Goal After Touchdown Images from 1887

I wrote recently about potentially using AI-generated images to illustrate elements of early football for which photographs or drawings do not exist. Then, when working on the story about Jarvis Field, I stumbled across several images owned by a friend of games played at Jarvis Field in 1887. Three images show how Harvard executed goals after touchdown, a process akin to today's extra-point kick, in games against MIT and Wesleyan.

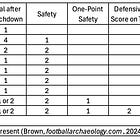

In 1887, field goals were worth 5 points, touchdowns were 4 points, and goals after touchdowns were 2 points. However, the goal after touchdown did not always occur directly in front of the goal posts like extra points do today. Instead, the kicking location depended on where the ball crossed the goal line on the touchdown play. Starting from that spot, the scoring team walked the ball onto the field in a line perpendicular to the goal line. They could walk the ball out any distance and attempt the kick from that spot.

Teams scoring near the goal posts had relatively easy kicks. At the same time, those scoring near the sidelines either walked a short distance onto the field and attempted the kick from an acute angle or walked it further to get a better angle, increasing the kick's distance.

Besides those options, the scoring team had two other alternatives. One, they could attempt a puntout. The TLDR version of that process is that the scoring team player punted the ball onto the field from where they crossed the goal line. If a teammate fair caught the punt, they could attempt the kick from that spot.

The second alternative was to walk the ball out as described earlier and deliberately miss the kick, a tactic Walter Camp claimed as a Yale invention. Dribble kicking was common then. Teams kicking off regularly dribbled the ball, much like at the start of a soccer match. The kicker booted the ball a few feet, picked it up, and ran with it. Harvard modified the dribble kick to create the flying wedge in 1892, which was effectively banned in 1894 by requiring kickoffs to travel at least 10 yards.

Following the same logic but applying it to the goal after the touchdown, Yale dribble-kicked the goal after the touchdown attempt, picked it up, and ran with it. If they scored a touchdown on the play, they earned another four points and had the opportunity for another kick. If they did not score, the kicking team retained possession and had a first down wherever the dribble kick play ended.

While I have been aware of the dribble-kick approach for some time, I never thought about how the kicking or defending teams might align in those situations and, more generally, how they aligned for any goal after a touchdown attempt in an era when the missed kick was a live ball.

I started this story by mentioning a series of photos of Harvard playing in 1887. Three of those photos show Harvard kicking goals after touchdowns. All three images show kicks attempted directly in front of the goalposts, so Harvard must have scored their touchdowns by crossing the goal line between the goal posts. (The images clearly show goal after touchdown attempts because field goals were contested kicks from scrimmage, all of which occurred by drop kick at the time.)

The first image label reads: "Saxe kicking a goal, Harvard-Tech - October 15, 1887. James Alfred Saxe played for Wesleyan before joining Harvard's 1887 and 1889 teams. Saxe is seen kicking during the MIT game.

The image shows the kicking team stretched out across the field as we do on kickoffs today. While Harvard appears to have tried to make each kick attempt rather than dribble kick, a missed kick was a live ball, so spreading the kicking team's players across the field protected against a defense recovering the missed kick and running the ball back. Likewise, the defenders are stretched out across the field since they had to protect against the kicking team recovering a missed kick behind the goal line for a touchdown.

You also see the holder lying on his stomach, having held the ball using the over-under technique, while the defenders closest to the kicker try to block the kick. (On the free kick, the defense had to be behind the goal line and could rush as soon as the holder placed the ball on the ground.)

The second image shows another kick directly in front of the goal posts. As in the first image, the holder is on his stomach, and the referee stands next to him to judge whether the kick is good. However, this image shows defenders standing 15 to 20 yards behind the goal posts because football did not yet have end lines or defined end zones, so the ball remained live regardless of how far it sailed. (Canadian football teams generally position a returner behind the goal line due to their rouge.)

Since the ball was live, missed kicks recovered by the defense could be run back, return kicked (immediately punting the ball back to the kicking team), or downed behind the goal line. If they downed the ball, the defenders then executed a kickout, meaning they kicked the ball from their 25-yard line to the team that scored the touchdown. A descendant of this process remains in American football today in the procedure that follows safeties.

The third image is much like the second, though a few Harvard players and another official or two are standing behind the kicker.

Walter Camp argued against the dribble kick process in 1887 because it did not promote open football, and powerful teams sometimes used it to dominate the less fortunate. Harvard beat MIT 62-0 and Wesleyan 110-0 in 1887, though the newspaper accounts do not mention whether Harvard dribbled kicked on the goals after touchdown. The images suggest they tried to make each kick.

The football community finally agreed with Camp in 1891 and changed the rule. From then on, missed goal after touchdown attempts resulted in a dead ball, so conversion kicks in American football are no longer as exciting as they once were, while our Canadian neighbors get to have more fun.

After missed kicks became dead, defenses concentrated themselves in front of the kicker in an attempt to block the kick, while the offensive players other than the holder and kicker rested behind the kicker or near their bench.

The three 1887 Harvard images in this story are the only examples I recall seeing of the goal after touchdown process before 1891. Without university archives and individual collectors who preserve these artifacts and make them available for public consumption, we would lose our ability to understand how the game worked in the past and how it evolved to the present. So, hats off to those who save these beautiful images and share them with others.

Click Support Football Archaeology for options to support this site beyond a free subscription.

Great stuff!