When Tipped Passes Were Live Balls

A Tidbit from a few days ago covered the long period during which fumbles, blocked kicks, and other balls remained live after going out of bounds. Today's Tidbit covers the four years when incomplete passes that touched a player while in the air were similarly ruled to be live balls, resulting in similar crazy scrambles for the ball.

Football was in crisis following the 1905 season, and they made numerous rule changes to open the game and make it safer. The rule makers had a lot to deal with and only so much time to agree on the new rules, so the early forward-passing rules did not get the attention they deserved. In addition, the rule makers struggled to envision which rules were required since they could not foresee what the game would look like after legalizing the forward pass. The result was a limited set of rules governing the forward pass.

Here are shorthand versions of the passing rules for 1906:

The offense can throw one forward pass per play, and only players behind the line of scrimmage at the snap can throw a forward pass.

Incomplete passes and passes thrown by linemen result in turnovers (spotted at the location of the pass).

Passes touched by ineligible receivers are turnovers (spot foul).

Passes thrown from a spot within five yards left or right of the center are turnovers (spot foul).

Forward passes thrown by the defense are illegal (spot foul).

Passes crossing the goal line without touching a player on either side, whether on the fly or bounding, are illegal and result in a touchback.

That was the entirety of the rules covering the passing game. Missing from the rules was any discussion of pass interference. Pass interference arrived in 1908, but not in the form you might think.

The forward pass saw limited use in 1906 as most teams struggled to conceive of play designs, pass-blocking techniques, routes, and throwing and catching techniques. Losing possession of the ball on incompletions reduced teams' willingness to toss the pea, especially when on their side of the 55-yard line.

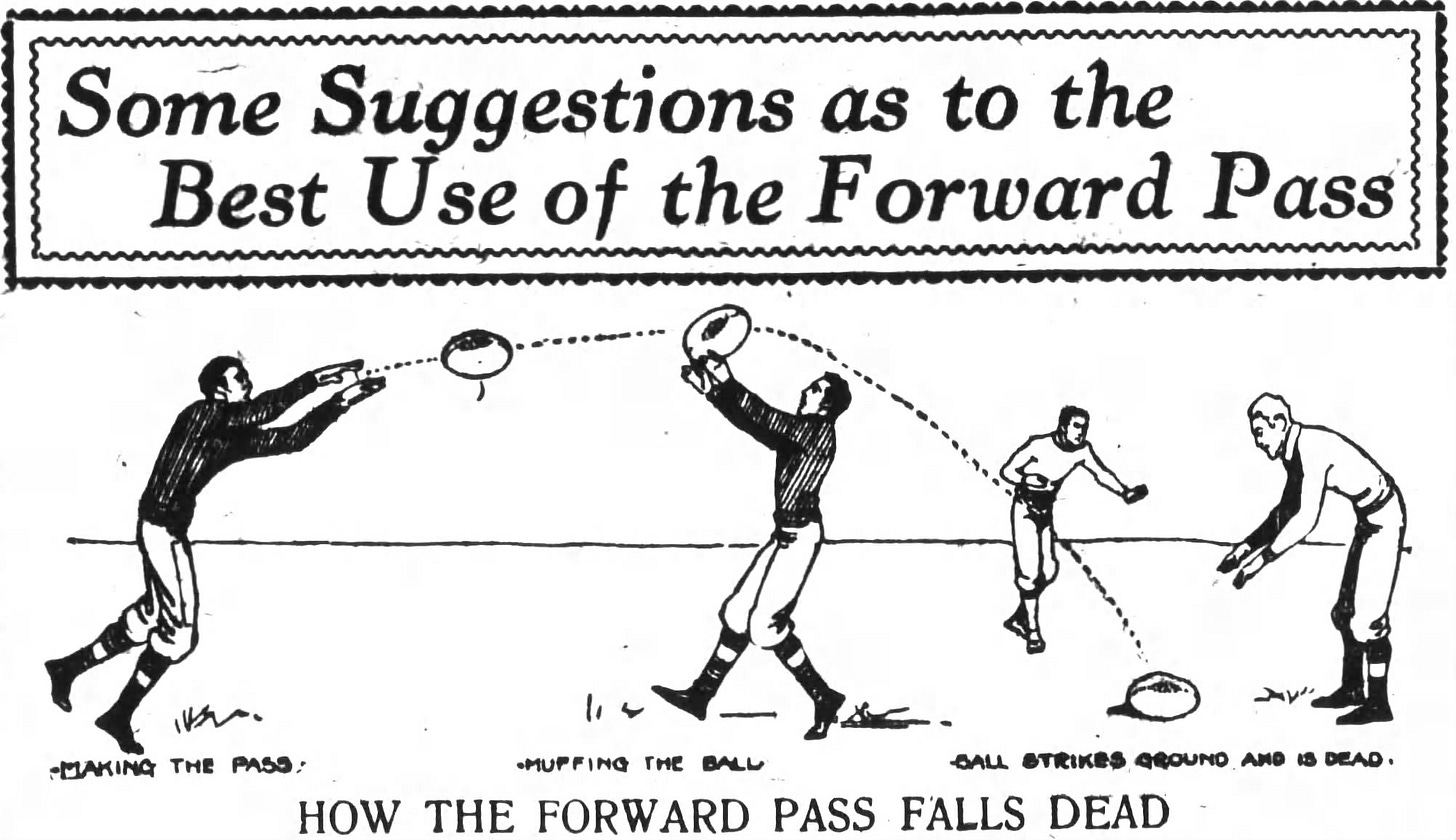

Despite some teams having success throwing the ball in 1906, most used it only as a desperation play, so the 1907 rules reduced the penalty for an incomplete pass from a turnover to a 15-yard penalty and the loss of the down. Another 1907 change modified the definition of an incompletion. An incompletion, or an "uncompleted pass" as they called it in the rule book, was a legal forward pass that hit the ground in the field of play without first touching a player.

However, a rugby-influenced 1907 rule change was Rule XIX, Section 5 (c), which made the ball live if a player on either side touched it before hitting the ground. After hitting the ground, players from either side try to gain possession of the loose ball.

The rule meant that dropped passes, balls going off receivers’ fingertips, balls tipped or batted by a defender, or balls striking an offensive or defensive player in the back of the head all became fumbles recoverable by anyone, and these tipped passes led to mad scrambles for the ball.

Many coaches argued for removing the forward pass, while others wanted it retained. The opponents of the pass viewed the scrambles for the ball as problematic, but coaches like Carlisle's Pop Warner countered:

"Take it [the forward pass] away and the game will revert to the old line-plunging game, which no one wants to see reinstated. It is true it causes much scramble for the ball, but this is true of the onside kick [from scrimmage], and these two plays are the only ones which cause the defense to scatter."

'Forward Pass Too Lucky, Say Experts,' Los Angeles Times, December 29, 1907.

Some early pass plays resembled rugby lineouts in that the offensive linemen, who could legally go downfield on passes, would encircle and lift a teammate into the air as the ball was thrown to him. Since rules about pass interference did not yet exist, defenders rushed into the groups, potentially causing the ball to hit several players before hitting the ground. To limit the "lineouts" and scrambles, a 1908 rule made it so only the first offensive player to touch the ball on a play could catch it or recover the "fumble" unless a defensive player also touched it. (This was the rationale for the longstanding rule keeping offensive players from touching a pass after a teammate did so.)

An example scramble in which the intended receiver recovered a dropped ball came when Carlisle visited Penn in 1909, a game made famous due to Carlisle's Wauseka striking the umpire, Big Bill Edwards, and being ejected from the game. His coach, Pop Warner, protested the call and was also sent to the locker room. Later in the game, Penn tried a forward pass that touched a Quaker player in flight, who then recovered the dropped ball:

"The going was rather slow, so Miller tried a forward pass. Braddock touched the ball, but could not hold it. That made a scramble for possession of the pigskin. Braddock finally got it on the 5-yard line, from where Heilman took it over in one plunge. Miller punted out to Marks and Braddock kicked the goal."

'Wauseka and Fretz and Coach Warner Ruled Off The Field -- Umpire Is Attacked,' Philadelphia Inquirer, October 31, 1909.

Despite attempts to limit the scramble following "fumbled" passes, they remained dangerous, so the rule makers of 1911 eliminated the scrambles by treating tipped passes hitting the ground as ordinary incomplete passes.

The days of fumbled pass scramble were over, but it took longer before the forward pass took off. The game continued changing, eventually reducing and eliminating penalties for incompletions, though they survived in some form into the 1930s. Over time, changes in play designs, pass-blocking rules, defensive restrictions, and other changes made the forward pass an integral, if not the leading, element of the game. Still, it took some crazy experimenting and trial-and-error for the game to evolve as it has.

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to buy one of my books or otherwise support the site.

Great developmental information about evolution of the forward pass. You really had to write this one clearly and carefully to properly communicate several of these finer points, too. Well done, Tim!