The First Iron Bowl and 1892-1893 Auburn Football Images

Earlier this year, I told the story of the goal after touchdown process in 1887 using a series of images taken during games at Harvard's Jarvis Field. Those images came courtesy of John Gennantonio, one of the top private collectors of 19th-century football images and miscellany.

Today, I have the opportunity to tell a story by sharing another five images from his collection. This time, the photos come from 1,200 miles south of Cambridge in Birmingham and Auburn, Alabama. Whereas the 1887 Harvard pictures reflected a football program that was 10+ years old, the Auburn images are from their first year playing football, when they played four games in the fall of 1892 and one in February 1893.

Football had primarily been a Northern game to that point. However, it was growing in the South, as one writer noted in an article previewing the first Auburn-Alabama game, which occurred in February 1893. Besides being the first Iron Bowl, it was also the first intercollegiate game in the state of Alabama.

Until recently the game was rarely played and little known in the South. In the last few years, however, all the leading Southern colleges have teams and football will be in the South as it is in the north, the leading collegiate game. Both the State institutions of Alabama (the Alabama Polytechnic Institute at Auburn and the University of Alabama at Tuskaloosa) have elevens this year and the two will meet and try conclusions in Birmingham February 22.

'That Great Game,' Advertiser (Montgomery), February 19, 1893.

Auburn had played only four games before meeting Alabama. They beat Georgia in February 1892 before winning 1 of 3 games played around Thanksgiving 1892:

2/20/92: Georgia @ Piedmont Park, Atlanta, 10-0 win

11/22/92: Duke @ Brisbane Park, Atlanta, 34-6 loss

11/23/92: North Carolina @ Brisbane Park, Atlanta, 64-0 loss

11/25/92: Georgia Tech @ Brisbane Park, Atlanta, 26-0 win

Alabama was also catching football fever, imitating the students at the colleges in the Northeast. Rather than play college teams, the pre-tidal Crimson played three games with teams from Birmingham:

11/11/92: Birmingham High @ Lakeview Park, Birmingham, 56-0 win

11/12/92: Birmingham Athletic Club @ Lakeview Park, Birmingham, 5-4 loss

12/10/92: Birmingham Athletic Club @ Lakeview Park, Birmingham, 14-0 win

After that, someone had the bright idea to schedule a game between Auburn and Alabama, which they planned for February. Both teams realized they had only a limited understanding of how to play the new game, so they looked for coaching assistance. Auburn sought help from Harvard, Yale, Princeton, and Penn, and Alabama likely did the same.

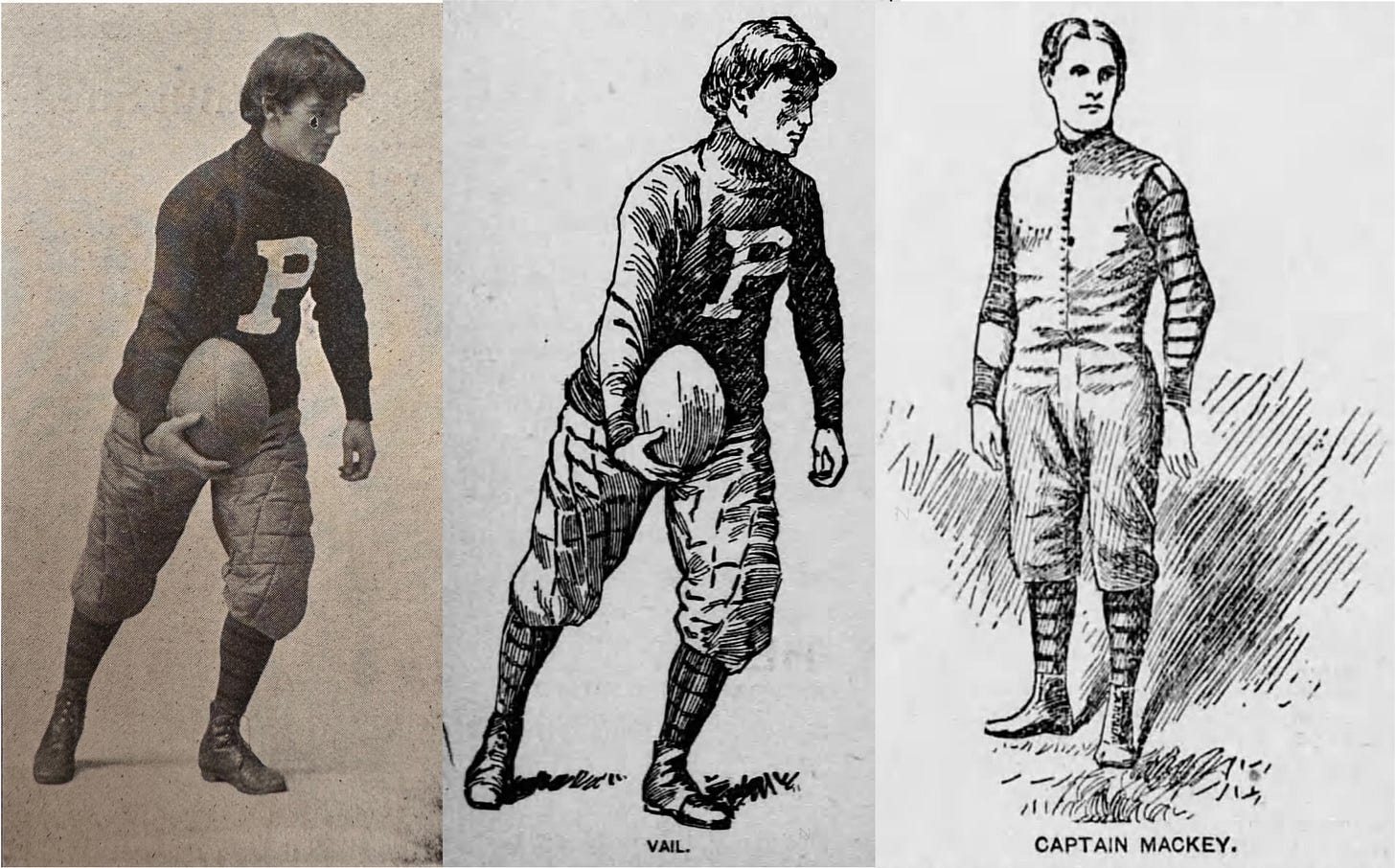

In early January, Louis Vail, Penn's quarterback, and Harry Mackey, Penn's left tackle and 1893 captain, visited Tuscaloosa, and Vail soon accepted the challenge of preparing Alabama for their game with Auburn.

Vail, who had a year of eligibility remaining, would have violated his amateur status by accepting payment for his coaching services, so he presumably volunteered for the role.

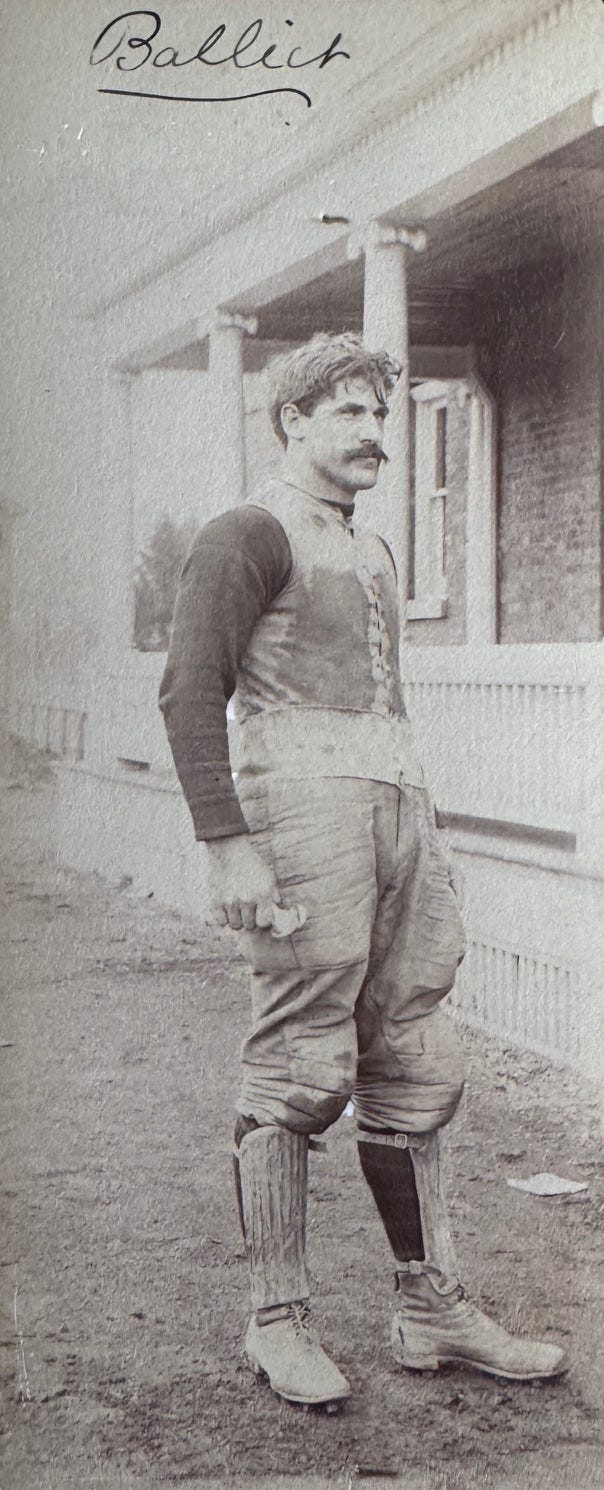

Auburn acquired the services of David M. Balliet, who played center for two years at Lehigh before transferring to Princeton for the 1892 season. Like Vail, he had another year of eligibility, so he, too, must have been a volunteer coach.

So, Auburn and Alabama acquired knowledgeable coaches from leading football-playing universities who could teach them the game’s best methods.

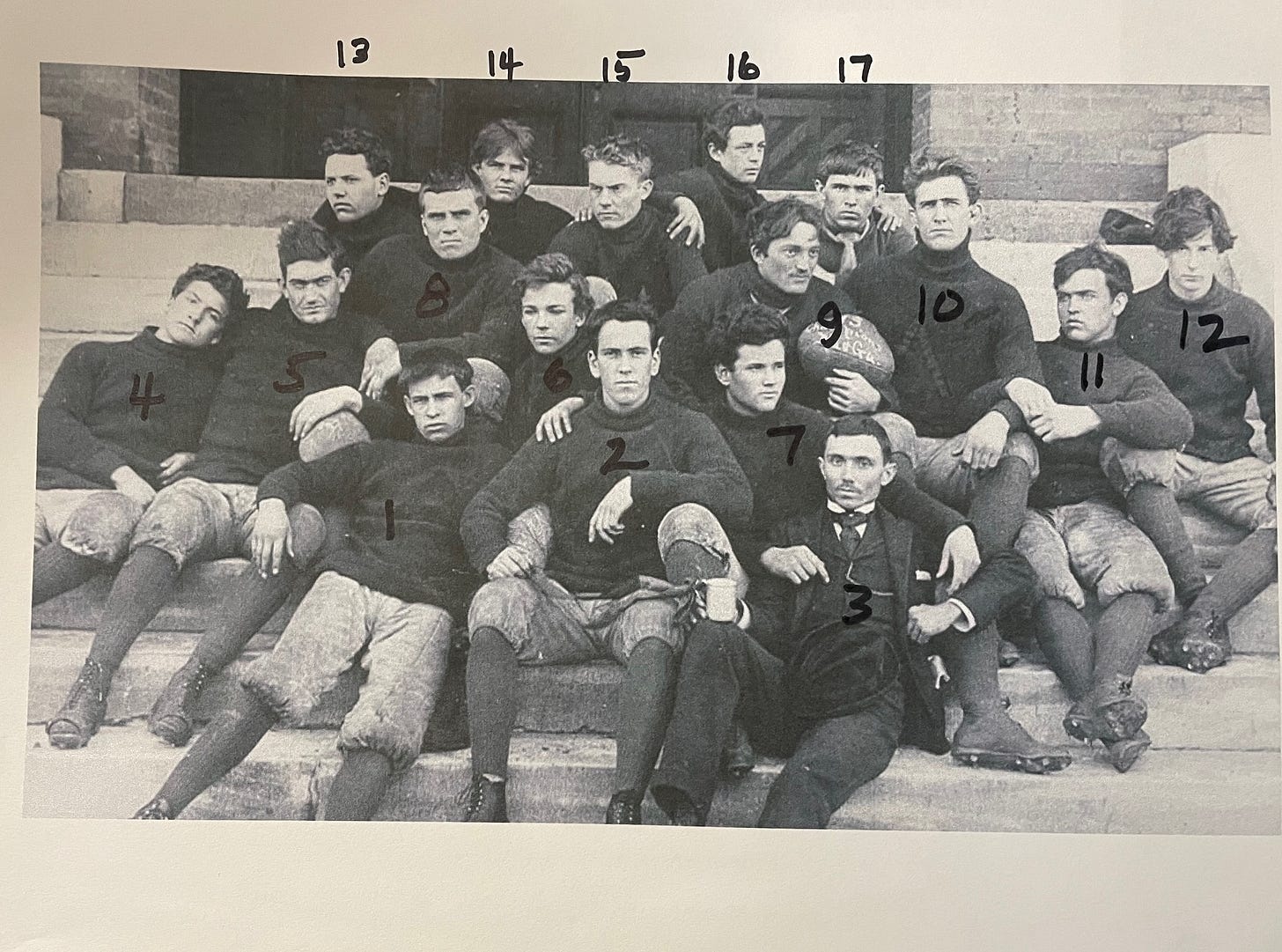

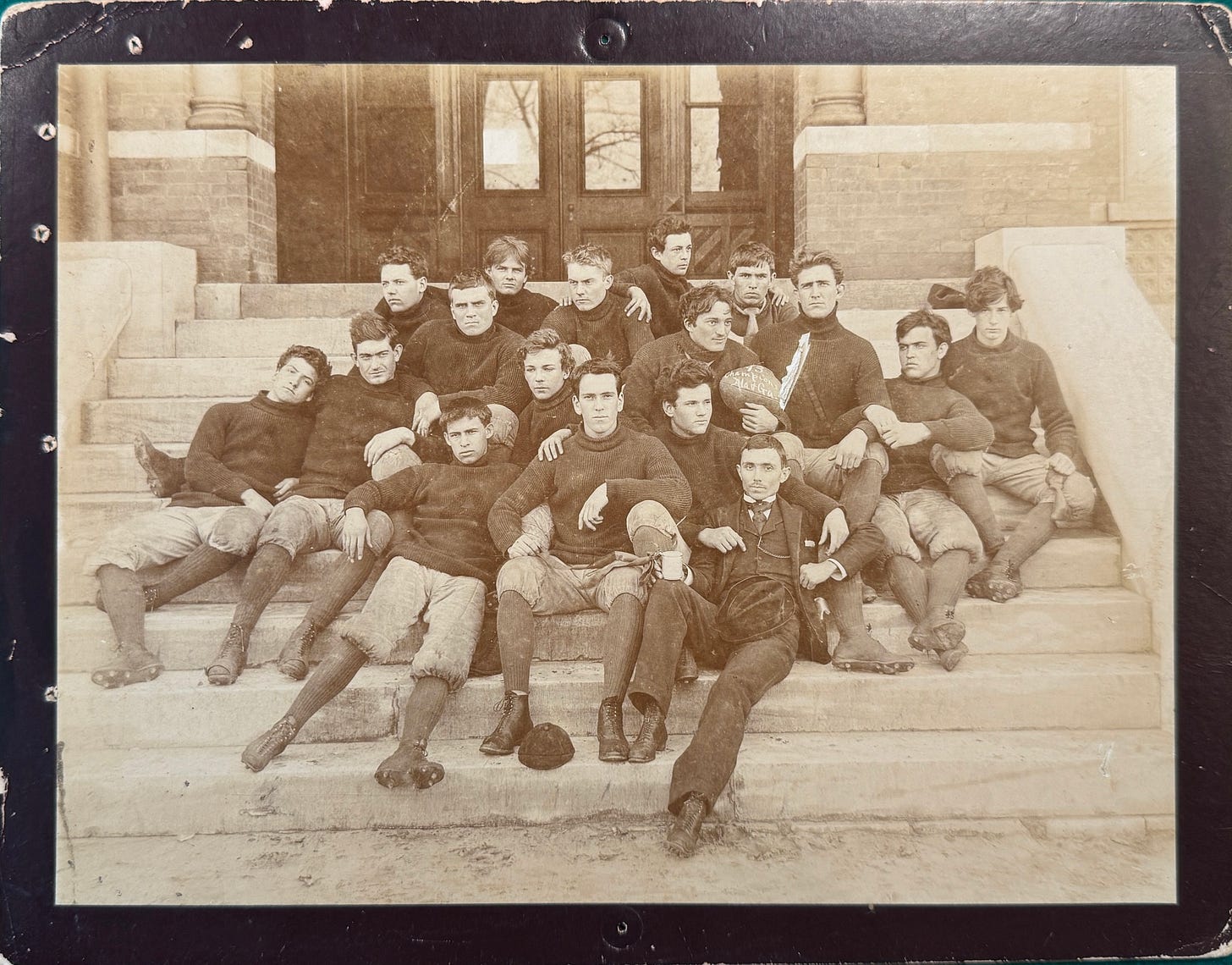

We’ll cover the game shortly but will “set the stage” by reviewing four posed photographs taken in the days following the game, which Auburn won. The first image in the collection shows the Auburn team posed on the steps of Samford Hall, Auburn's administrative building, when the school was still known as the Agriculture and Mechanical College of Alabama or Alabama Polytechnic Institute.

A tough-looking bunch of lads, two have nose guards hanging from their necks, a protective device invented by Harvard's captain, Arthur Cumnock, in 1892. Several have red As on their blue sweaters. The team manager holds a silver cup earned for their victory over Alabama, and team captain, Tom Daniels, holds a ball proclaiming Auburn the champions of Alabama and Georgia, based on their victories over Georgia and Georgia Tech in 1892 and the February 1893 victory over Alabama.

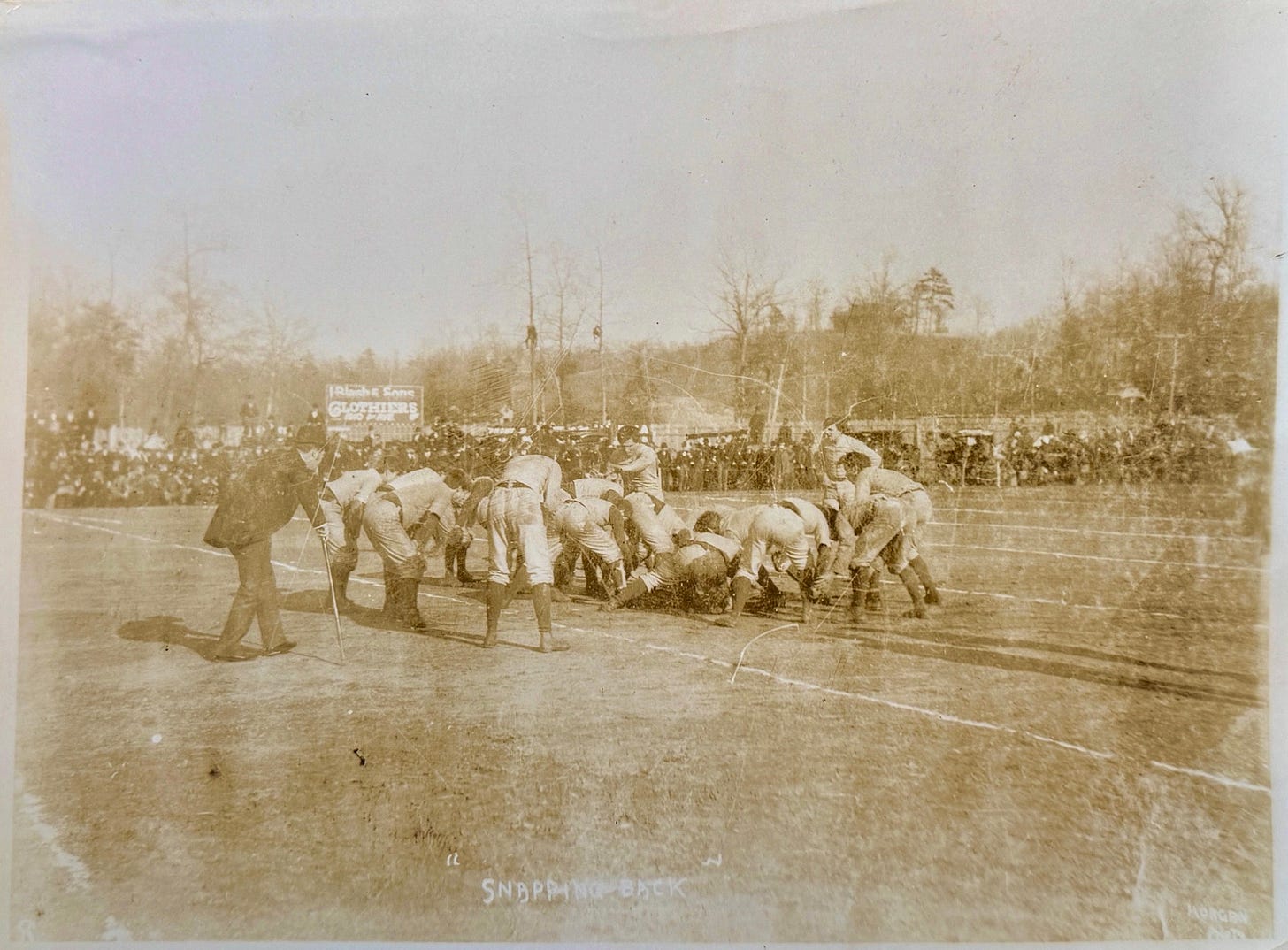

The second image shows the team aligned in the Traditional T formation in the field behind Samford Hall. Langdon Hall undergoes remodeling in the background. The left end, fullback, and right halfback wear nose guards. Everyone wears a canvas vest or jacket rather than their sweaters, as the center snaps the ball bearing the championship claim. The 1892 season was the first in which centers could legally snap the ball with their hands. Before that, they snapped with their feet.

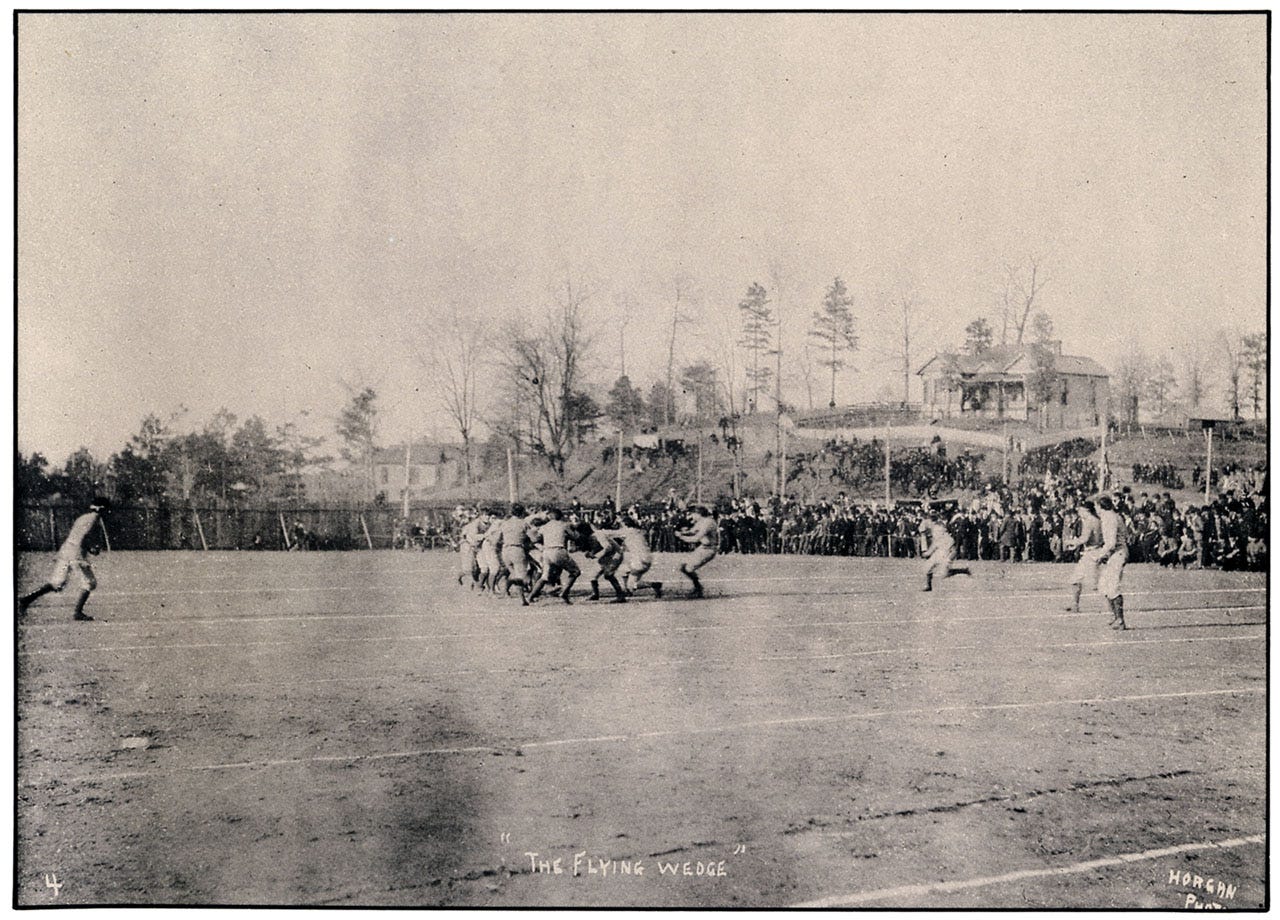

Auburn executes a Flying Wedge in the third image. Harvard unveiled the Flying Wedge against Yale in the last game of the 1892 season. (You can find a description of Harvard inventing and using the Flying Wedge here.)

Whereas today's communication technologies ensure that an innovative play or concept used in one part of the country is known everywhere else moments later, things were different in 1892. Teams learned of new plays through syndicated stories about the top Eastern teams that filled the pages of newspapers in small towns across the country. The newspapers publicized Harvard's execution of the Flying Wedge against Yale to sports fans nationwide, plus both teams had active Princeton or Penn players coaching them, so they had the inside scoop on how to execute the play. Both Auburn and Alabama regularly ran the Flying Wedge during their match, making them among the first teams in the country to run it. (News reports show Cal and Tulane ran the Flying Wedge in games on the same February day.)

As explained in more detail in the linked article, kicking teams of the era seldom kicked the ball far downfield to the return team. Instead, the often dribbled the ball a foot or two, picked it up, and ran forward with it. The Flying Wedge made that approach more effective by adding a phalanx in front of the ball carrier. In turn, since the kicking team ran with the ball rather than kicking it, the "return" team positioned most of their players close to the kicker to defend rather than return a kick.

That is the approach Auburn took in the image of their return team below. Like the image of the Flying Wedge, there are only ten players in this image; seven are within five yards of the imaginary limit line (midfield under today's rules).

Now moving to the Auburn-Alabama game, the fans and teams from each university arrived by train the morning of the game, then walked around town wearing ribbons with their school colors and offering their school yells, a practice Princeton introduced to college football in the 1870s. Auburn's cheer was:

Preck-a gegu, Preck-a-pegu,

Who wah, who wah,

Hallaboloo - Auburn!

'Auburn-Tuskaloosa,' Advertiser (Montgomery), February 18, 1893.

Alabama responded with:

Rah, Roo, Ree!

Uni-iversi-tie,

Rah, Hoo, Wah, Hoo.

'That Great Game,' Advertiser (Montgomery), February 19, 1893.

The game saw 5,000 people fill the grandstands and sidelines, and if outstanding defenses have marked the rivalry over the years, it did not start that way. Both teams moved the ball at will. Auburn formed a Flying Wedge on the opening kick, and after they scored the first touchdown, Alabama formed a Flying Wedge when it kicked off. With Flying Wedges used on nearly every kickoff, and both teams moving the ball easily, punts were few, leading a reporter who was new to the game to joke that football had as many kicks as baseball.

James Horgan, Jr., a noted photographer whose work documenting the South is held by prominent museums, took multiple images during the game, including one of a Flying Wedge in progress.

Of course, there were plenty of scrimmage plays, as seen in the fifth image from Gennantonio's collection, also taken by James Horgan, Jr. The opposing lines nearly overlap, there being no neutral zone at the time, and their uniforms shown in the sepia-toned photo make it difficult easy to tell one team from the other. However, the right offensive guard's stance matches the stance seen in the second posed image above, so Auburn is likely on offense.

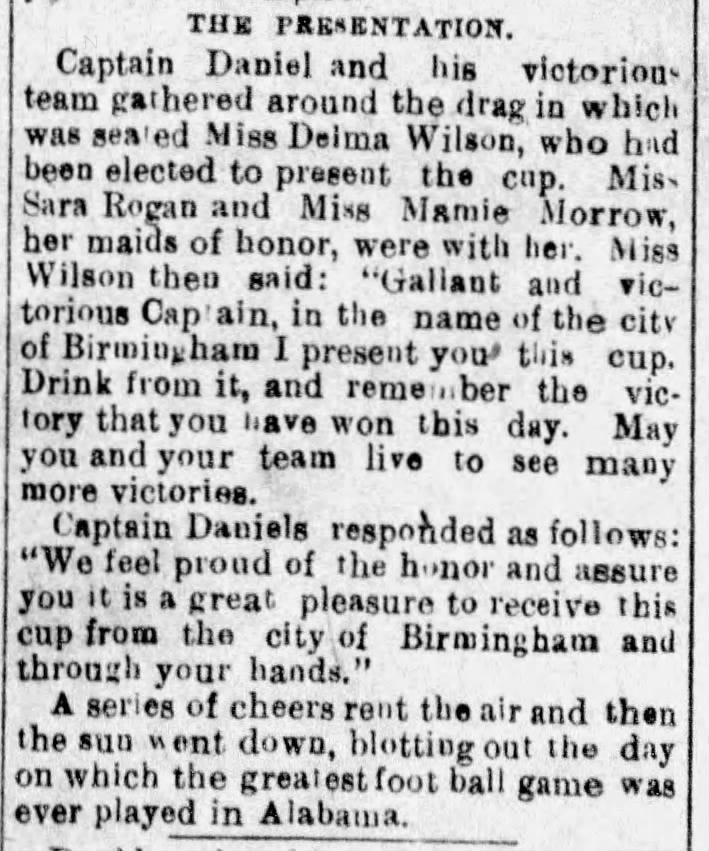

In the end, Auburn's fast-paced offense got the better of Alabama and they walked off the field with a 32-22 victory. As part of the post-game ceremony, Miss Delma Wilson presented Auburn's captain, Tom Daniels, with a silver cup to commemorate their victory.

Surely, the gallant and courageous Auburn men drank deeply from the silver cup and long remembered the victory won that day.

Original images, such as those shown above, are rare, particularly sets of images, and it is only through such images that we can confirm bits and pieces of how football operated 130+ years ago.

Thanks again to John Gennantonio for the opportunity to share these images with you.

Postscript

A reader, Booth Malone, corrected a few facts in the article and identified the players in the team picture. Each player’s corresponds to the name and position listed in the caption.

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to buy one of my books, donate, or otherwise support the site.

Daniels was Captain of the Auburn team that played and beat Alabama. See write-up in Birmingham News for 2-23-1893, pg 3.

Dorsey also played in that game. There are several good photos of him from his Auburn playing days. He was captain the next fall, Fall of 1893. There is a good recognizable image attached to his obit. I include here his senior (1894) photograph - if I am able to do it? - which is in the on-line digital collections of Auburn University. (See History of Auburn Univ.) I think its a match. If necessary can give you the name of everyone else in that team photo. But I'm not going to blow up your (excellent) site arguing about it.

Daniels' career at Auburn was brief, and I identify him in the Feb/Mar 1893 team photo, by process of elimination: he has the ball, and in Auburn team photos of that era, the captain (and only the captain) is always the one holding the ball.

I am writing an account of Auburn football of this era, so I've been diving deep - better to look at the 1890s than to keep seeing Auburn lose to Alabama in the 2020s.

Two corrections and a comment to the Alabama A&M team photo of 1893: Dutch Dorsey is not holding the ball. That is Tom Daniels the Fullback; Dorsey is the tough guy languishing next to the big man in the center of the bottom row. On the extreme right of the group, against the balustrade? is Walter Riggs, left end; he also sports a nose guard. Riggs graduated in '93, but played in '94 as a graduate student. He was team manager in the '95 season. With his Masters in Engineering he was hired by Clemson as a professor, then formed the first football team. In December 1899 Riggs hired Heisman away from Auburn to become coach. (Clemson and Auburn share similar team colors and a mascot, but Riggs allowed his alma mater to keep their cheers). Riggs became President of Clemson in 1911.