Rerun: When The Olympics Included Gridiron Football

Originally published in June 2021, this story applies to those who love the Olympics and gridiron football. It is republished today for the opening of the 2024 Paris Olympics.

The Tokyo Summer Olympics are upon us, and gridiron football will again be absent, but our dear game was part of the 1904 St. Louis and 1932 Los Angeles games. Sort of.

We all know the modern Olympics began in Athens in 1896, followed by the Paris Games of 1900, which included events familiar and strange. The International Olympic Committee awarded Chicago the 1904 games, putting the City of Wind in competition with the St. Louis World's Fair that drew nearly twenty million visitors that summer. In due time, A. G. Spalding, who helped win the games for Chicago and his sporting goods firm, saw the wisdom of fielding the games where more attendees might see the events and Spalding equipment, so St. Louis it was.

The St. Louis World's Fair came during the 101st anniversary of the Louisiana Purchase, an area populated at the time of sale almost exclusively by Native Americans. The Fair's leadership included a Director of Physical Culture, who scheduled a range of athletic events during the Fair's seven-month run. Sporting events included high school track & field, college football and baseball, professional cycling, and many others. The open competitions comprising the core Olympic games occurred over five days in late August and early September. Most participants competed for club teams since national teams did not yet exist.

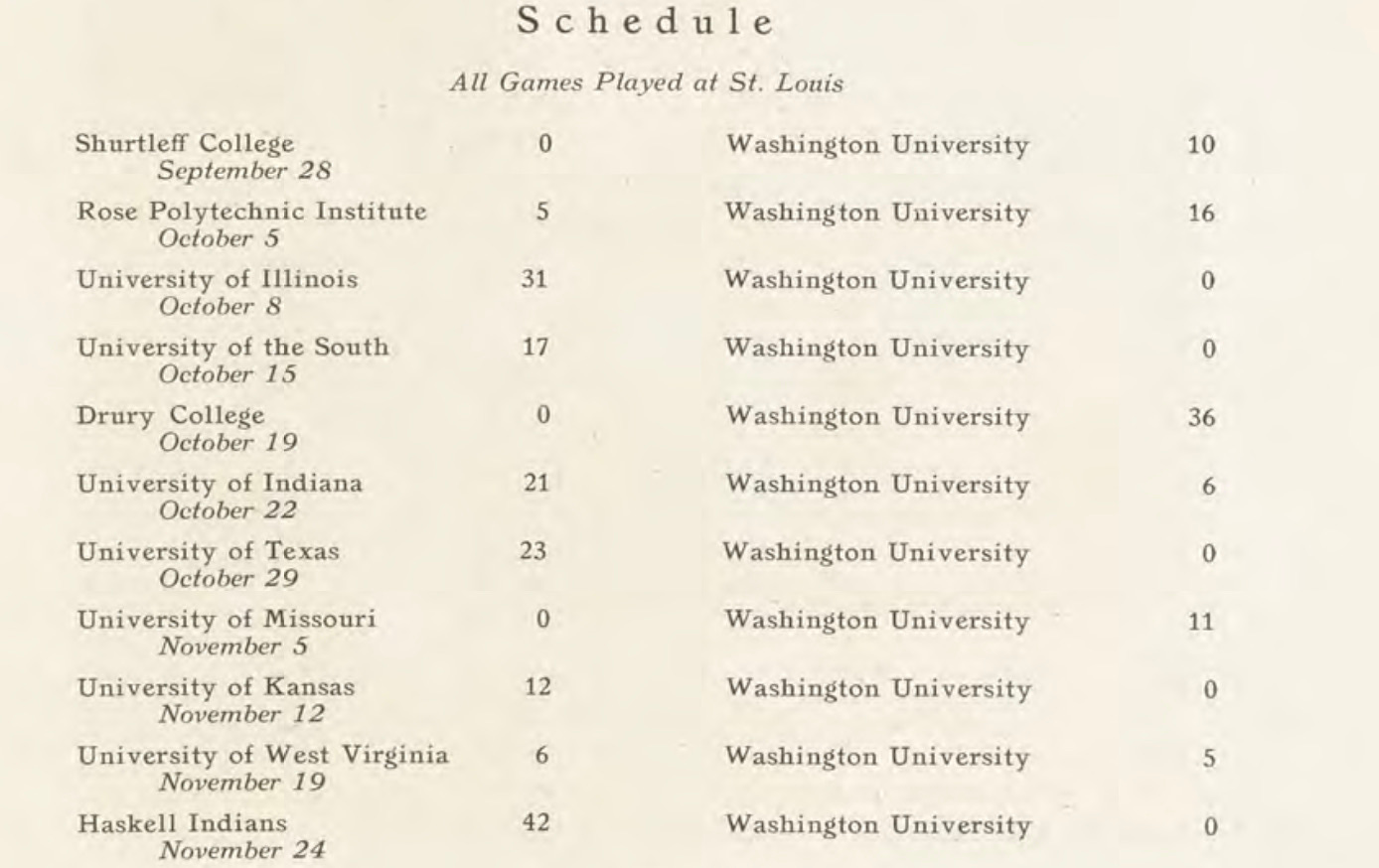

Determining which competitions were Olympic and which were part of the Fair was unclear at the time. Period sources such as Spalding's Official Athletic Almanac for 1905 covered the previous year's events and considered many more events part of the Olympic festivities than the International Olympic Committee recognizes today. The Almanac considered college football an Olympic event, but it was a tough argument to make even then, given what transpired at those games.

The AAU and college football steering committees that helped coordinate football at the games included luminaries such as Casper Whitney (he originated All-America teams in 1889), Walter Camp, Paul Dashiell, and Amos Alonzo Stagg. The initial thinking called for a tournament or intersectional football games, but none of the nationally prominent teams wanted to participate in a football tournament that overlapped their regular season. There was no money in it. After dropping that idea, the two most prominent local teams -Washington University and St. Louis University- became part of the show. Sort of.

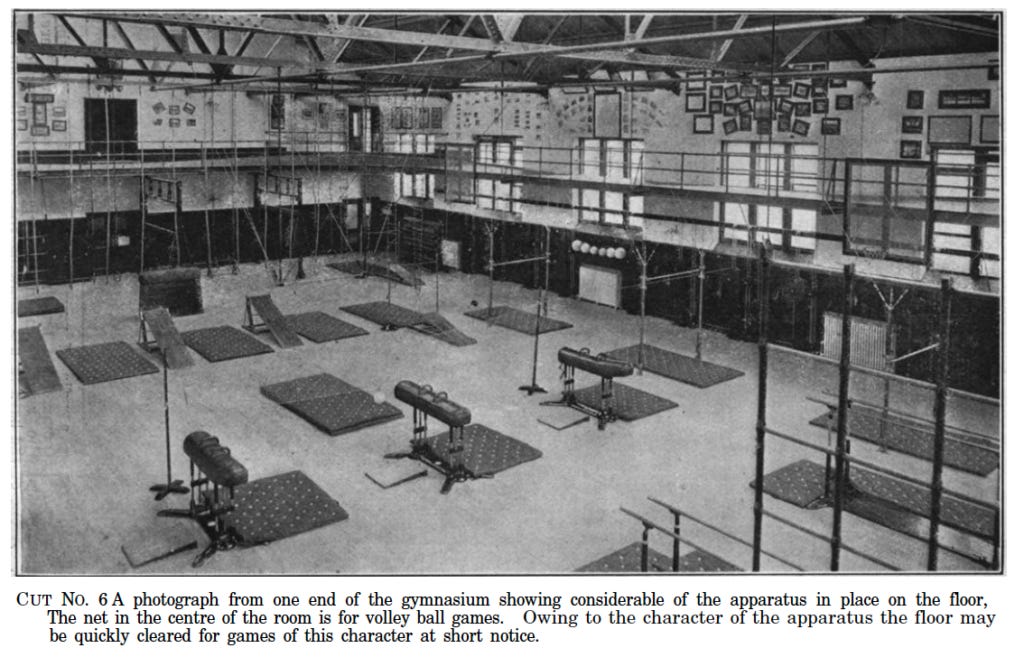

Most of the World's Fair occurred in extravagant but temporary buildings in what became St. Louis' Forest Park. In contrast, several permanent structures, including the sports stadium, were built across the street, forming the core of WashU's Hilltop Campus. Playing an eleven-game schedule in the stadium that remains their home field, WashU attracted a solid set of opponents since those teams could spend a few days at the Fair and play a game in a big city.

Another contest sometimes considered part of the Games was a battle between Carlisle and Haskell, the best Indian School football teams of the day. The schools were rivals since students often transferred from one to another (Jim Thorpe being one) for educational reasons and to take advantage of the already loose eligibility rules. Scheduled for the Saturday after Thanksgiving, it was Roosevelt Day at the Fair, and President Teddy promised to attend.

Unfortunately, Roosevelt never appeared at the game, as Carlisle rolled to a 38-4 win.

Remember St. Louis U? They went 11-0 that year, outscoring opponents 344 to 0, but faced inferior competition. Only their 5-0 win over Kentucky University, now Transylvania College, and the 17-0 win over Missouri came against somewhat competitive programs. However, since SLU was the only school to agree to the Olympic committee's financial requirements, SLU was named the Olympic football champions by default despite not playing a game at the Olympic stadium. The IOC does not recognize their championship today, and neither should anyone else.

Beyond the football games already discussed, two individuals competed in the 1904 Olympics with football connections worthy of mention. George Varnell, profiled in this post, placed fourth of four in two hurdle events. He played for UChicago in 1904 and Transylvania in 1905 and later became a leading sports editor in the Northwest and football official, handling six Rose Bowls. The other notable "Olympian" participated in Anthropology Days, a two-day experimental event in which tribesmen and assorted others from the World's Fair cultural exhibits competed in track and field and similar events as an ethnological test. Lone Star Dietz won the shot put and placed in the 400-meter run and baseball throw. Dietz played and assisted at Carlisle under Pop Warner a few years later. He then coached Washington State to the 1916 Rose Bowl and the Mare Island Marines to the 1919 Rose Bowl before heading other college and pro teams during a 35-year coaching journey.

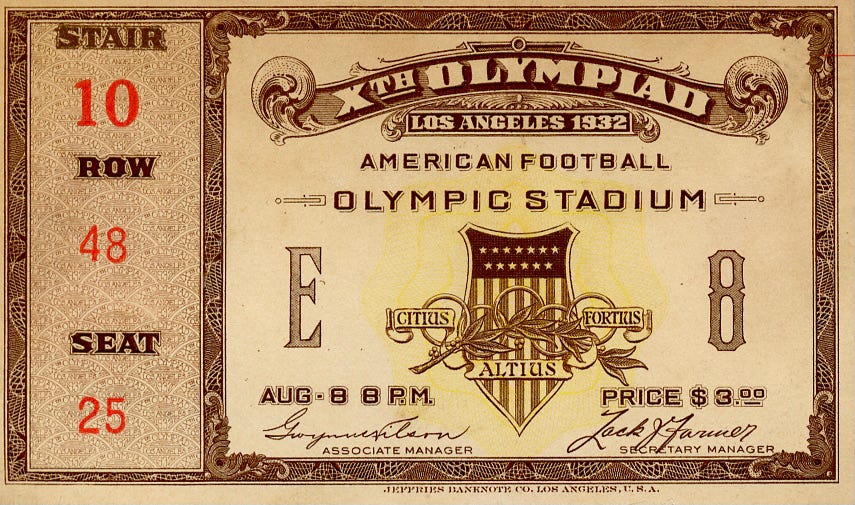

The inclusion of football in the 1932 Olympics was more straightforward. By then, the Olympics had developed a standard set of events, but host countries could include two demonstration sports of their choice. Los Angeles chose football and lacrosse. Recognizing the colleges would not allow their football teams to play for free while preparing for their money-making college seasons, the Los Angeles Committee took a different approach. Announced a year before the game, they planned a game between Eastern and Western All-Star teams. The Eastern squad included 1932 graduates of Harvard, Yale, and Princeton, while the Western players were similar grads of Stanford, Cal, and USC. Former Yale coach Tad Jones led the Easterners while his older brother, USC coach Howard Jones, helmed the Westerners.

By 1932, there was some intersectional play during the regular season among the colleges, and the only consistent postseason games were the Rose Bowl, played eighteen times, and the seven-year-old East-West Shrine Game. With so few opportunities to compare the merits of teams from different parts of the country, a game of Eastern and Western All-Stars at the Olympics captured the football world's imagination, mainly because none of the participating teams had ever played one from the other region. (The 1949 Harvard-Stanford game remains the only exception.)

Each coach had solid assistants from their sibling schools -Pop Warner assisted the West—and both respected the prohibition against scouting one another during their three weeks of practice. The mix of coaching philosophies on each staff and the lack of scouting meant the East and West prepared without knowing what the other might do.

Played at night so competitors from other countries could see American football, it was the first contest under the 1932 rule that stopped play when a runner went to the ground. (Until then, the ball carrier could get up or crawl forward if not held on the ground by an opponent.) Despite the new rule causing some confusion among players and fans, the 70,000 attendees at the Coliseum (aka Olympic Stadium) saw a well-played game with limited scoring. The West moved the ball inside the red zone three times in the first half, but the East held each time. The first score came in the fourth quarter when the East's missed field goal attempt bounced off a West player or two before Yale's Burton Strange fell on it in the end zone for the score. The East missed the PAT before the West drove the field's length with USC's All-America quarterback, Gus Shaver, scoring on fourth and goal from inside the one. The made PAT gave the Left Coasters a 7-6 victory.

While the Americans in the crowd enjoyed the game, observers in the foreign press considered it brutal and complex, with too many stoppages of play and substitutions. That view has not changed in the ensuing ninety-eight years. Besides Canada, no other country has adopted gridiron football beyond small slices of interest in some countries. Folks elsewhere live for different sports, mostly the other game they call football, so we will likely wait some time before the tackle version of gridiron football comes to an Olympics near you.

Click here for options on how to support this site beyond a free subscription.