Today's Tidbit... A Short History of Onside Kicks

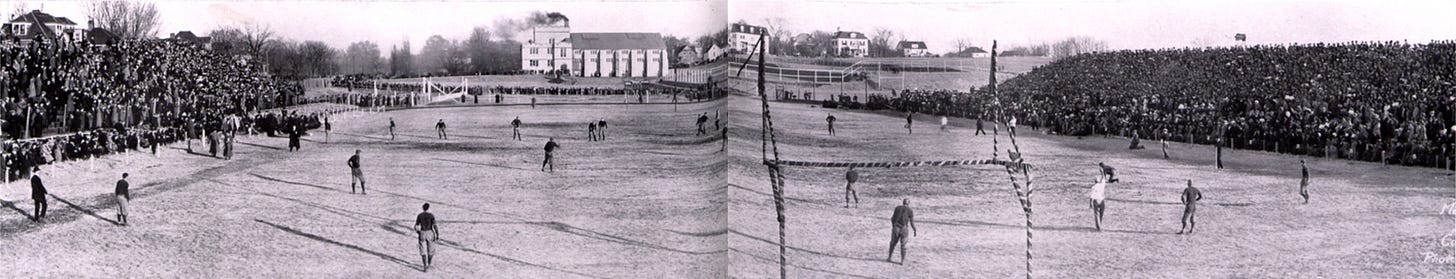

The original flying wedge debuted in 1892. A previous article described the play and its demise when an 1894 rule required the kickoff to travel 10 yards before the kicking team could recover the ball. That rule led most kicking teams to boot the ball as far downfield as possible, hoping to tackle the return man inside the 30-yard line.

In turn, most receiving teams positioned one player 10 or 15 yards from the kicker and spread his ten teammates further back to receive the kick or form a wedge in front of the returner.

From the beginning, coaches recognized that the receiving team's formation made them vulnerable to onside kicks, but few teams executed them. Onside kicks go unmentioned in most coaching books of the time. The bible of kicking, Kicking the American Football, by Leroy N. Mills, doesn't mention the onside kick, and Bob Zuppke, who had something to say about almost everything, offered:

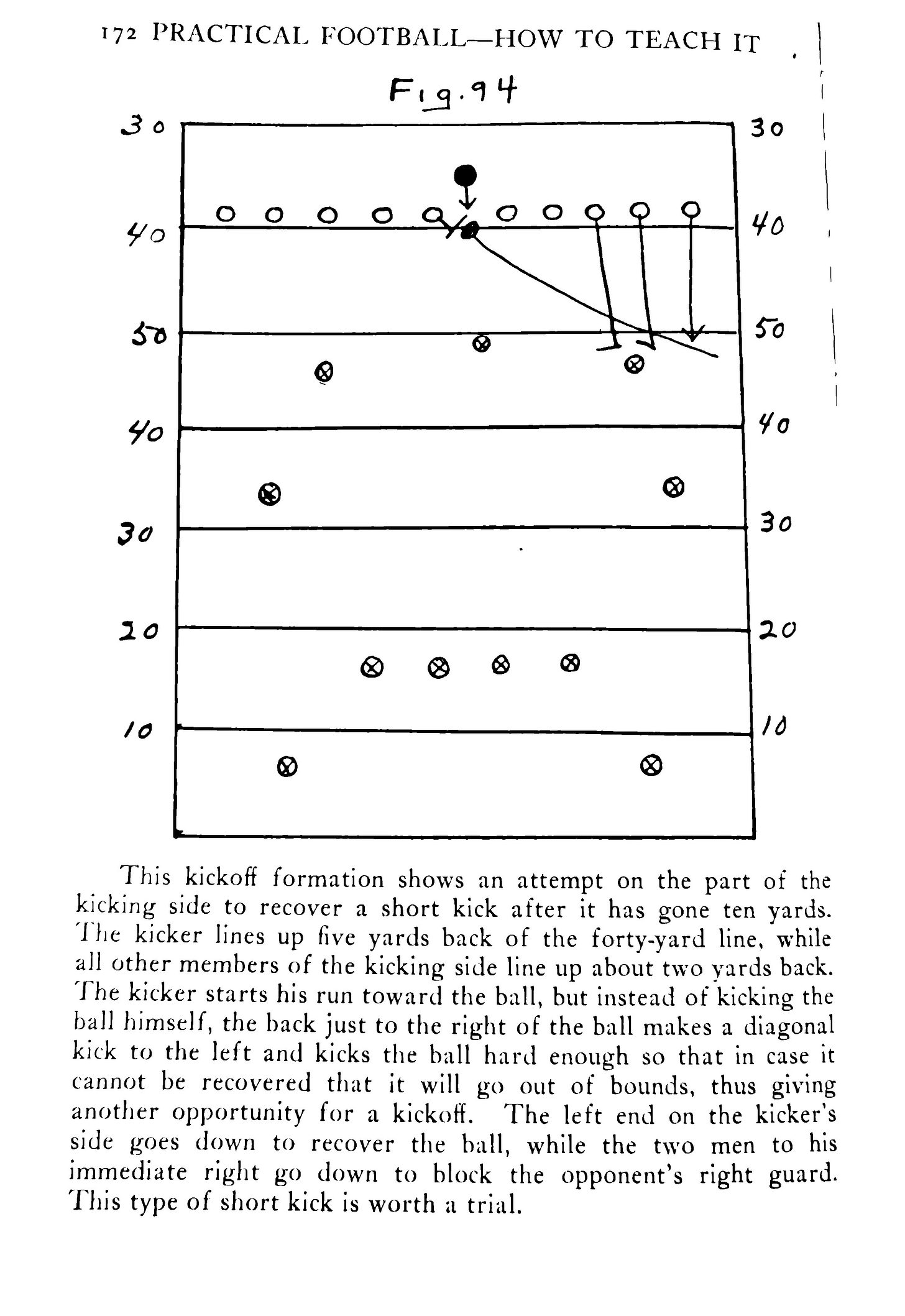

Short angular kicks to the area in front of the kicking side's fast runners are apt to be successful. One or two players may be used to block the near opponents while a teammate recovers the ball.

Zuppke (1924)

That's it. Oddly, from 1892 until 1923, teams regularly executed onside punts (aka quarterback kicks or onside kicks from scrimmage) but seldom onside kicked on kickoffs. Why?

The primary reason teams did not onside kick was conservatism and the perceived value of kicking deep. Bernie Bierman outlined his thinking about kickoffs in Practical Football, saying that a successful kickoff left the receiving team behind their 30-yard line. The conventional wisdom of the time was the field position limited the offense's options, so they often punted on early downs. That meant the original kicking team got the ball somewhere near midfield, leaving them with multiple offensive options. Even when forced to punt, they typically put the original receiving team back inside the 30-yard line. Rinse and repeat.

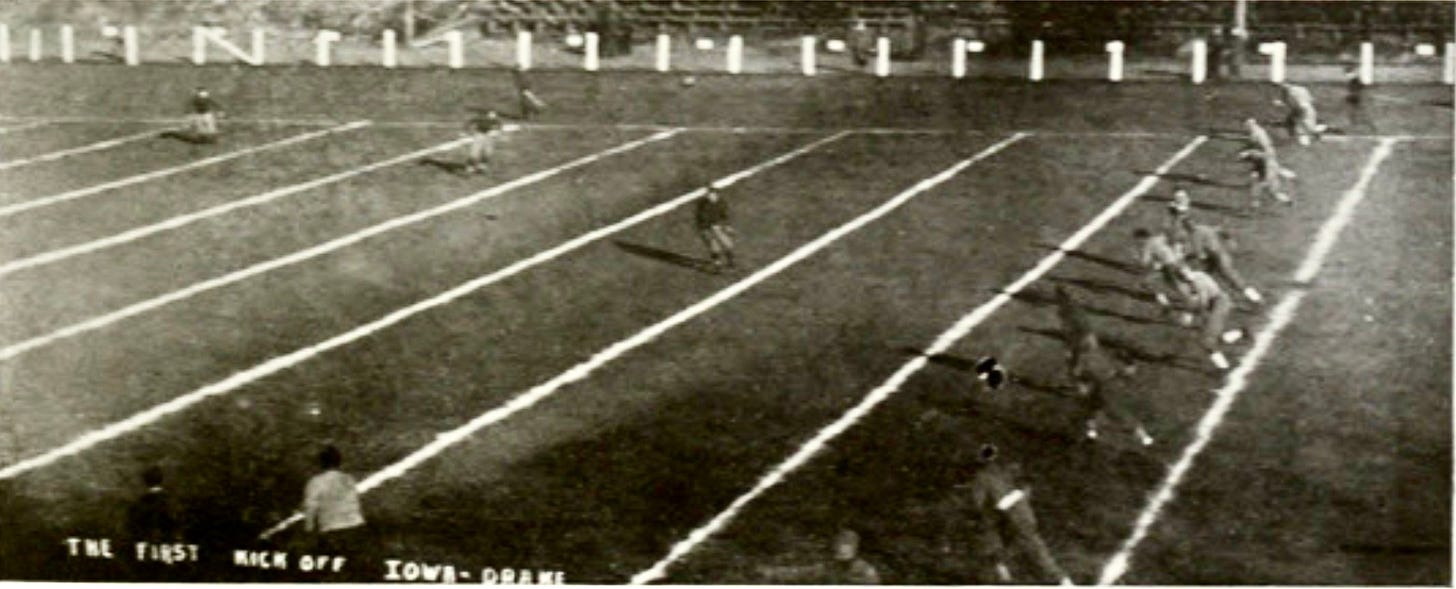

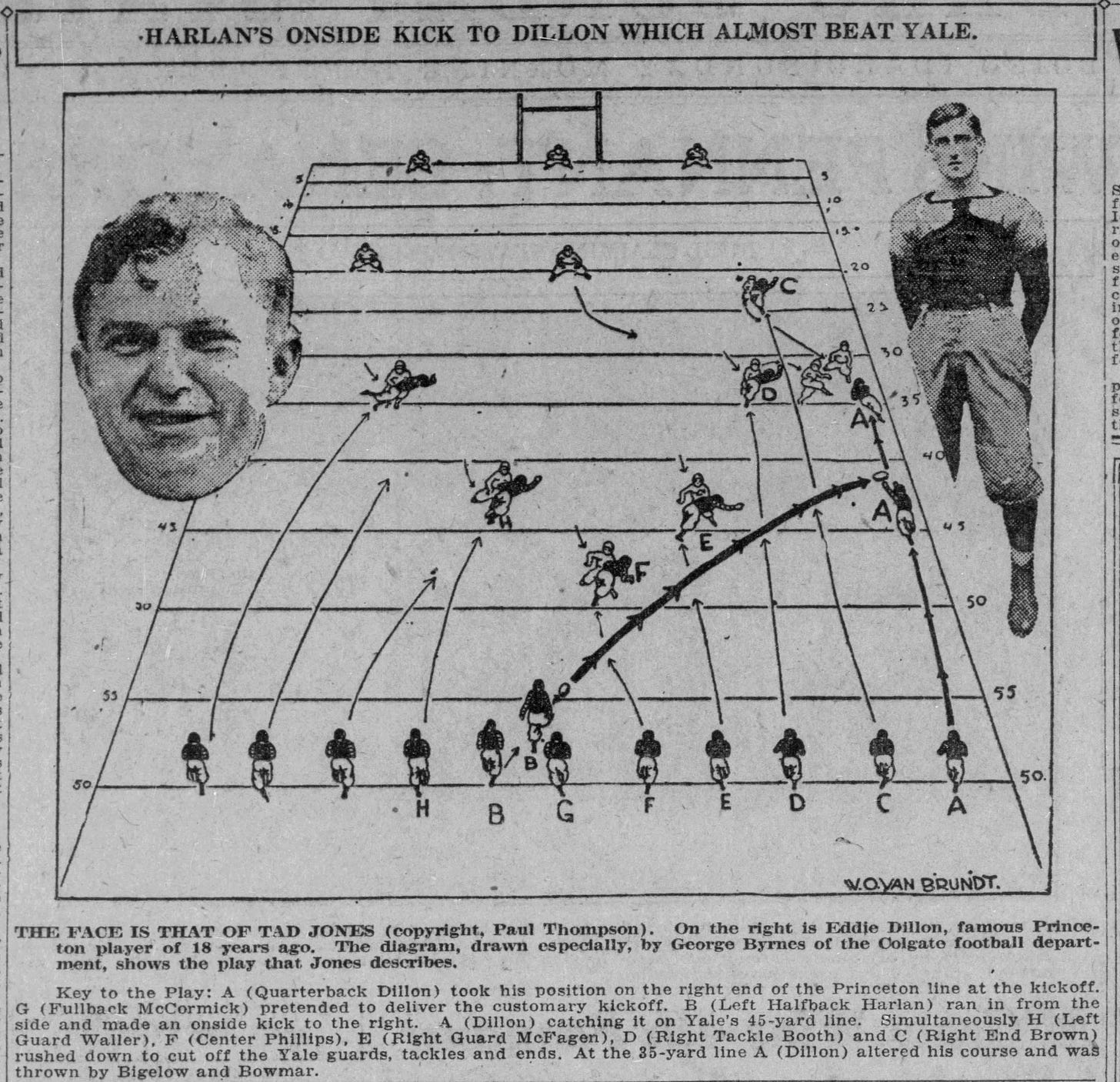

Another reason not to onside kick was the limited substitution rules of the day. The starters already devoted practice time to offense and defense, so only risk-takers like Indiana's Harlan Page bothered with that. He and a few others (e.g., Furman, Oregon) in the 1920s shifted the kicker to the far right and either kicked downfield into the right corner or onside kicked on a diagonal to the left.

Oddest of all is that teams seldom onside kicked in late-game situations, now considered coaching malpractice when teams fail to onside kick,

One benefit of onside kicking in the old days is that the kicking team could advance the ball on a recovered onside kick through the 1948 season. After that, the ball was dead upon the kicking team recovering.

A 1932 rule to limit receiving teams from dropping back and forming wedges on the return required teams to position at least five players between ten and fifteen yards from the spot of the kick. That rule made the conventional onside kick more difficult but opened up the space behind the forward wall. Gus Welch, Jim Thorpe's quarterback at Carlisle, responded to the new rule by having his American University team line up for the kickoff as usual. Then, they lateraled the ball to one another until they spotted a hole in the return team's alignment, at which point they dropkicked the ball into that spot.

Through the mid-1950s, teams continued showing reluctance to onside kick, but the advance of offenses and the willingness to take risks appear to have turned the tide, leading to more onside kicks, especially when teams were down late in games. Finally, specialist kickers and special teams coaches further pushed the issue, so onside kicks are now part of every team's arsenal.

Postscript:

A reader, Carter Claiborne, sent several images of onside kicks outlined in Guy S. Lowman's Practical Football - How To Teach It (1927). Here’s his description of an onside kick that remains popular today.

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to buy one of my books or otherwise support the site.