What If We Dropkicked All Field Goals?

Note: If you support Trump and his fascist ICE goons, you are not welcome here. (I understand people come here for football content, not coverage of Trump’s immorality, but the times require us to be public about who we stand with and against.)

Imagine how different football would be today if we allowed only dropkicked field goals. The idea of banning placekicked field goals circulated after the 1897 season, a time when placekicked field goals were new and starting to affect big games.

We are all familiar with placekicked field goals. They occur today when the center snaps the ball to a holder, who sets it on the ground for the kicker. The process was only a year or two old in 1897, and most football folks had never seen one in person. They’d only read about them in the newspaper.

When football began in 1876, Rule 6 said:

A goal may be obtained by any kind of kick other than a punt.

The rules became more specific a few years later, detailing that goals could be scored by dropkick or placement kick. However, the norm was that field goal attempts were dropkicks, since they typically occurred from scrimmage, with the defense rushing the kicker as soon as the ball was snapped. From 1876 to the mid-1890s, placekicked field goal attempts were made only after a fair catch. The fair catch rule was obscure then and now, but it allowed teams making a fair catch to take a free kick, and since placekicks traveled farther than dropkicks, teams attempting a kick took the placement route.

They executed those placekicks just like they did free kicks on goals after touchdowns. The holder lay on his stomach or a side, arms extended along the ground, holding the ball just off the ground. The defense had to stand behind a restraining line and could rush the kicker only after the holder set the ball on the ground, so the holder placed the ball on the ground moments before the kicker booted it.

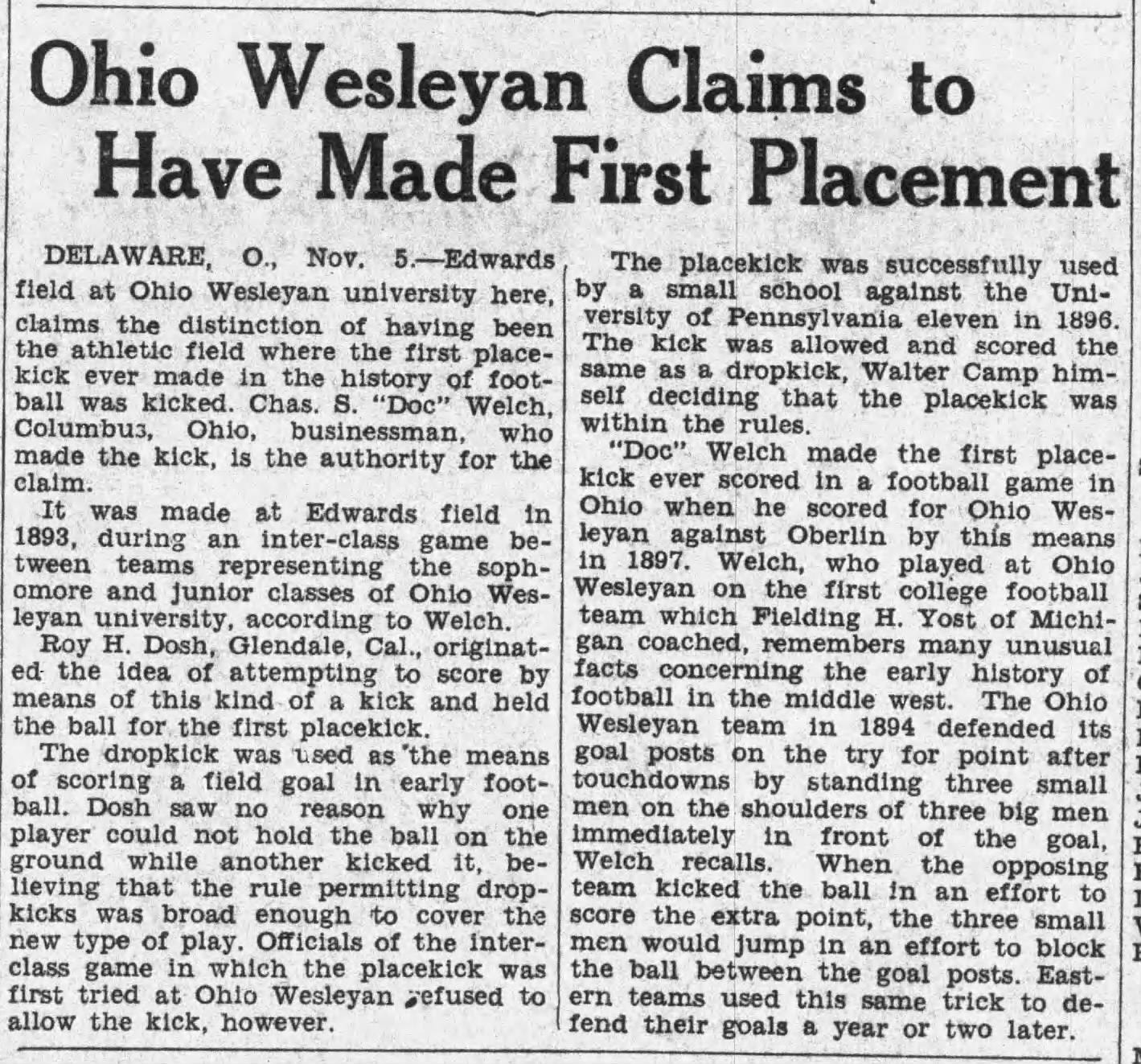

This general topic came up recently when I found a 1927 story about the origins of placement field goals. The story claimed that the first placement field goal occurred in 1893 during a Sophomore-Junior class game at Ohio Wesleyan. The article also noted that a small Ohio school executed a placement field goal against Penn in 1894 or 1895, and that the first placement kick in Ohio occurred in 1897 during Fielding Yost’s tenure as Ohio Wesleyan’s coach.

In looking into those claims, I found that not only did Penn not play a small college team from Ohio that year, but they did not face anyone from Ohio until they played OSU in 1933, so that part of the OWU story was in error. However, Oberlin attempted a placement field goal following a fair catch against Penn State in 1894, so that was likely the basis for that part of the story.

Free kicks following fair catches didn’t happen much then or now, so players, coaches, and the untrained officials of the time were often unaware that teams had the option, leading to in-game arguments later recounted in the newspaper. Additional searching found instances of placement field goals following fair catches in the 1880s, so Ohio Wesleyan’s claim of kicking the first placement field goal falls apart entirely. Despite OWU’s claims holding no water, investigating the claim revealed a controversy about whether placekicked field goals should be allowed at all.

Ohio Wesleyan’s claimed kick coincided with the actual first center-to-holder field goal attempt, invented by the Teter brothers of Ohio’s Otterbein College. The Teters had the holder catch the ball while squatting like a shortstop, while others had the holder use the one-knee approach we use today. After the Teters taught their new trick to players at Washington & Jefferson, W&J showed it to Princeton, who used it and got credit for what became known as the Princeton placekick. The Princeton place kick gained popularity in 1897, with its most advanced use coming at the University of Chicago. Chicago had a star fullback and kicker, Clarence Herschberger, who earned first-team Walter Camp All-American honors in 1898.

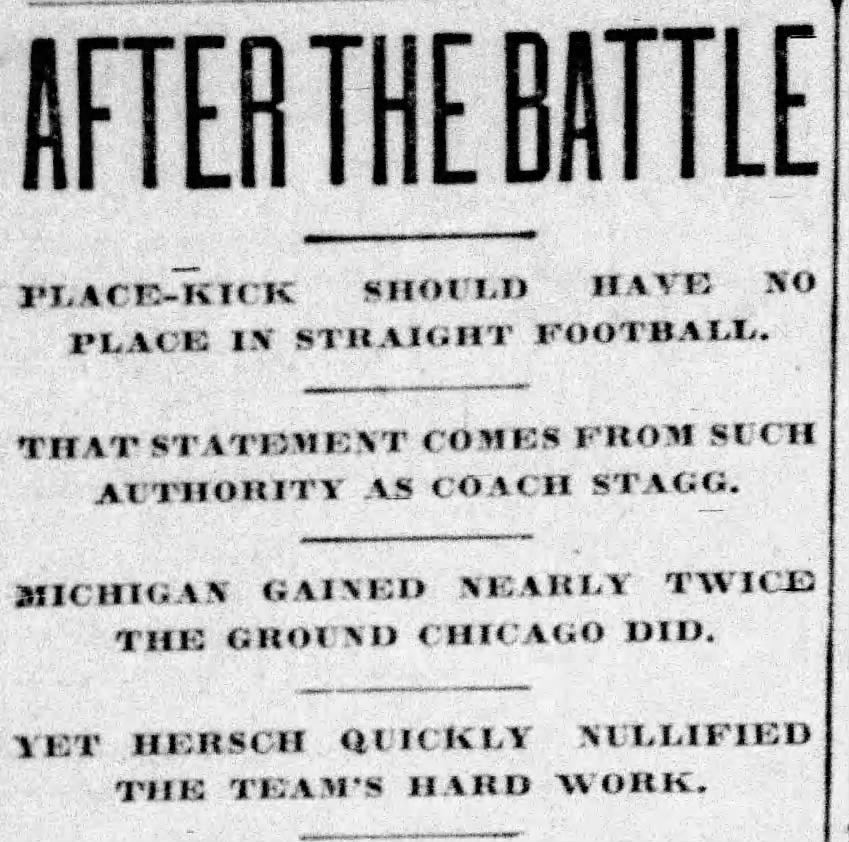

During the Maroons’ 1897 game against Michigan, played indoors in the Chicago Coliseum, Herschberger outscored Michigan by making three placement field goals -each worth 5 points- as Chicago won 21-12. The ease with which Chicago kicked field goals raised concerns that teams might begin choosing to kick field goals rather than work for touchdowns. Since that line of thinking ran counter to the growing sentiment favoring touchdowns scored through team play rather than kicks by a single player.

While placekicked field goals were legal in 1897, some argued that they were a flaw in the rules and should be banned. Ironically, Herschberger’s coach, Amos Alonzo Stagg, was among the first voices calling for the ban on placekicked field goals.

Eddie Cochems, Wisconsin’s captain and later the Father of the Forward Pass, was another voice that supported the elimination of the placement field goal.

Rather than eliminate placement field goals, the rulemakers of 1898 changed the scoring system so that touchdowns and field goals were both worth five points, rather than touchdowns being worth only four. The rule change made touchdowns worth the same points as field goals and gave teams the chance to earn another point via the goal after touchdown.

So, the 1898 rulemakers opted to keep the placement kick for field goals, and the challenge against placement kicks seldom resurfaced. Still, it’s fun to speculate how the game might be different now if the ban had occurred. Here are a few questions to consider:

If all field goals had to occur by dropkick, would the ball have been reshaped in 1929 and 1934, making it easier to throw and harder to dropkick?

Would football have kept the goal posts on the goal line rather than moving them to the end line in 1927?

Would specialist dropkickers have developed in the same way as specialist placekickers?

How would offensive strategy change in a world where teams had to penetrate further into their opponents’ territory to attempt a field goal?

How else might the game have changed if we had banned placekicked field goals?

Regular readers support Football Archaeology. If you enjoy my work, get a paid subscription, buy me a coffee, or purchase a book.

One of the things I've always noticed in the Marx Brothers movie "Horsefeathers" is that the holder is lying on his stomach during placekicks. For me that was more bizarre than any of the actual Marx Brothers antics.