Today’s Tidbit... Restricting Ineligible Receivers

Football is a game of inches, with winners sometimes marching down the field on long, 15+ play drives. Those drives may seem slow, but a score is a score and a win is a win.

Football’s rules sometimes change at a similar grinding pace. Rather than making quick-strike changes, the Rules Committee often moves in a series of small steps that, together, create notable changes in how we play and think about the game. An example of that progression concerns the role and restrictions on ineligible receivers.

Like rugby, early football had specialized player roles, but everyone was more of a generalist in early football. Everyone played offense and defense, and some kicked the ball. Linemen commonly ran with the ball, with end and tackle around plays in every playbook.

Players became more specialized over time, and the forward pass was a key contributor, especially as the rules increasingly restricted ineligible receivers while easing restrictions on the passing game more generally. The fact that some players could catch the ball while others could not was one restriction, as was the 1906 rule that made forward passes touching ineligible receivers into turnovers at the spot of the foul.

On the other hand, the early forward passing game placed no constraints on where ineligible receivers could go on the field and what they could do when they got there, other than touch the ball. Since the forward pass entered a football world that allowed players to block or tackle opponents while the ball was handed, lateraled, or passed backwards, the rule makers applied similar thinking to the forward pass. The 1906 rules allowed ineligible receivers to go downfield and block opponents before, during, and after the ball was in flight.

There were no defensive or offensive pass-interference rules in 1906 and 1907, so a common passing play design had teammates encircle the receiver and block defenders while the ball was in the air. The 1908 rules introduced pass interference, which banned contact with a potential receiver or defender while the ball was in the air, except when making a bona fide attempt to catch the ball.

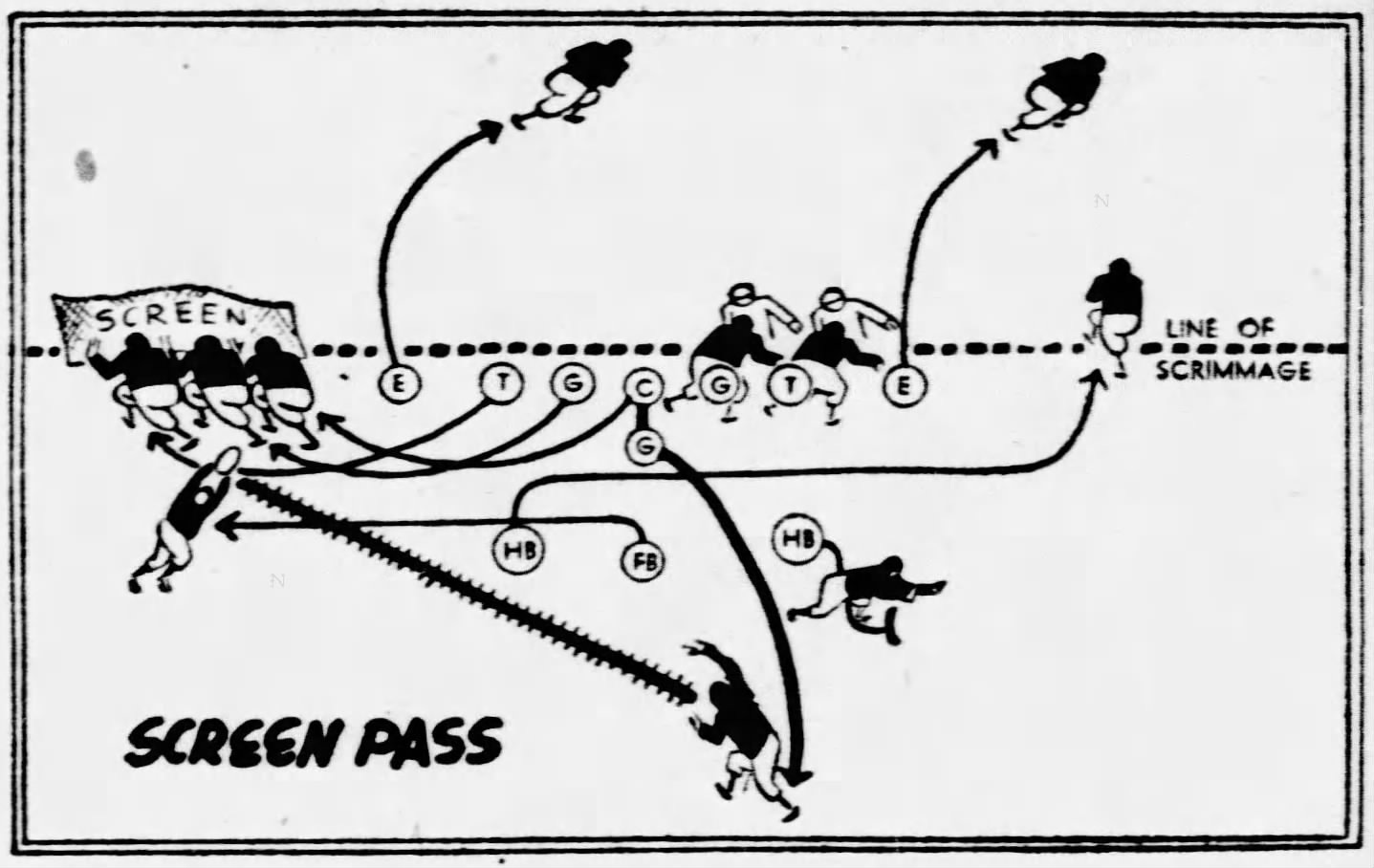

With the introduction of the pass interference rules, “the circle the wagons” play morphed into the screen pass, leading to questions about what constituted interference. For the next 15 years, football tried to restrict ineligible receivers without clearly defining what was allowed and what was not. Those questions increased in prominence in the early 1920s, when Ohio State and Notre Dame became powers while making extensive use of screen passes.

The first attempt at defining what not to do came in 1925, with a rule stating that:

“... players ineligible to receive the pass must keep out of the way of the side which did not make the pass; otherwise they will be liable to penalty for interfering with the defensive side’s opportunity to reach the ball.”

While the rule was a step in the right direction, the imprecision of “keep out of the way” prompted calls for further clarification. In addition, the rules did not restrict offensive players from doing dastardly deeds downfield before the pass was thrown, which led to a 1928 rule prohibiting offensive players who crossed the line of scrimmage from interfering with the defense until a receiver caught the forward pass.

The 1930 rule makers got really tough by changing the rule’s wording to keep ineligible receivers from interfering “in any way,” but the revised rule left much open to interpretation.

The next big change came in 1936, when the rulemakers effectively eliminated the screen pass by making it illegal for an ineligible receiver to go beyond the spot where a receiver caught a pass. Other language banned ineligible receivers from venturing into the part of the field where the pass was thrown.

A 1938 rule took the restriction a step further by prohibiting ineligible receivers from crossing the line of scrimmage before the ball was thrown. Since offenses no longer needed linemen who could run downfield ahead of pass receivers, those players no longer needed to be as mobile as in the past, contributing to the movement toward vastly different body types by position that we know today.

Ineligible receivers caught a break in 1940 thanks to Dana X. Bible, then coach at Texas and a Rules Committee member. Shovel passes had come into the game in the early 1930s, and ineligible receivers were sometimes inadvertently struck by them behind the line of scrimmage, resulting in a turnover per the 1906 rule. Bible campaigned for and gained approval of a rule that made ineligible receivers able to touch forward passes behind the line of scrimmage.

The 1949 rulemakers restricted ineligible receivers from crossing the line of scrimmage until a forward pass touched a receiver, rather than from the time it was thrown, before returning to the old rule in 1958.

The final big change came in 1977 and more or less brought college football’s ineligible receiver rules to where they are today. The game’s officials had generally been confident in their rulings on ineligible receivers downfield on standard passing plays (e.g., dropbacks, bootlegs). However, they struggled to interpret those rules in the world of option football. The challenge wasn’t passing from the option; the running plays were problematic.

Veer and Wishbone offenses of the time had their offensive tackles, guards, and centers fire off the ball, blocking or optioning a man, so they often ended up downfield. However, since the quarterback might pitch the down-the-line option backward, parallel to the line, or forward, it became difficult for officials to monitor the downfield blocking rule when the pitch travelled forward, which was a forward pass, even if the pitch and catch occurred behind the line of scrimmage.

To remedy the situation, the officials suggested allowing downfield blocking on all passes caught behind the line of scrimmage. Adopted for the 1977 season, the rule made option plays easier to call, and coaches latched onto the rule by implementing screen passes caught behind the line. So, despite the disappearance of down-the-line option plays outside the service academies, the rules continue to allow downfield blocking in that situation, which explains the greater use of screen passes in college football than in the NFL, which does not have the behind-the-line-of-scrimmage rule.

The history of the rules covering the parts of the field that ineligible receivers may venture into and what they can do upon arriving is an example of the slow, meandering path rules sometimes take. It also points to how game conditions in one period can drive new rules, and, even as those conditions change, the rules often remain in place because people take advantage of them for other purposes. And in the case of ineligible receivers, not only have these rules changed the game, they have helped reshape the players themselves.

You might also want to check out an article published today on The Triibe that covers the 1938 game between the Chicago Bears and the Negro All-Stars, which took place when the NFL banned Black athletes.

I’m quoted a few times based on my writing about the game a few years ago.

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to donate a couple of bucks, buy one of my books, or otherwise support the site.