Today's Tidbit... The House Of The Setting Sun

An avid reader of Football Archaeology who is researching early pro football sent the following question this morning:

I have been running into almost every [team name] game in 1903 having the first half being longer than the second half. For example, the 1st half will be 25 minutes long and the second half is 20 minutes.

Since they were playing by college rules in 1903, do you have a good explanation as to why?

I've previously covered this topic in bits and pieces, so I'll use this Tidbit to provide a consolidated answer. In addition, answering the question allows me to retell one of my favorite stories of how outside events led to changes in football's rules.

At some point in my many years of schooling (I was not held back, thank you), I learned the difference between de jure and de facto. De jure describes how things should be according to the law, while de facto concerns how things occur in practice. Applying those concepts to football, the rulebook prescribes how teams should play football, but teams do not always follow the rules in practice or games.

The de jure and de facto distinction was critical when the game began because football had only 61 rules. The rules did not prescribe many game elements, yet teams could play football based on tradition, and players gained an understanding of informal "rules" along the way. In effect, they understood the game's culture.

Notably, the IFA rules of 1876 did not specify the length of games, though teams played two forty-five-minute innings or halves by tradition. The halves were reduced to thirty-five minutes in 1894 and thirty minutes in 1906 before shifting to four fifteen-minute quarters in 1910. Other than the NCAA's addition of overtime in the 1970s, the game's length has held steady for 117 or 113 years, depending on how you define it.

That covers the de jure side of things. How about the de facto?

Early football effectively had a running clock. Time might be called for an injury and later to kickoff and for goals after touchdowns, but it did not stop for incompletions because there was no passing game. The clock continued running when the ball went out of bounds because the ball remained live. Early on, the game did not even have first downs; neither did they stop the clock once first downs arrived. The combination of the nature of play and the running clock resulted in games finishing in under two hours, including the ten-minute break at halftime.

So, what was different in 1903 that caused them to cut the second half short? Without knowing the specifics of the team in question, the general difference was that games started later and, lacking artificial lighting, they had to finish games before sunset.

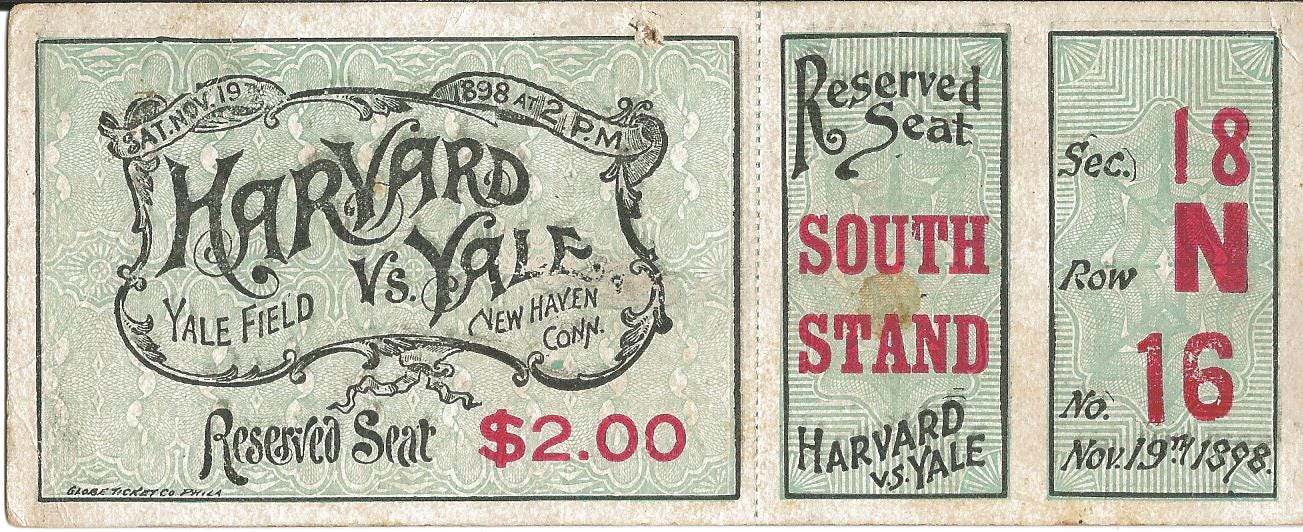

Football games started in the middle of the afternoon because they had always done so, mainly due to the transportation challenges of the time. The soccer-style games played by Rutgers and Princeton in 1869 began at 3:00 p.m. The Harvard-Yale concessionary game of 1875 kicked off at 2:45 p.m., and so on. Games started at 2:00 p.m. and 2:30 p.m. because that was the norm and because the timing allowed teams and fans from within the region to get to the games without an overnight stay preceding the game.

Also, in an age when a high percentage of the population had farm chores, earned wages six days per week, and went to church on Sunday morning, starting games later than we might today made sense.

Of course, things do not always go as planned. Trains derailed or experienced delays for other reasons. Besides the unscheduled problems, home or visiting team locations that were not well connected by rail meant the teams could not play the full sixty minutes and expect the visiting team to get home that night. There were also occasional blowouts that caused the shortening of games. Importantly, no adjustment to the length of halves or quarters was allowed under the game's rules, but the owners or captains agreed to the adjustments anyway.

All that leads to a favorite story of how outside forces led to changes in football's rules. Over several decades, football began stopping the clock more often during play. Captains gained the ability to call timeout several times per half, and incomplete forward passes led to clock stoppages as well, so games began taking longer despite the reduced clock times.

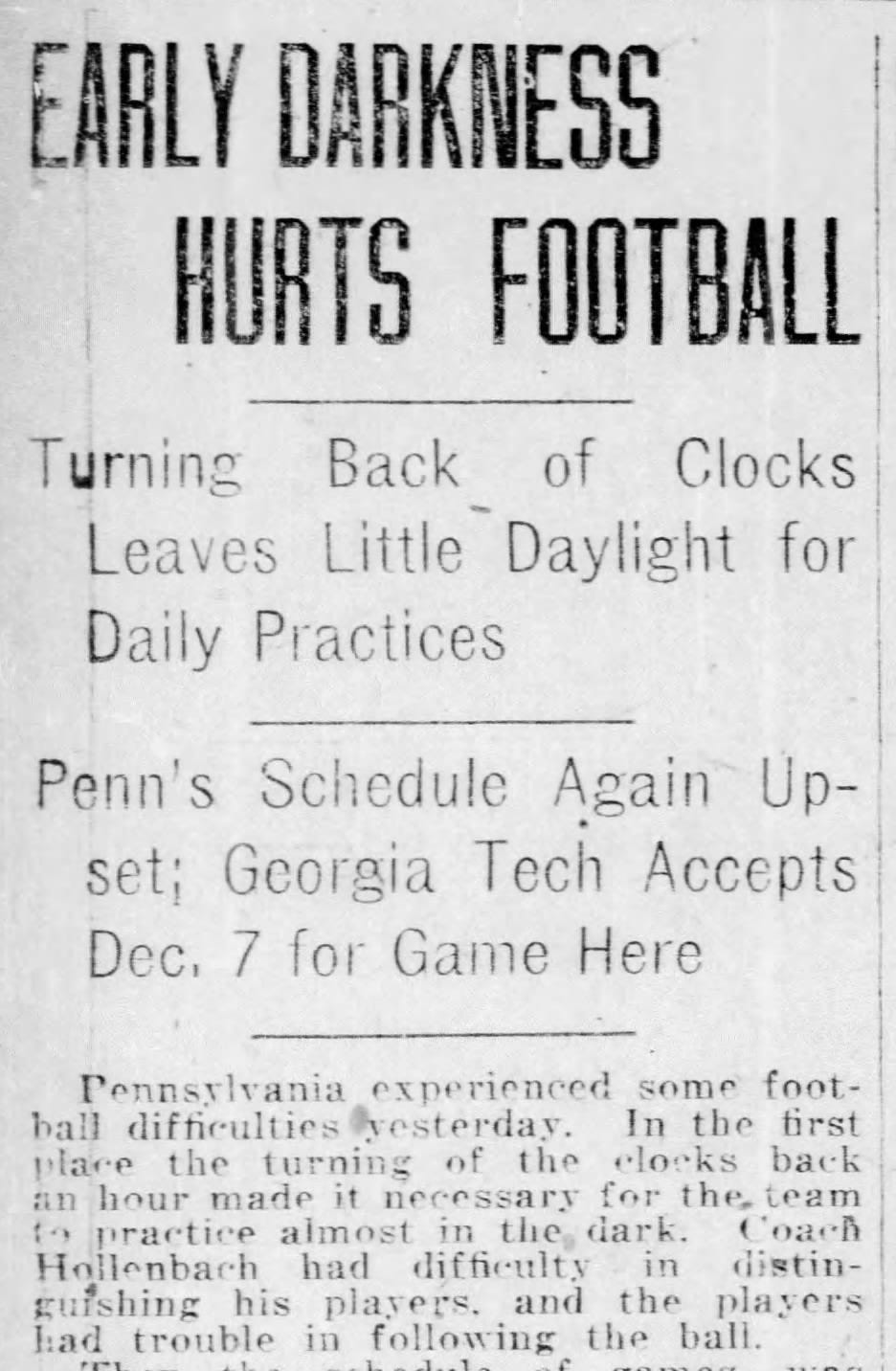

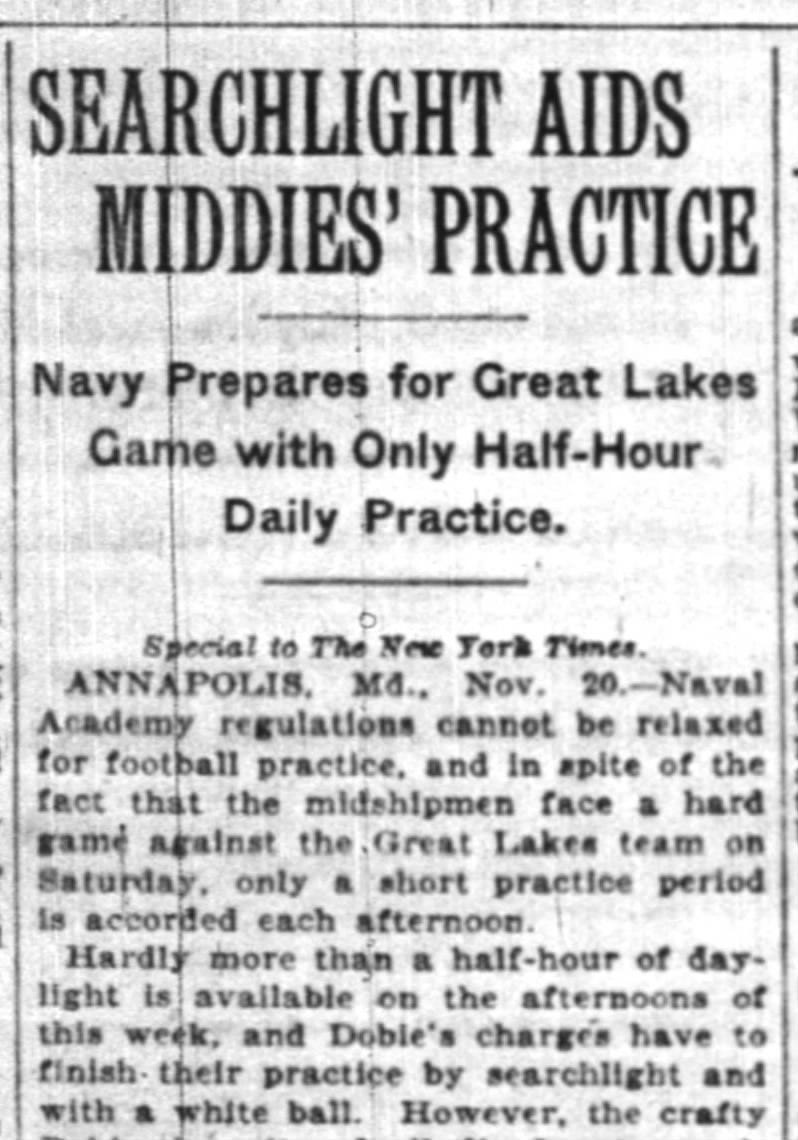

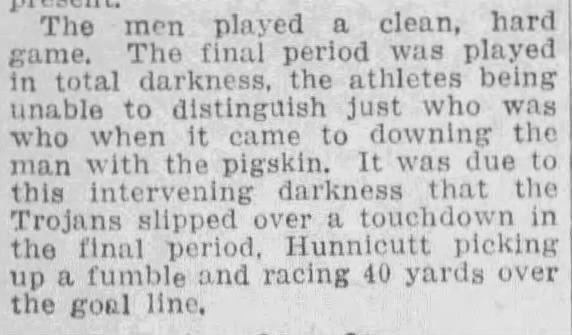

Then, the U.S. entered WWI in 1917, leading Congress to enact Daylight Saving Time in 1918. While the end of Daylight Saving Time and “falling back” in October had less impact on games and practice for southern teams and those sitting near the western border of their time zone, teams in the Northeast, Chicago, and similar locations suddenly found themselves dealing with darkness an hour earlier than in the past. That meant teams needed to start games earlier, install lighting, play with a white ball, or cut games short. Since teams began cutting games short more often, spurring disagreements, a 1922 rule change allowing referees to confer with the team captains at halftime to shorten the second half if needed.

Starting games earlier to satisfy the television gods, effective stadium lighting, vastly improved transportation systems, and budgets allowing teams to stay in hotels the night before games have changed the dynamic, but none of those elements were in place for the football games of 1903.

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to buy one of my books or otherwise support the site.

UNC had several late kickoffs before 1927. I found several 4:15 PM kickoffs with the last one being 1903. The last 4 PM kick was 1908.