Factoid Feast XVII

As discussed in Factoid Feasts I, II, III, IV, V, VI, VII, VIII, IX, X, XI, XII, XIII, XIV, XV, and XVI, my searches through football history sometimes lead to topics too important to ignore but too minor to Tidbit. Such nuggets are factoids, three of which are shared today.

The latest version of Factoid Feast celebrates the dishonest and honest behavior of coaches.

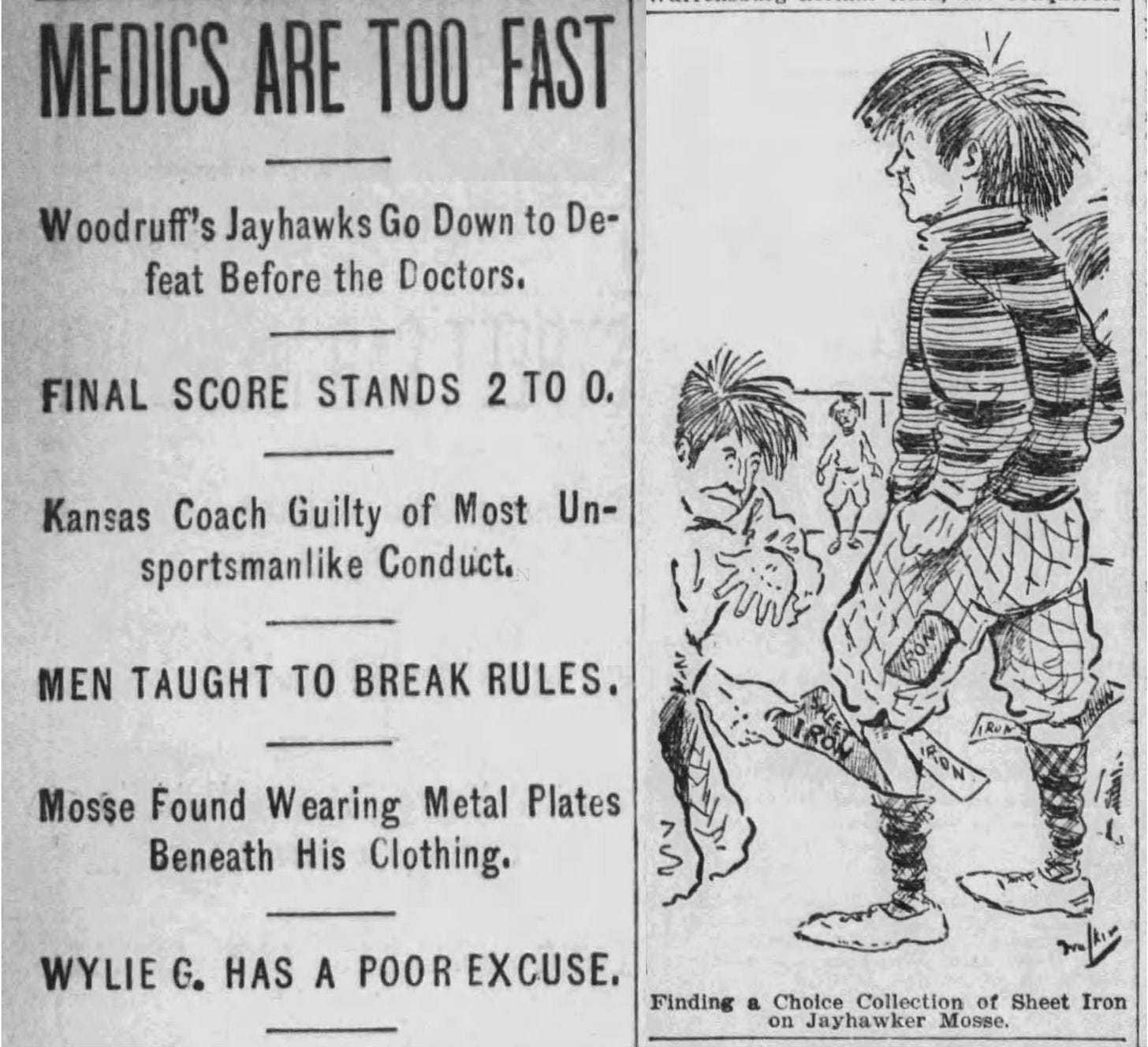

A Will and Shins of Iron

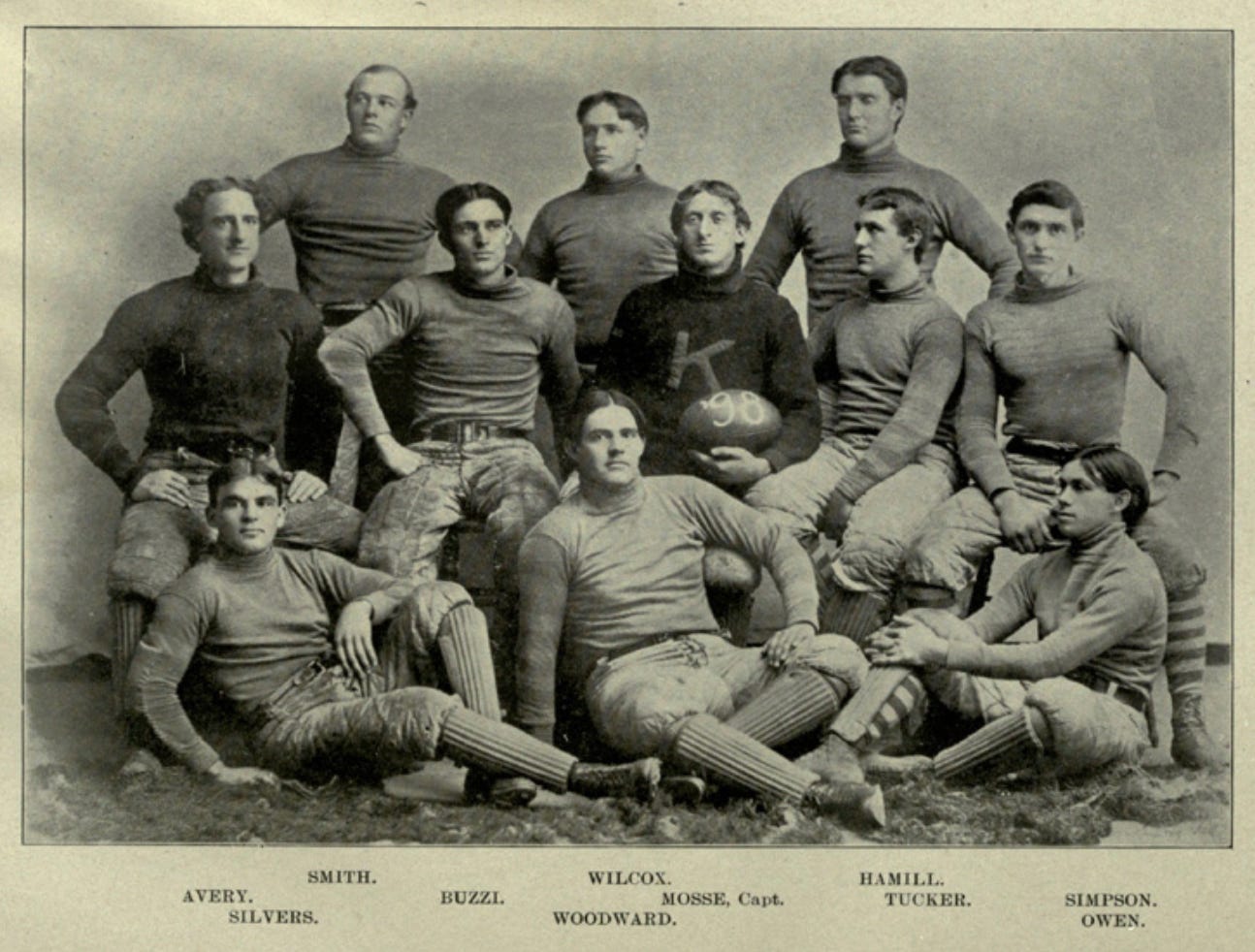

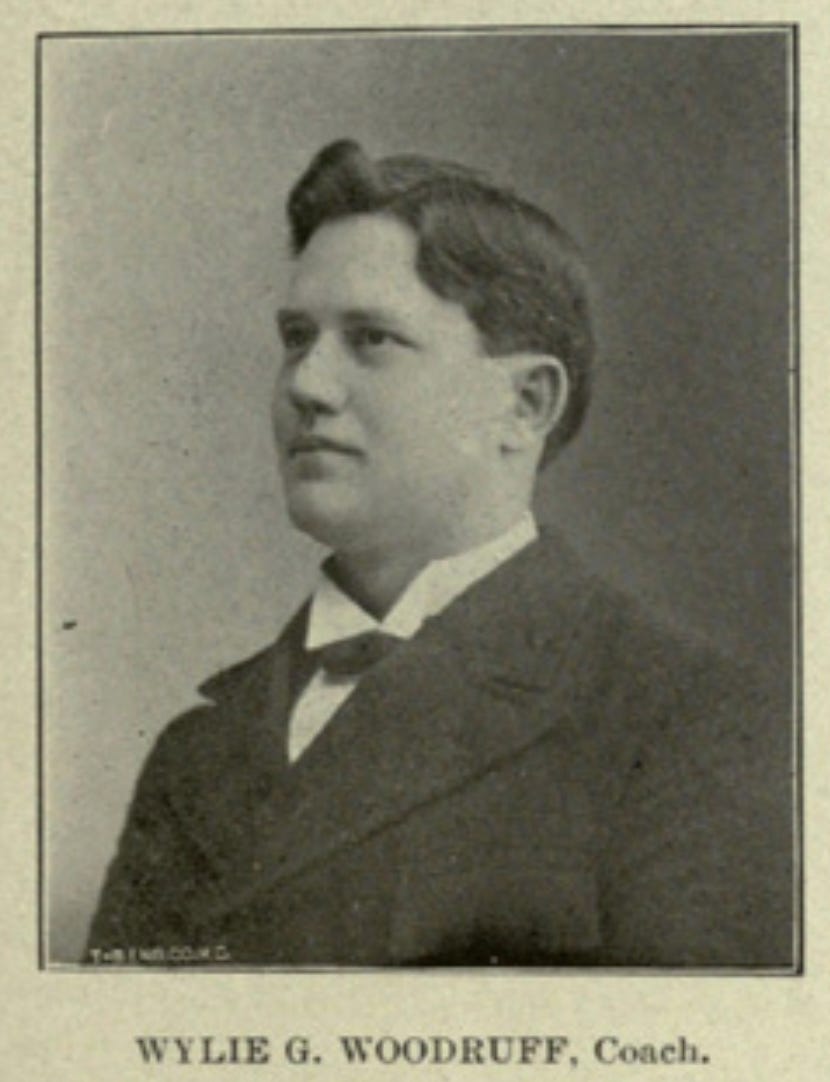

Wylie G. Woodruff played football for Penn from 1893 to 1896 while earning a medical degree. Upon graduating, he took a commission in the Army Medical Corps, receiving an assignment at Fort Riley, Kansas. However, Woodruff earned a leave of absence to coach the Kansas football team in 1897.

During a game played against the Kansas City Medics, which represented the state’s medical school, Coach Woodruff got himself in trouble. The Medics received advance warning that a Kansas guard named Arthur Mosse wore iron pads during games. When a Medics player who opposed Mosse became injured, they complained to the referee, who ordered Mosse to the sidelines to remove the offending gear.

As fans of both sides watched, Mosse cut galvanized iron sheets from his shin guards and thigh pads, equipment that clearly violated the rules against gear composed of unyielding materials. Challenged by fans and reporters, Woodruff acknowledged that he had approved the devices and claimed that iron pads were commonly worn in the East, although there is little evidence to support his claim. Mosse returned to the game, having ironed out the situation, and Kansas lost 2-0 to the Medics.

The team voted Mosse as their captain for the 1898 season, Woodruff’s last on the sidelines, as he focused on his private practice, which was disrupted due to accusations that he was having an affair with a married patient. His subsequent divorce, relocation, and marriage to his former patient suggest it was more than an accusation.

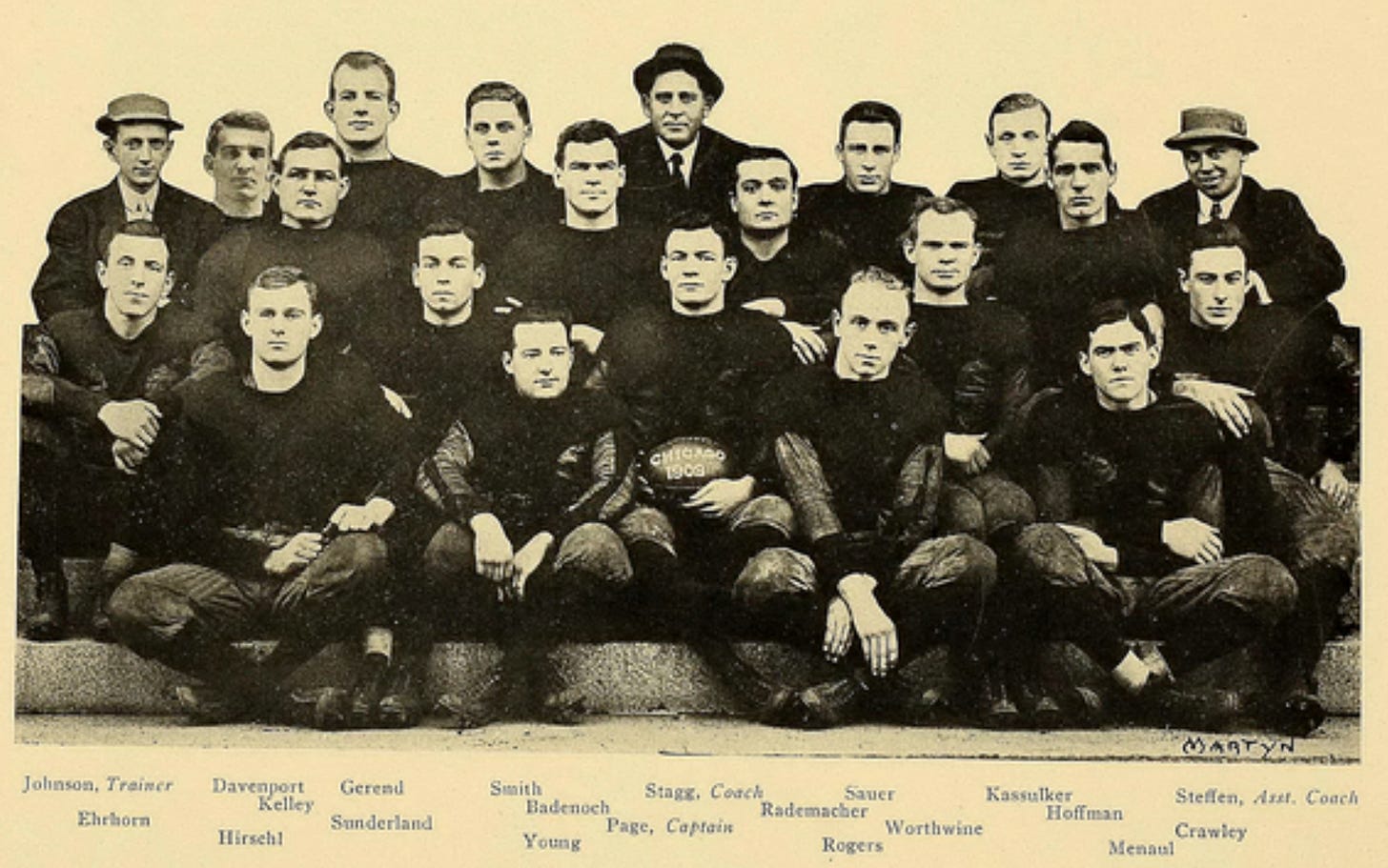

Stagg Overrules the Referee

Amos Alonzo Stagg had excellent teams in the first decade of the 1900s. He was in his 18th season coaching the Monsters of the Midway when his 3-1 Maroons hosted Northwestern in 1909. Midway through the first half, down by a touchdown or two, Northwestern punted from close to its goal line. The ball sailed downfield where Pat Page, Chicago’s quarterback, caught it.

Page immediately return kicked the ball, meaning he punted it back toward Northwestern’s goal, where it appeared to hit a Northwestern player. Chicago tackle Arthur Hoffman picked up the “loose” ball and ran it in for the score.

Northwestern’s fans were displeased with the result of the play and with Stagg, who ran onto the field to confer with the ref. As it turned out, Stagg argued with the referee that the ball had not touched the Northwestern player. Rather than a Chicago score, Stagg said the ball should be Northwestern’s at the spot where Chicago’s Hoffman picked up the ball.

Stagg won the argument, the referee gave Northwestern the ball, and Chicago went on to a 34-0 victory in a game won honestly.

He Nailed It

Jock Sutherland was Pitt’s coach in 1928 when he wrote a story that may have been autobiographical. The story went that Coach A, presumably Sutherland, was to face Coach B, who was known to violate football’s rule against coaching from the sideline.

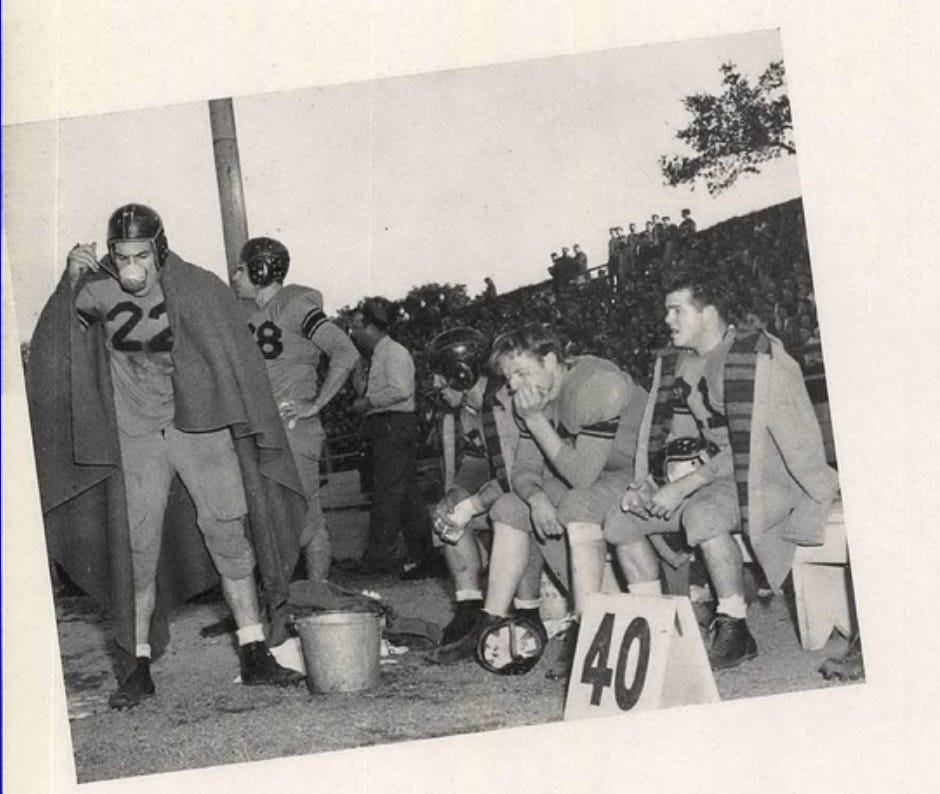

At the time, coaches were not allowed to communicate with players during games, and all coaches and substitutes were required to remain seated on the bench throughout the game. In addition, a common practice at the time was to have a water bucket and scoop along the sideline for players to refresh themselves during timeouts.

One of Coach B’s tactics was to place his team’s bench close to the sideline, allowing him to whisper instructions to his team during water breaks. To prevent that from happening, when Coach B’s team played on Coach A’s field, Coach A had the stadium crew securely nail the visiting team’s bench in place, far from the sideline.

As the teams took the field to start the game, Coach B tried lifting the bench to drag it toward the sideline but found it immovable. Coach B and his assistants tugged mightily at the bench before giving up. Coach A watched their antics from the opposite sideline, knowing that Coach B would have to watch the game from a proper distance behind the sideline.

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to donate a couple of bucks, buy one of my books, or otherwise support the site.

Here’s my lineup of books:

Love what Stage represented and how he handled himself in the realm of football. Truly one of the greats.