Today's Tidbit... Football's Biggest Cover Up

The following are words I never thought I'd write: this story concerns the early days of tarpaulins covering football fields. Like many stories you read here, I came across it while reviewing an article about another topic (coaching clinics in the 1920s) when I spotted a neighboring article with an interesting headline, in this case:

I initially assumed the article concerned the sideline gear worn on rainy or cold days, but a quick scan revealed the raincoat in question was for the field, not players. So, while I had not intended to write an article about tarpaulins, this was a story I had to cover.

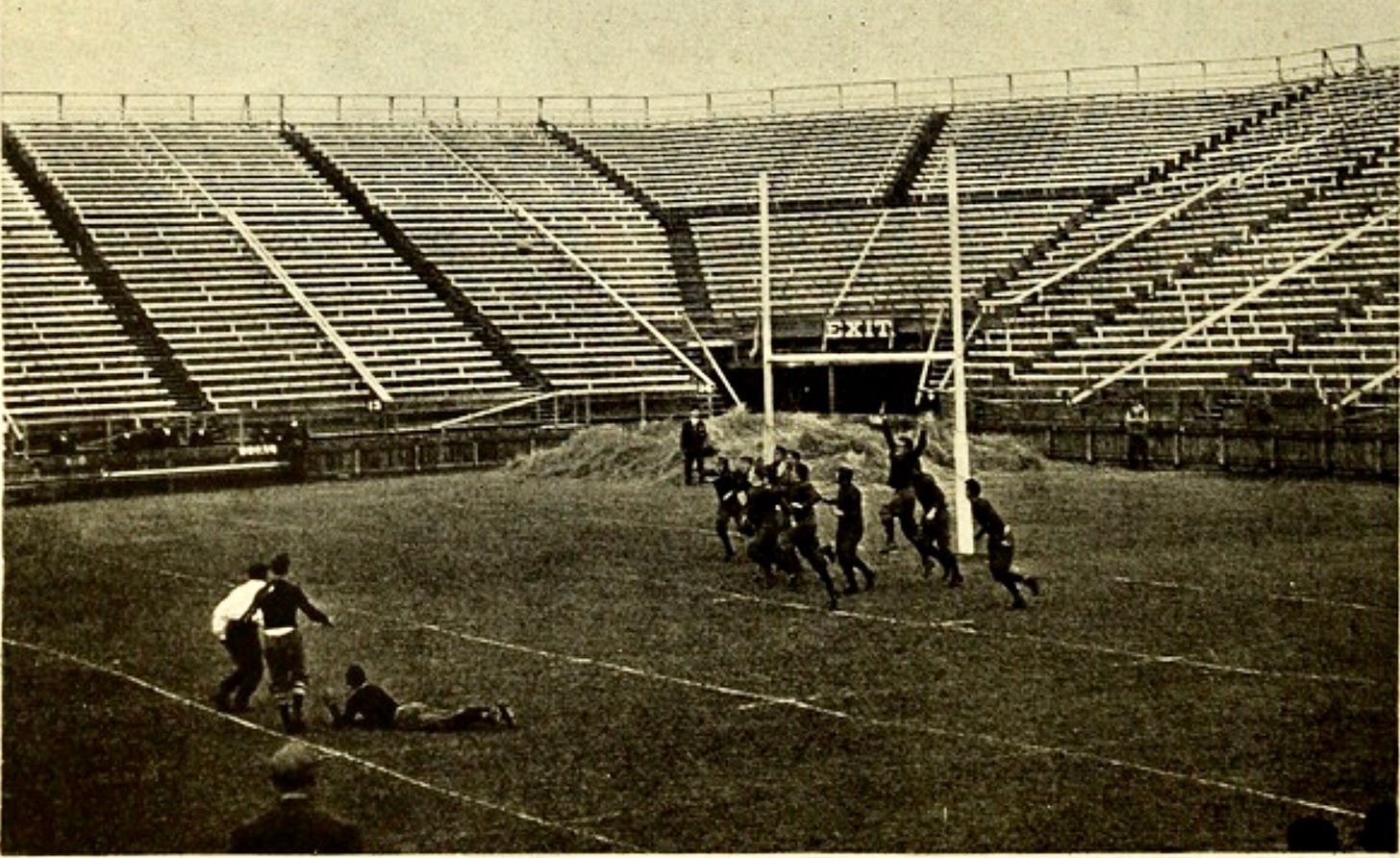

An earlier story about the wretched field conditions of the past discussed teams and stadium personnel spreading sawdust on fields to absorb moisture and hay to protect against frost.

Spreading sawdust and hay worked to some extent. Still, they were not as effective as desired, so the stadium people considered alternatives they found on tennis courts and baseball infield, which were covered by tarpaulins when expecting rain. (For vocabulary geeks, a pall is a large piece of cloth often draped over coffins, which is why we have pallbearers. A tarpaulin is a large pall covered in tar to protect cargo and other items, originally on sailing ships.) Although the value of tarpaulins for football fields seemed clear, a gridiron has four times the surface area of the tarps covering baseball infields, so they were more expensive and needed larger work crews to put on and take off. As a result, football did not use tarps until the stadium building boom of the 1920s provided stadiums holding large numbers of ticket-buying fans. So it was that the first football tarp rolled out in Illinois' Memorial Stadium, which opened in time for Red Grange's sophomore season in 1923. Although the Illini powers-that-be realized the fans preferred watching Grange play on dry fields rather than mud bowls, they did not buy a tarp until Grange left, rolling out a rubberized canvas tarp made by DuPont for the 1926 season.

Missouri added one later in the 1926 season, and Cal had one in 1931 when the students hired to roll it onto the field refused to do so after realizing a dry field would help USC, their upcoming opponent. Since the rain began falling before Cal could hire a non-student crew to roll out the tarp, the field got wet, though USC won 6-0 anyway.

Motivated by the sloppy conditions of the 1930 Duke game, UNC added one of the first football tarps in the South in 1933. Tulsa, Ohio State, Wisconsin, Birmingham's Legion Field, and Harvard added tarps in the 1930s, as did Massillon Washington High School during Paul Brown's tenure as coach.

In some situations, grounds crews used a combination of tarps and hay to keep fields dry and warmish. That was the case in 1961 when Green Bay's City Stadium, now Lambeau Field, was covered with a tarp and a foot of hay to protect the turf before the NFL championship game. The hay and tarp were removed from the field the morning of the game, which the Packers won over the Giants 37-0.

Football fields and tarpaulins have had an on-again, off-again relationship since then. Although they became a regular feature on college and pro fields, they never gained the iconic status enjoyed in baseball, where they are rolled on and off for rain delays. Improved drainage systems, heated fields, indoor stadiums, and artificial turf now limit their use in football. And unlike baseball, football games continue whether it rains or not, so fans often do not notice the tarps along the sideline waiting for the opportunity to shield the fields from Mother Nature's ravages.

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to buy one of my books or otherwise support the site.