Today's Tidbit... Scoring the 1939 Army-Navy Game

Buying a scorecard at a major league park and tracking each pitch or batter is a rite of passage in American sports, with some fans scoring every game they attend. A similar tradition never developed in football. I'm guessing that was the case for several reasons. Early football was a less discrete game than it is now in that teams quickly lined up after a man was downed and ran the next play, so the game flow was more continuous.

Football players also did not consistently wear numbers front and back until the 1930s, which is when the NFL and NCAA first tracked game statistics consistently. Player numbering allowed statistics to be more easily tied to specific runners, passers, and receivers, but fans could have tracked the progress of games at a team level. The game diagram below shows the ball's movement in the 1896 Cal-Stanford game, a system newspaper reporters used for decades to track the game and was reproduced in their game coverage the next day.

Periodic attempts were made to encourage fans to chart plays, including the 1926 Chicago Daily News Football Visualizer, which I wrote about previously.

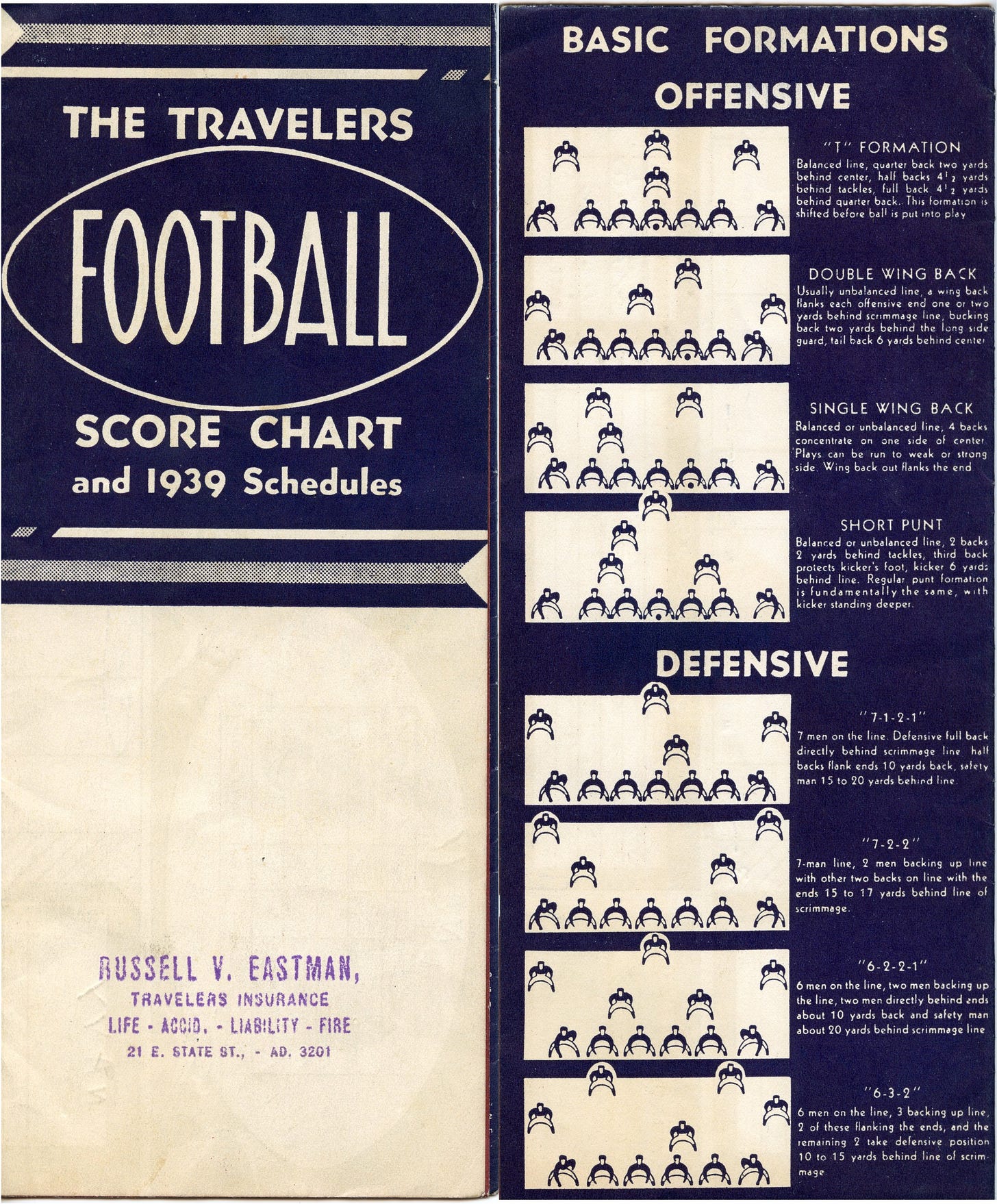

Still, I don't recall coming across an example of a fan scoring a game until I found a 1939 Travelers Insurance advertising premium that included formations, schedules, and a blank "Score Chart" to track an upcoming game, though it wasn't blank by the time I found it.

Our unknown fan might have scored the game while listening to the radio since it was broadcast everywhere, including multiple stations in many cities.

FDR and Eleanor Roosevelt did not attend, but two of their sons made it. So did the Secretary of War, the Acting Secretary of the Navy, other cabinet members, ambassadors, and Joint Chief of Staff George Marshall.

Lesser-known celebrities attended as well, including Mr. and Mrs. Alfred Bergner, German immigrants, and Silvio Stella, an Italian immigrant, each of whom had settled in Kankakee, Illinois, after coming to America. The Bergners' son was Navy's captain and Stella's son was Army's.

Of course, one would hope our intrepid scorer was among the 102,000 that jammed Philadelphia's Municipal Stadium that misty afternoon to watch the game. The mist turned to a drizzle at halftime, and fog rolled in by the fourth quarter, making it difficult for one sideline to see the other.

The lack of water damage on the chart and the fact the fourth-quarter plays were charted properly suggests our scorer was a radio listener. Besides, the Travelers Insurance agent who gave away the advertising premium was in Columbus, Ohio.

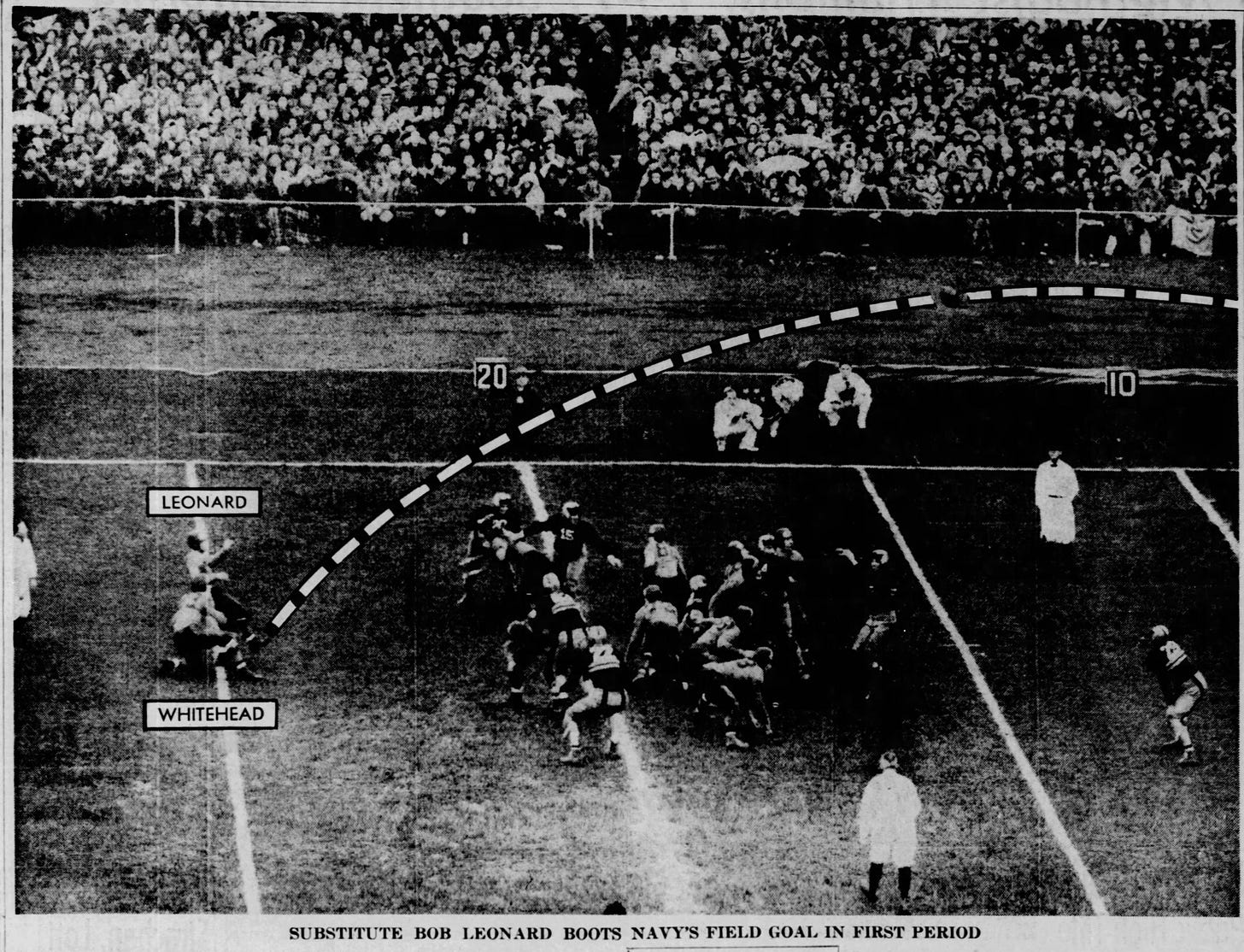

The first quarter chart, which shows Navy moving left to right, indicates the Middies pushed the ball down the field before Bob Leonard booted a 17-yard field goal with 7 minutes left to give Navy a 3-0 lead.

Navy's Richard Shafer ran for a 22-yard touchdown on the first play of the fourth quarter, though our scorer penciled in a longer TD run several plays into the final stanza. Either way, Leonard kicked the extra point to give Navy a 10-0 lead, which remained unchanged until the final gun.

Notably, the 1939 Army-Navy game—their fortieth meeting—was only the third time Army lost to Navy by double-digit points. Army lost to Navy 24-0 in 1890 in their first game and by a 10-0 score in 1906.

Army finished the season 3-4-2, while Navy ended 3-5-1, leading alums on both sides to raise concerns about their school's coaching philosophies. For decades, both schools were coached by alums, former players who served as regular Army and Navy officers before being assigned to coach at the academy, often after being away from college football for a decade or more. Football's increased sophistication made that approach more difficult than in the past, and at different points in the 1950s, both schools hired football professionals to coach their teams.

Click here for options on how to support this site beyond a free subscription.

I bought a book back in 1972 that charted every game of the '71 NFL season. Here's an example (the Super Bowl): https://www.dropbox.com/scl/fi/jjiaabwgq5xpsihhrai0v/SuperBowlVI.pdf?rlkey=tnezwvvtpf0wtgtjr93duwbvg&st=oaawsbsm&dl=1. It's pretty easy to follow once you get the hang of it. Runs are solid lines, passes are dashed lines. The number is the ball carrier or receiver.

Let me know if you want to see the whole book.