Today’s Tidbit... The Evolution of Yardage Markers and Field Numbers

Note: If you support Trump and his fascist ICE goons, you are not welcome here. Leave and do not return until you find your heart and brain. (I understand people come here for football content, not coverage of Trump’s immorality, but the times require us to be public about who we stand with and against.)

We have a host of rules and regulations today governing the markings that must or must not appear on football fields. Things were not always so. In the past, there was considerable experimentation with field markings, some of which made sense, and were adopted and incorporated into the code.

Football field markings initially included only the sidelines, goal lines, and midfield lines. The introduction of the system of downs led to yard lines every five yards between the goal lines, after which the field became a gridiron with 21 parallel, undifferentiated lines, plus two sidelines. There were no markings to distinguish one of the twenty-one lines from the other; it was difficult to know whether the ball was on the 20, 25, or 30-yard line. That could be problematic for players and fans, and worse for the officials, since marching off long penalties could be problematic. Back then, football had several 25-yard penalties, and did not cap half-the-distance penalties at 15 yards, meaning teams could be penalized up to 52 yards for one infraction.

Given the field’s limited information, early attempts to reduce confusion included special markings for the midfield stripe and the 25-yard lines. The midfield stripe divided the field in half and was the spot where kickoffs occurred, while the 25-yard line marked the spot for kickouts and following safeties.

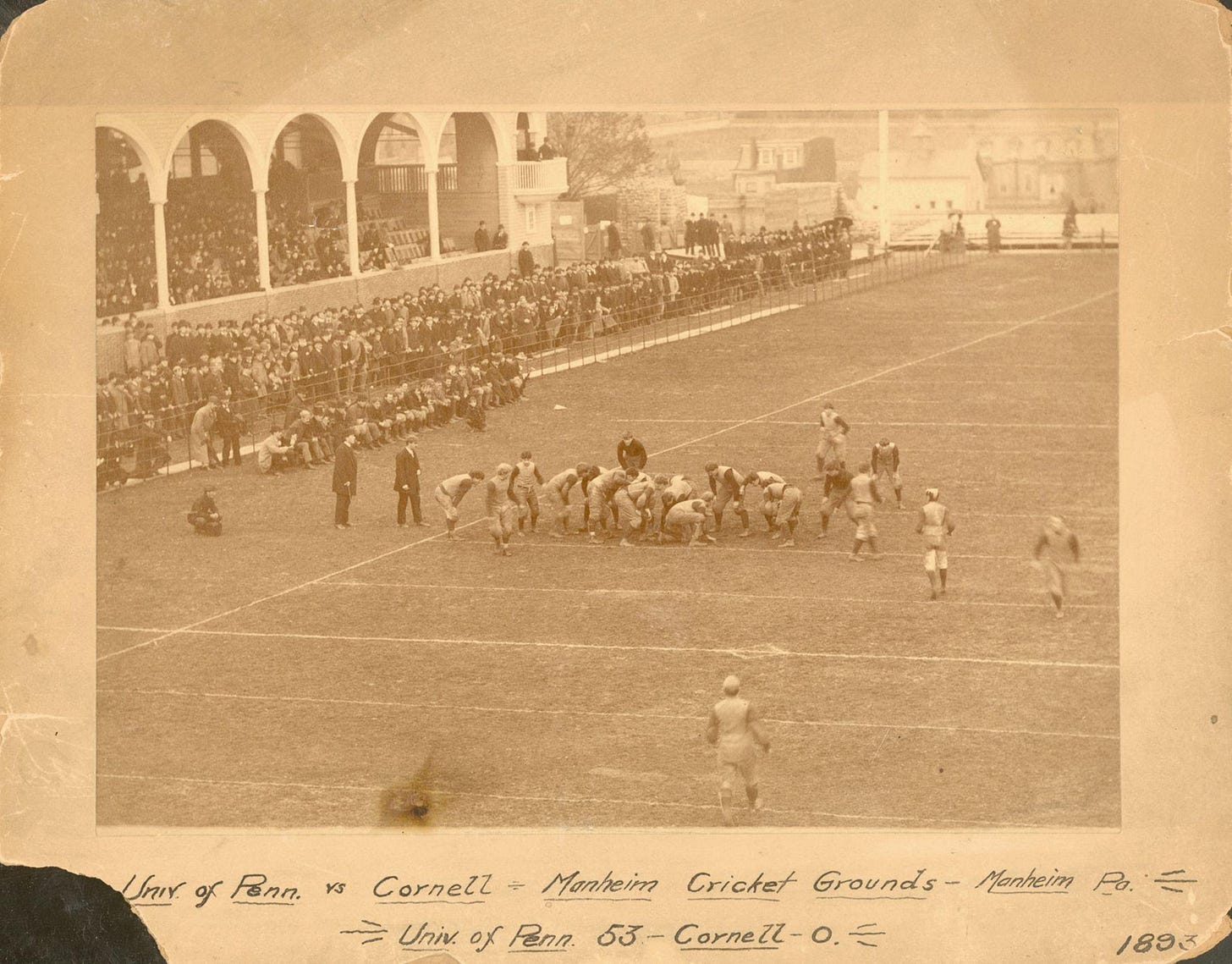

We can see early attempts to distinguish the yard lines in the image of the 1893 Penn-Cornell game at the Germantown Cricket Club. The players align for a scrimmage on the 36-yard line. We know it is the 36-yard line based on the diamond chalked on the 25-yard line immediately above the head of the safety at the bottom of the picture.

Presumably, similar diamonds appeared in the middle and on the other side of the field at the 55 and both 25-yard lines. In addition, the 25-yard line extends past the sideline, as do the 55-yard line and the other 25-yard line.

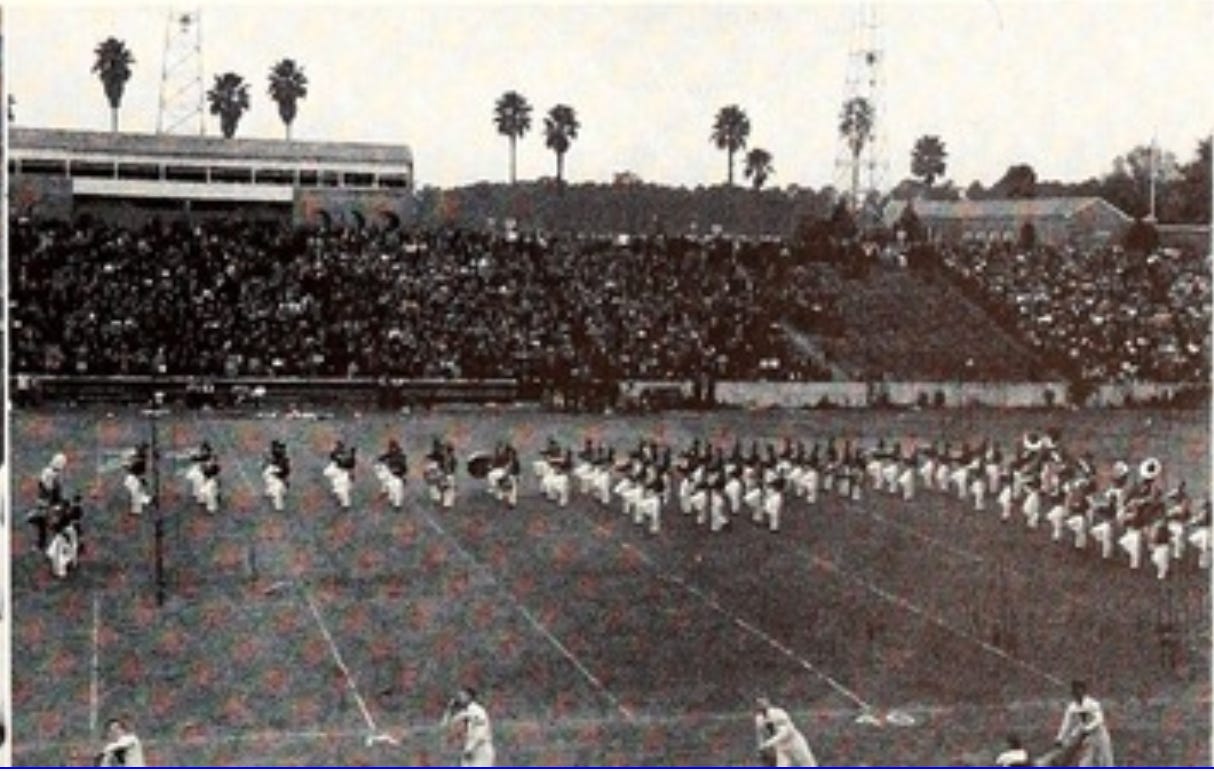

Within a few years, bigger stadiums hung signs every five or ten yards on the walls or fences surrounding the field.

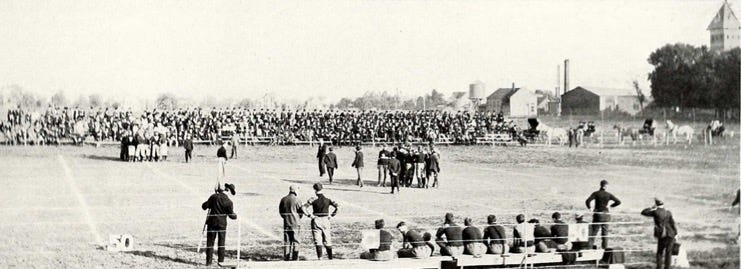

The yardage markers at Purdue’s Stuart Field in 1904 are interesting due to their designating the 55-yard line or center line with a “C.” (Images of midfield signage are hard to come by, a topic I’ll cover further in a few days.)

Yardage markers on fences and grandstands could be obscured by substitutes and people standing along the sidelines, so a host of other solutions emerged that placed signs closer to the sidelines.

[Moving the goal posts to the end line in 1927 led to all kinds of confusion about who was where on the field, so schools differentiated the goal lines in many ways. The article linked below addresses how they responded, including by decorating end zones and adding flags, now pylons, at the goal line.]

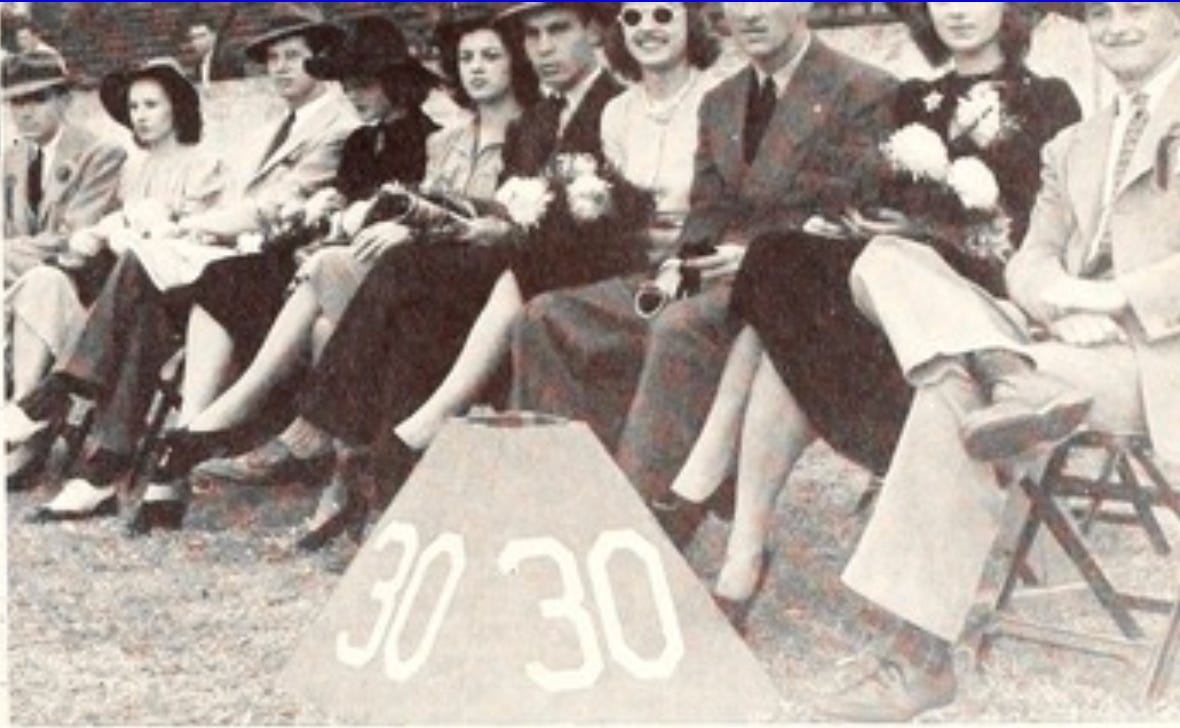

Placing yardage numbers on posts and metal stands resulted in injuries to players who hit those posts, leading to cardboard and rubber yardage markers by the 1930s. Some were A-frame or sandwich boards; the economy versions were old tires planted in the ground; and then there were my favorites, shaped like a trapezoidal prism.

Some stadiums painted a G or similar near the goal line in 1927 to distinguish the goal and end lines, followed soon thereafter by the arrival of field numbers. (Field numbers differ from yardage numbers by being chalked or painted directly on the field or just outside the sideline.)

Neither the NFL nor the NCAA required yardage or field numbers for many years. They also did not standardize their appearance or location, so there were many variations. Each location was free to include field numbers or not, and to paint them however they saw fit.

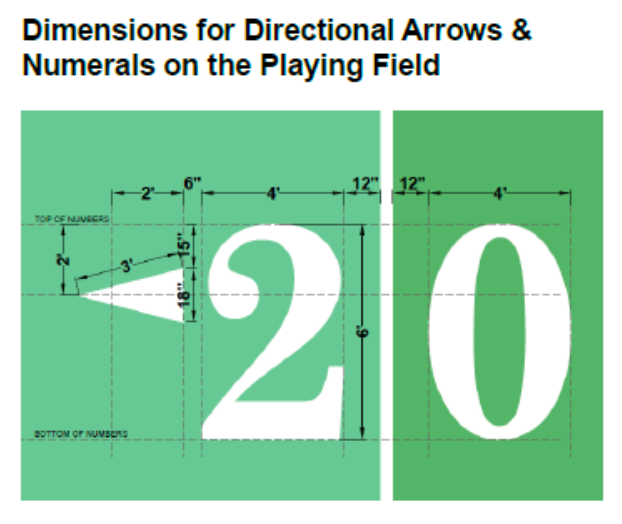

Television and the increased importance and sophistication of the passing game drove the desire for standardized field numbers. The field position was not always clear on television camera shots zoomed in from the press box, so adding field numbers helped solve that problem. In addition, quarterbacks and receivers used field numbers to define where to run routes and make cuts, which made varying field number styles problematic. The NFL standardized the location of its two-feet-tall field numbers in 1972, while also requiring the field to have outer Lockney Lines. The NFL required directional arrows next to the field numbers in 1978, also to help television viewers understand where the ball was on the field. The NCAA standardized the position and size of field numbers in 1982, though it has never required directional arrows.

Like all other field markings, the NFL and NCAA today have detailed standards for field numbers, though they require them only every 10 yards.

At the college level, some schools paint their field numbers every 5 yards, with LSU doing so since 1946.

The variations and additions to the field marking were chaotic at times, but some variations proved helpful and were adopted and standardized, improving the playing and viewing experience. So, while uniformity makes lots of sense, allowing for new ideas and experimentation with field markings is also a positive.

Regular readers support Football Archaeology. If you enjoy my work, get a paid subscription, buy me a coffee, or purchase a book.

Thank you for this, Tim. As a Canadian, I always looked forward to seeing a game from Edmonton since Commonwealth Stadium was a unique setting. Part of that across-the-airwaves ambience definitely was due to the natural grass field and its unique markings. They were gold, and I remember correctly, Edmonton painted the field numbers on the 5s (so 45, 35, 25...) and had '00' painted on the goal lines.

Right on, Tim.