The 1904 Little Big Game: We Shall Not See Its Like Again

As Walter Camp and his buddies at Yale prepared for their 1876 game with Harvard, they had limited knowledge of rugby besides the information gleaned from the rule book. Only one Yale team member had ever seen a regulation rugby match, though several played in the 1875 Harvard-Yale match that used compromise or concessionary rules combining rugby, soccer, and local folk rules.

Their situation was typical of the time. Early players learned rugby by reading the rule book and interpreting it as best they could. The early rules were neither detailed nor clear, and since few had playing experience, the rules were often misunderstood. In time, the rules became increasingly detailed to address the situations they had not anticipated and to close loopholes some used to violate the law's spirit when the letter went missing.

The rules have since become more detailed and clear -at least to rules junkies- but it took time for rules omissions to get filled in. One example was covered previously in The 125-Year-Old Safety Penalty, and another, which came during the 1904 Little Big Game, is covered in this story. The Little Big Game was the annual contest between Cal and Stanford's freshmen teams. While we might scoff at freshmen games today -they now exist primarily at the DIII level- fans once followed freshmen games as signs of things to come, much like we treat recruiting rankings today. They received press coverage; a few, like the Little Big Game, were big events.

The 1904 game and story hinge on several rules that are no longer part of American football -the onside punt and the return kick. (Both remain in Canadian football.) Before 1906, the onside punt, aka the quarterback kick, allowed members of the kicking team positioned behind the punter, and therefore "onside," to run downfield and recover the punted ball, much like recovering an onside kickoff today. (From 1906 to 1922, everyone on the punting team could recover the ball regardless of their location relative to the punter.)

Besides the onside punt, there was the return kick, which the NCAA did not eliminate until 1967. Through the 1966 season, players fielding a kick or punt, intercepting a pass, or recovering a fumble could immediately punt the ball back to the other team. It seems like a crazy tactic today, but it made sense for teams with strong defenses in the field position-oriented games of the past.

So, here's what happened in the Little Big Game. California was leading 5-0 after scoring a touchdown and failing on the extra-point try. With the ball on their own 20-yard line, the Bears punted to Stanford. At the time, fullbacks handled the punting for most teams -so much so that the rule book had a "roughing the fullback" penalty, not roughing the punter.

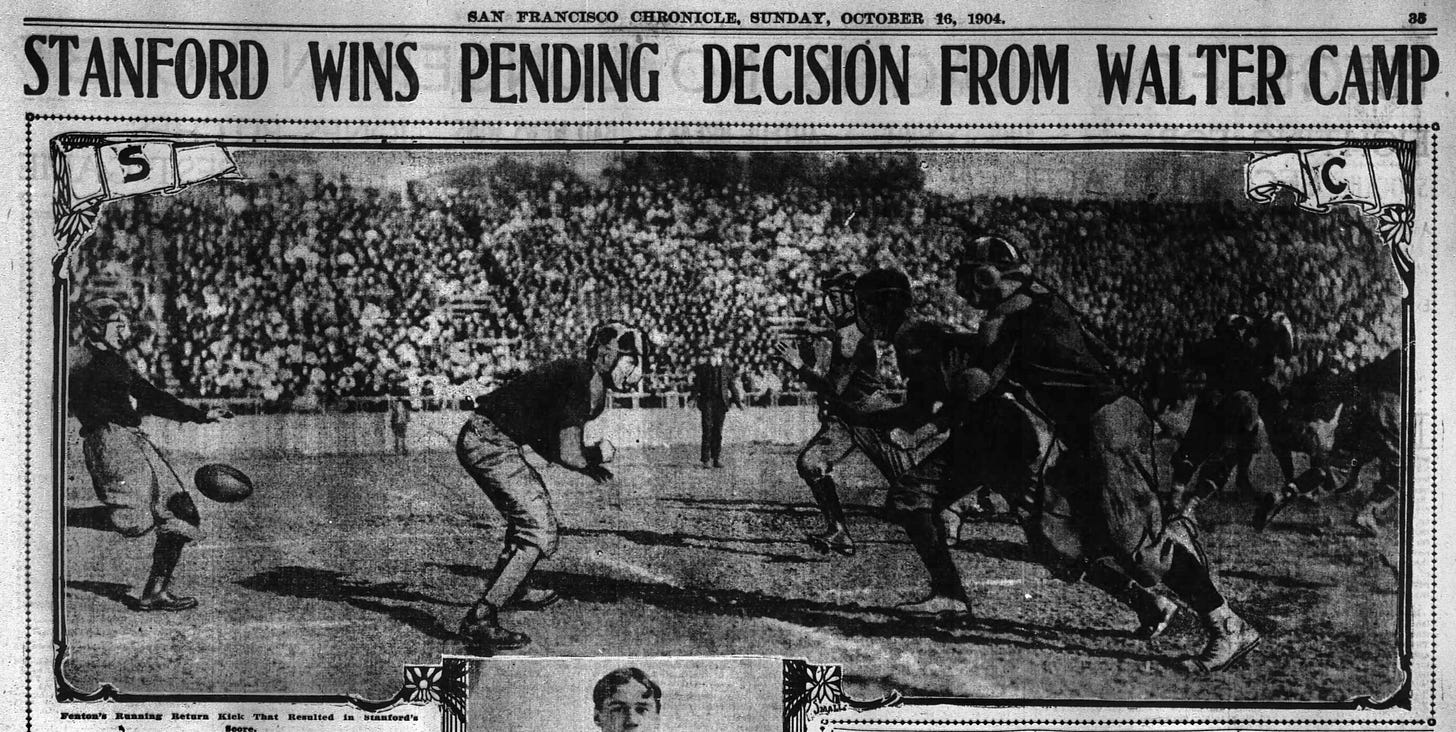

Stanford's quarterback, A. L. Fenton, was in the deep safety position. He fielded Cal's thirty-five-yard punt at midfield, immediately return kicked it back to Cal, and raced toward the goal line to cover the punt.

Fenton's boot sailed forty yards in the air, landed on the 15-yard line, and rolled toward the goal line. Thinking the ball would continue over the goal line for a touchback, Cal's players let it roll. Meanwhile, Fenton's teammates did not touch the ball due to a third rule. Since Fenton had been back deep to field the punt, his teammates were closer to Cal's goal line than Fenton as he return kicked the ball, making them "offside" and unable to touch the ball inside Cal’s 10-yard line without causing a touchback.

As the ball slowly rolled inside the 1-yard line, Fenton came flying in from his safety position and landed on the ball for the recovery, setting off a controversy.

As described in the roughing the fullback article linked above, the rules of the time did not allow punters to recover the ball during a play in which his team started from scrimmage. However, the rules did not prohibit him from recovering the ball on a return kick. The rules simply did not address whether the punter could recover the ball following a return kick.

So, after reviewing the rule book and noting that the return kicker was not prohibited from recovering the ball, the referee ruled that Fenton could recover the ball, so he awarded it to Stanford inside the 1-yard line. Cal continued to argue the call until Stanford's coach suggested they continue the game and refer the situation to the National Rules Committee, and Stanford would accept the ruling either way. Cal agreed to the suggestion, allowing the game to continue, and Stanford carried the ball over the goal line on the next play. With the score tied 5 to 5, Stanford converted the kick to take a 6 to 5 lead, which they held until time ran out.

The coaches then sent a telegraph describing the situation to Walter Camp, who agreed with the referee's ruling. Stanford was officially declared the winner of the biggest Little Big Game. It was an odd little situation that the rules committee soon clarified, so as Hamlet might have said to Horatio, "We shall not look upon its like again."

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to buy one of my books or otherwise support the site.

Bring it back!!!! If the NFL can take its liberties with the kickoff, why not? For that matter, why not provide a more rounded ball on demand, perhaps the only way to truly support the dropkick renaissance the game sorely needs?

I'll have to check how many onside punts and return kicks happen the next time I see a CFL game.