Today's Tidbit... Col. Roy C. Baker And The Flip-Style Down Marker

While I enjoy learning and writing about football innovations that Amos Alonzo Stagg, John Heisman, or even Rich Rodriguez sent our way, my favorite stories are those in which an everyday person takes a different approach and develops something that impacts the football world. This is one of those stories, and even better, it crossed my path because a family member of the innovator contacted me looking for information about his contribution, but I had nothing to offer. I had never heard of him.

His name was Roy C. Baker or, more accurately, Colonel Roy C. Baker. Does that name ring a bell? Probably not, but if you were a sentient football fan before 1995 and even later at football's lower levels, you witnessed his invention in use on nearly every football field. And yet, few have heard of him.

The NFL recently acknowledged that it is testing a technology-based approach to determining whether the football crossed the line to gain to earn the offense a first down. Football first measured for first downs in 1882, when Walter Camp convinced others that teams should gain five yards in four downs or give up the ball. To help referees judge whether a team gained five yards, they added parallel lines on the field spaced five yards apart. It took another dozen years before clever folks with the Crescent Club of Brooklyn connected two poles with a five-foot length of chain or cord, inventing football chains. The next year, the rules required the home team to provide two assistants to man the chains for the linesman, who came to be called the head linesman.

Over the next few decades, there were many other measurement inventions, including various surveying-like tools to add precision to the first down-measuring process, but few had any impact. In 1916, the rules committee considered adding stripes to the field every two yards to help the measurement process, but cooler heads prevailed.

One change that became widespread was the addition of a third assistant linesman who held the down box or down marker, marking the spot where plays started. Early down boxes were simple boxes attached to a pole with a 1, 2, 3, or 4 on each of the box’s four sides. They stood waist-high early on before growing taller so spectators and the press could see them.

The first down boxes suffered from a fundamentally poor design. The side of the box displaying the current down faced the playing field. It allowed the players and officials near the line of scrimmage to see the number, but everyone in the stands behind the assistant linesmen and many to the sides could not see the number facing the field. They saw the number on the opposite side of the box or the numbers on its sides. It was a problem begging for a better solution, yet the begging lasted for decades.

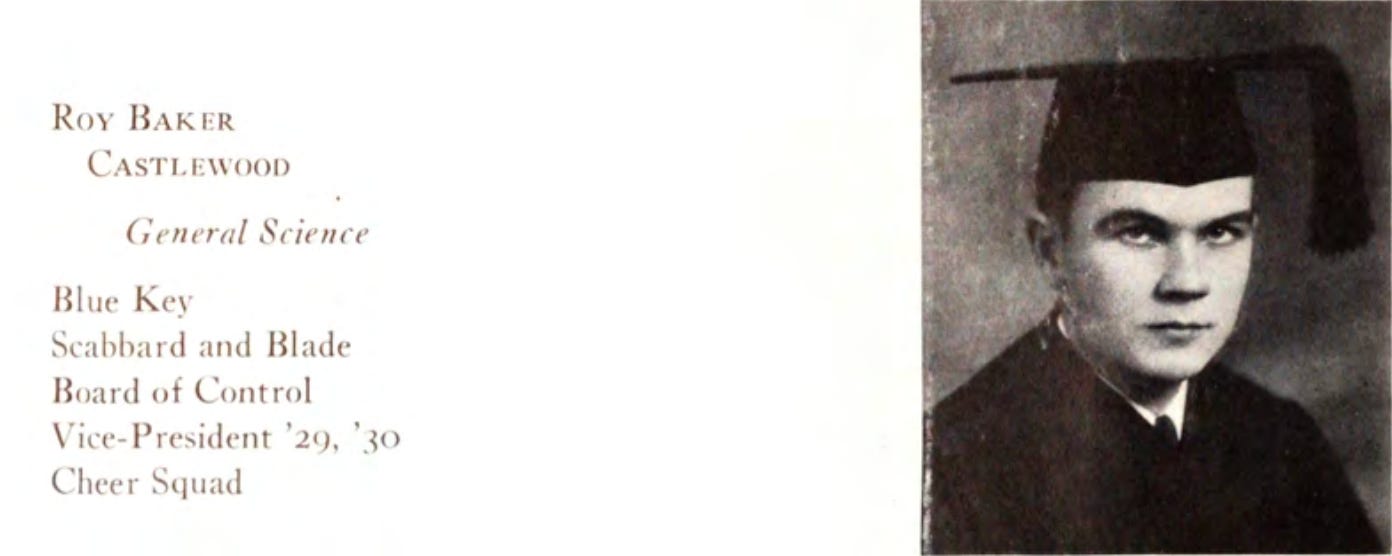

Remember Roy C. Baker? Census records tell us he was born Leroy C. Baker, one of four boys and a girl who grew up on their parent's farm outside Castleton, South Dakota. Baker left the farm to attend South Dakota State, where he earned a General Science degree and was a cheerleader, class officer, and ROTC cadet.

Graduating in 1932, Baker taught high school science in Britton, South Dakota, for a few years before moving to Johnson County High in Buffalo, Wyoming, where he coached football and basketball. He inherited a less-than-stellar athletic program at Johnson County but soon built winning teams, especially on the basketball court.

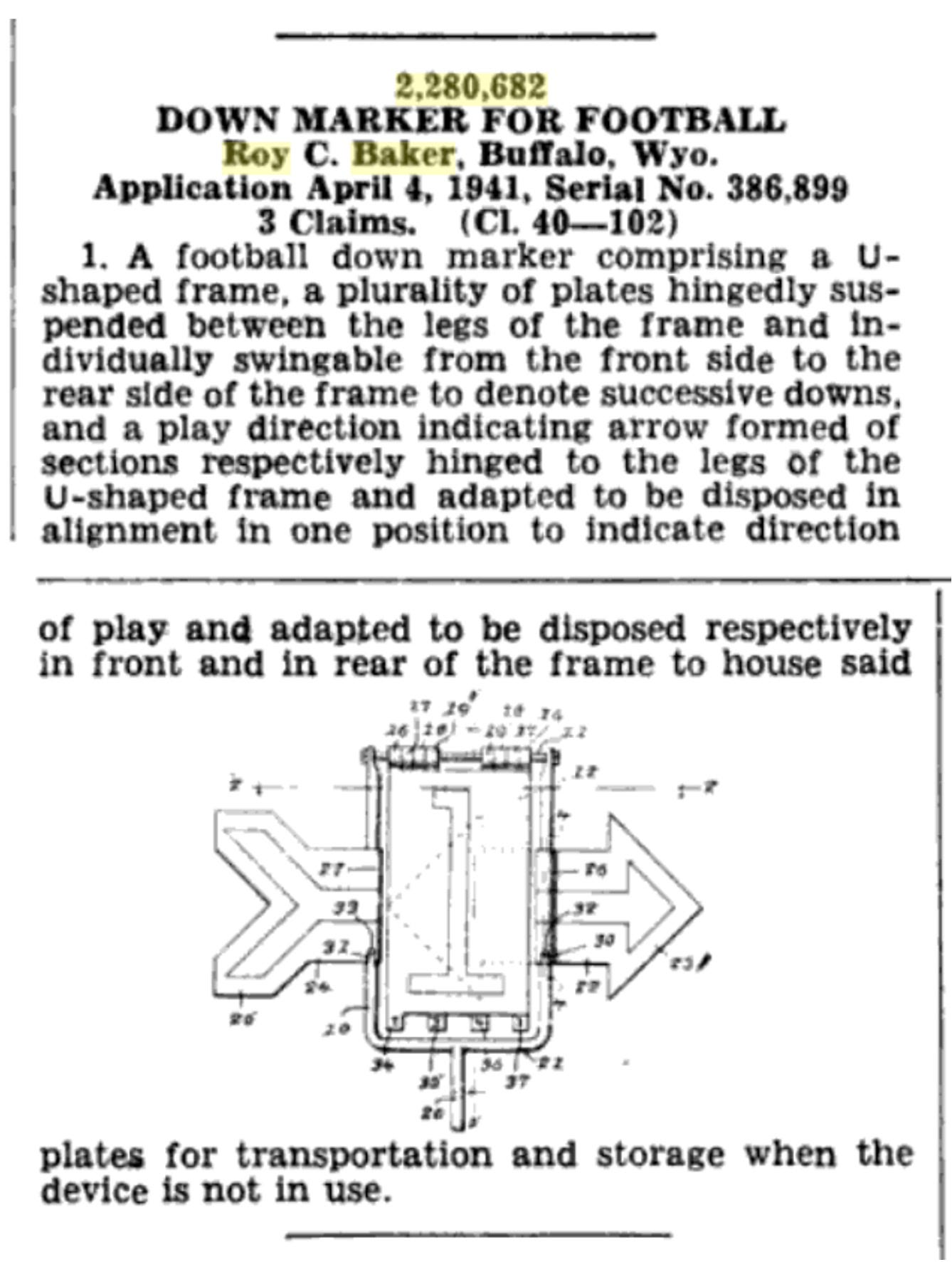

Late in the 1930s, Baker had an idea for a new type of down marker elegant in its simplicity and obvious to anyone who saw one, but he was the first to think of it. Baker used sheets of paper to confirm the logic of his design before heading to a sheet metal shop to create a working version of the flip-style down marker. Baker's down marker had four metal sheets suspended on rings from a U-shaped frame. Each metal sheet had a number on each side, and they were sequenced, so the first sheet had a 1 on the side facing the field and a 2 on the other side. The next sheet had a 2 facing the field and a 3 on the reverse, then a 3 and 4 combination, and a 4 and 1 combination. With that sequence, the number facing the field matched the number facing the crowd, so everyone saw the same number. It was brilliant in its simplicity.

Baker sold his markers to schools in Wyoming and elsewhere, including one to the University of Nebraska.

Baker applied for a patent in April 1941 and received it in April 1942. However, as an Army Reserve officer when America entered WWII, he reported for active duty three weeks before the patent approval came through.

Baker served in Europe during WWII, and after returning from the Occupation Army in Germany, he found that others had taken his idea and were selling flip-style down markers. Baker challenged the companies about the patent violation, but they flippantly told him to sue them. His discussions with lawyers suggested he might spend more money contesting the patent violations than he would gain in penalties, so he gave up his challenge and watched his idea become the dominant down marker design in the football world. Other than those he sold pre-war, he never received another penny for his invention.

Instead, Baker remained in the Army, primarily working in the quartermaster arena, and achieved colonel rank by 1950 or 1951. He also served in Korea from 1956 to 1958, retiring in 1965.

Baker made it back to Buffalo, Wyoming, in 1955 for a reunion of the football teams he had coached and, in retirement, worked as an usher at Washington Redskins games. He ushered during the 1983 season when a Washington Post story profiled him and his invention in the run-up to the Redskins' loss in Super Bowl XVIII. Four years later, the louvered Dial-A-Down hit the market. It has since replaced Baker's flip-style down markers as the dominant tool of the assistant linesmen trade.

Baker passed away in August 1999, not long after his 90th birthday. He is buried in Arlington Cemetery, having never received acclaim or the financial benefit of an innovation that dominated football sidelines for 50 years.

The football world owes you a debt, Colonel Roy C. Baker, and we salute you!

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to buy one of my books or otherwise support the site.

Thank you Mr. Baker. You made life a lot easier on the field for officating commumications with the teams and fans, and to make it more of a fair and level playing field.

Also thnak you Mr brown for the great research and the Baker relative that was looking for answers so that this hidden gem of football history could be remembered and preserved!

So simple even I was able to operate it for youth football games 😄

The digital ones UFL is using with down and distance are cool. Assume it received a signal from an operator or the scoreboard