Today's Tidbit... Inventing the Option/RPO in 1929

There's a first time for everything, and if you want to figure out the first time something occurred, you have to define that something before claiming to find its first instance. Once you define something and the earliest instance of it happening, you should remain open to finding an earlier example because it might just be sitting out there waiting for someone to find it.

Some think the first instance of something occurs when it first receives its name. But that approach can be problematic for several reasons. The meaning of some terms changes over time, so a play that was once known as the flea flicker can and did become the hook and lateral. What we now call the flea flicker is an entirely different play from the original.

Likewise, the first use of a term for something is not necessarily its starting point. Football insiders did not begin using "lateral" until 1914, and "handoff" meant stiff arm until the early 1940s, at which point it took on its current meaning. Yet, no reasonable person, not even an Iowa fan, would argue that laterals and handoffs did not exist before people used those terms.

Like many other footballisms, identifying the invention of the option or option play requires defining the term behaviorally and then finding the first instance to which that definition applies. Let's see how that works for the option.

"Option" has had multiple meanings in football. There have been or are halfback options, option routes, and option blocking, each of which suggests players making a decision during a play. However, the core use of option refers to plays in which the offense designates a player on defense and leaves him unblocked on the play. The offensive player with the ball watches the unblocked player to make a decision. If the defender does A, the offensive player does B. If the defender does C, the offensive player does D.

Many option running plays give the offensive player the opportunity to keep, give, or pitch the ball based on reading the unblocked player. In the case of RPOs, he may pass the ball. Either way, the specific actions of the unblocked defender lead to specific actions by the offensive player.

Leaving a designated player unblocked and reacting to that player is the basis of option plays. Offensive players responding to a defender's actions is necessary but insufficient since that definition applies to nearly every action on the field. As far back as 1906, teams ran plays with the quarterback passing the ball to a nearby teammate when any defender approached the quarterback intending to tackle him. The decision was akin to a rugby sweep when the ball carrier tossed the ball to a teammate shortly before being tackled. The ball carrier got rid of the ball whenever any defender approached him, not a specific defender. Also, the teammate receiving the ball was not predetermined.

Applying the designated unblocked defender rule, I had argued in the past that football's first option play came in 1941 when Missouri's Don Faurot revealed his Split T offense.

The Split T used the T formation with wider than normal line splits. The main series had a predetermined dive or dive fake. Then, the quarterback proceeded parallel to the line of scrimmage, reading the defensive end to decide whether to keep or pitch the ball to the trailing halfback. The trailing halfback might have a pass option as well.

Familiarity with Split T contributed to the thinking behind the Veer, Wishbone, and later the Read Option, but was there a predecessor to the Split T? Until recently, I would have said there was not, and then one popped up.

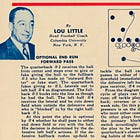

Sol Metzger, whose syndicated column documented interesting play designs for years, outlined a 1929 play Pop Warner ran from Stanford's Double Wing. The story ran the morning of their game with West Coast Army and described a play fans could expect to see that day. (West Coast Army was an all-star team comprised of the West Coast's top active duty soldiers. They played college, athletic club, and other military teams.) Previous West Coast Army content includes the following:

As drawn up, Warner ran his play from the Double Wing with the fullback receiving the direct snap. The fullback then moved to his right, reading the left defensive end. If the defensive end attacked the fullback, he passed it to the backside wing, crossing the formation. If the defensive end followed the backside wing, the fullback cut inside and ran the ball.

As Metzger wrote:

It starts as a run and winds up as a pass, and you can't tell which it will be.

...No one is assigned to take the opposing left end, although his territory is to be attacked. The idea here is to remove this vulnerable man without wasting an interferer on him. That gives you an extra man to take out the other defensive players.

By the definition of the option presented earlier, this Pop Warner play is an option, even an RPO, making it the earliest option or RPO I have come across.

Interestingly, the play should look familiar to anyone watching college and NFL games since it is like the Shovel Pass Option we regularly see. Compare the examples below with Pop Warner's play.

In Warner's version, the pass goes to the backside wing, outside, or closer to the sideline than the shovel-passing fullback. The difference in the design versus today likely reflects most teams running 7-2 or 6-3 defenses in Warner's day, so more defenders were in the box, making the outside more attractive. Also, the football field did not have hash marks then, so Warner's RPO would have been a good call when a play began close to one sideline or the other.

Of course, since Pop Warner figured out this gem by 1929, one has to wonder why it and other option plays did not catch on for the next decade. I have not begun to answer that question but feel free to offer suggestions below. Nevertheless, this RPO it is an instance of a play design that had a brief moment, disappeared, and reemerged 80 or 90 years later.

Here's Sol Metzger's full article.

Click Support Football Archaeology for options to support this site beyond a free subscription.

My father played high school football from 1929 to '32. He used to tell me that most of the coaches seemed to care only about the smashmouth aspects of the game...three yards and a cloud of dust. Plus, they were obsessed with field position. Keep punting and wait for a break. Nothing radical.