Today’s Tidbit... A Puncher’s Chance To Recover Fumbles

Football instituted a rule in 1929 that prevented defenses from advancing fumbles, a rule that remained in effect at the college level until 1990. They justified the rule as encouraging offenses to attempt riskier laterals, since offenses would not suffer the terrible fate of seeing fumbles scooped up and taken in for scores. The story linked below discusses how the hook-and-lateral and triple hook-and-lateral plays gained popularity after implementing the rule.

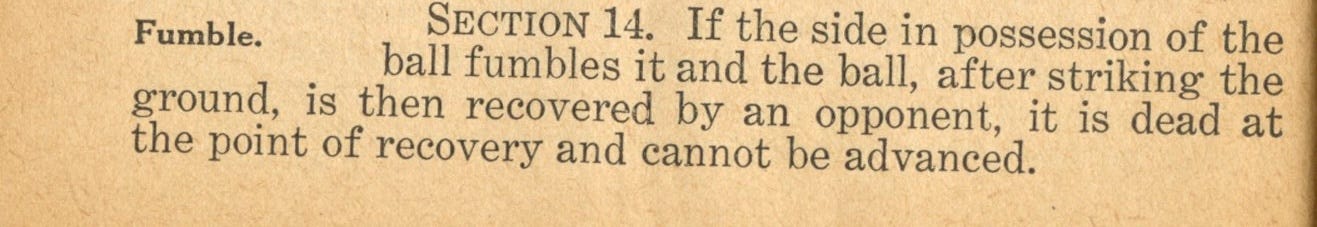

However, there was an exception to the rule, as seen in the 1929 rule book.

The exception arises in the phrase “after striking the ground,” which allows for fumbles caught in the air or taken from the grasp of the ball carrier to be advanced by the defender. A later amendment described the ball being taken from the runner’s grasp as having been “snatched” and, more popularly, as being “stolen,” with the rule itself becoming known as the “stolen ball” rule.

Before the non-advancement rule arrived, coaches instructed players to punch the ball out of the runner’s grasp, with UPenn known for its proud punching tradition. However, the 1929 rule placed greater emphasis on tackling the ball rather than punching it out, although some considered both practices unsportsmanlike. Rules prohibiting both were proposed but never approved.

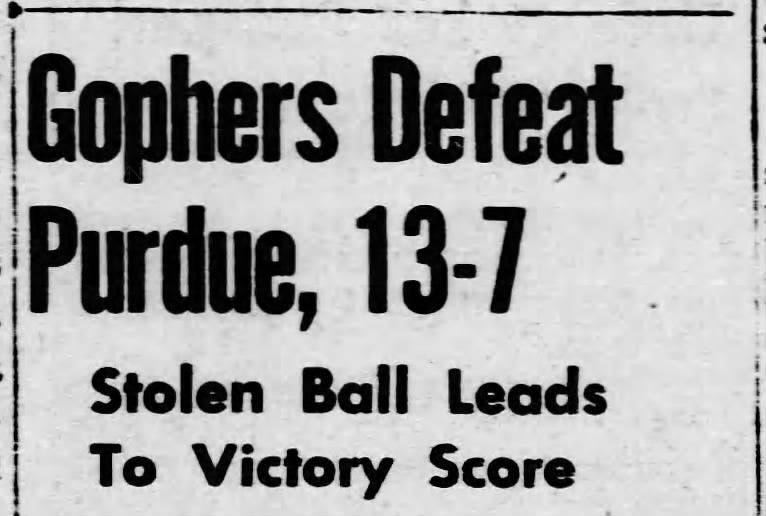

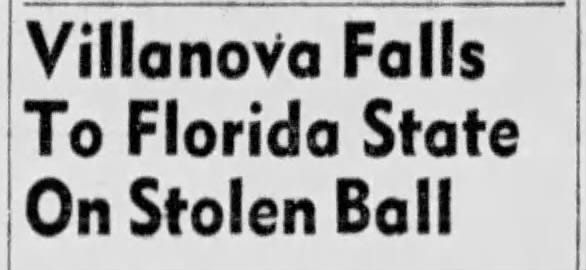

Despite teams working on stealing the ball, stolen balls were rare between 1929 and 1989, so they were celebrated more than they are today.

Stealing the ball and taking it in for the score was considered the mark of a great athlete, with a few emerging in the national scene based on such plays. Chuck Taylor, a two-time All-American and no relation to the Converse Shoe salesman or his eponymous shoes, grabbed the ball from USC’s Mickey McCardle in 1940 and raced 40 yards for a Stanford touchdown to help send the team to the Rose Bowl. (He later became the first to play, coach, and be the athletic director for a Rose Bowl team, all of which he did at Stanford.)

Sometimes the future famous players were the snatchee rather than the snatcher. Such was the case when Notre Dame’s Jim White, himself an All-American, stole the ball from Army’s future Heisman Trophy-winner Glenn Davis during their 1943 game, which contributed to Notre Dame’s win as they marched to the national championship.

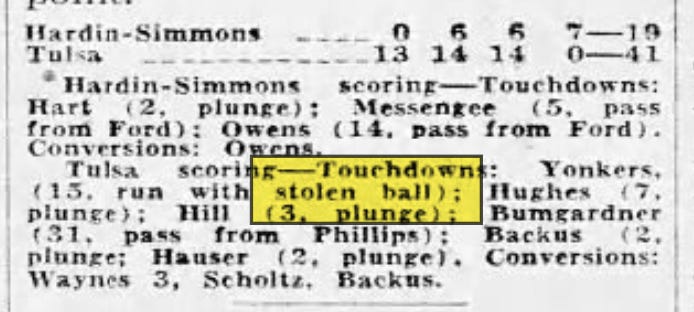

Of course, obscure players who time has forgotten stole many balls. In one case, the newspapers memorialized a Tulsa player named Yonkers for all time by noting in the box score that he scored on a stolen ball.

After the 1990 rule reversal, defenses advancing fumbles became sufficiently common that we invented the term “scoop and score,” which first appeared in print in 1996. By 2020, the YouTube site, PSC Highlights, compiled a video of every scoop and score in games involving at least one FBS team. The video lasts more than 15 minutes so it is fair to say they are no longer the rarity they once were.

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to donate a couple of bucks, buy one of my books, or otherwise support the site.

Those interested in the origins of football terminology, such as scoop and score, will enjoy reading Hut! Hut! Hike!

Being an old time football historian, I was surprised to see you use “hook and lateral” rather than “hook and ladder”!