a coffee, or purchase a book.

Trimble was the losing coach in at least one Grey Cup that my home town Winnipeg Blue Bombers won in the 50s and 60s. Somebody in Winnipeg even cut an audio record about it, a parody of the Kingston Trio's "Tom Dooley" telling him to "eat your humble pie"!

Coming of age as I did in the wide goal post era, I was shocked when I learned the current width is the original width. Partly because I seem to recall the conversation at the time was about moving to the NFL width, not the 1870s width.

We're just a few years away from the second narrow goal era having existed as long as the wide goal era.