Today's Tidbit... As The Quakers Go Rolling Along

A few days ago, I wrote about the 1902 Rose Bowl and how it was viewed for nearly forty years as a one-off game, unconnected to the Rose Bowl contests that began in 1916. Before and after 1916, football teams from northern climes periodically traveled to fair-weather locations for a game or three over the holidays. These games began when Chicago visited the West Coast in 1894, continued with a Yale Consolidated team going South in 1896, and through to the San Diego Christmas Classic in 1921 and 1922. More generally, a mishmash of late-season and one-off holiday games helped prepare us for the college bowl system to come.

Despite attempts by other cities, Pasadena's Rose Bowl and San Francisco's East-West Shrine Bowl were the only bowl games of note until the mid-1930s. So it was under those conditions that the University of Pennsylvania Quakers set off to play California in a one-off game on New Year's Eve in 1927. The game honored the memory of Andy Smith, who played at Penn before the forward pass and coached the Quakers for a few years before making his way to Berkeley, where he restarted the football program in 1916. Over the next ten years, he went 74-16-7, winning four national championships with his Wonder Teams.

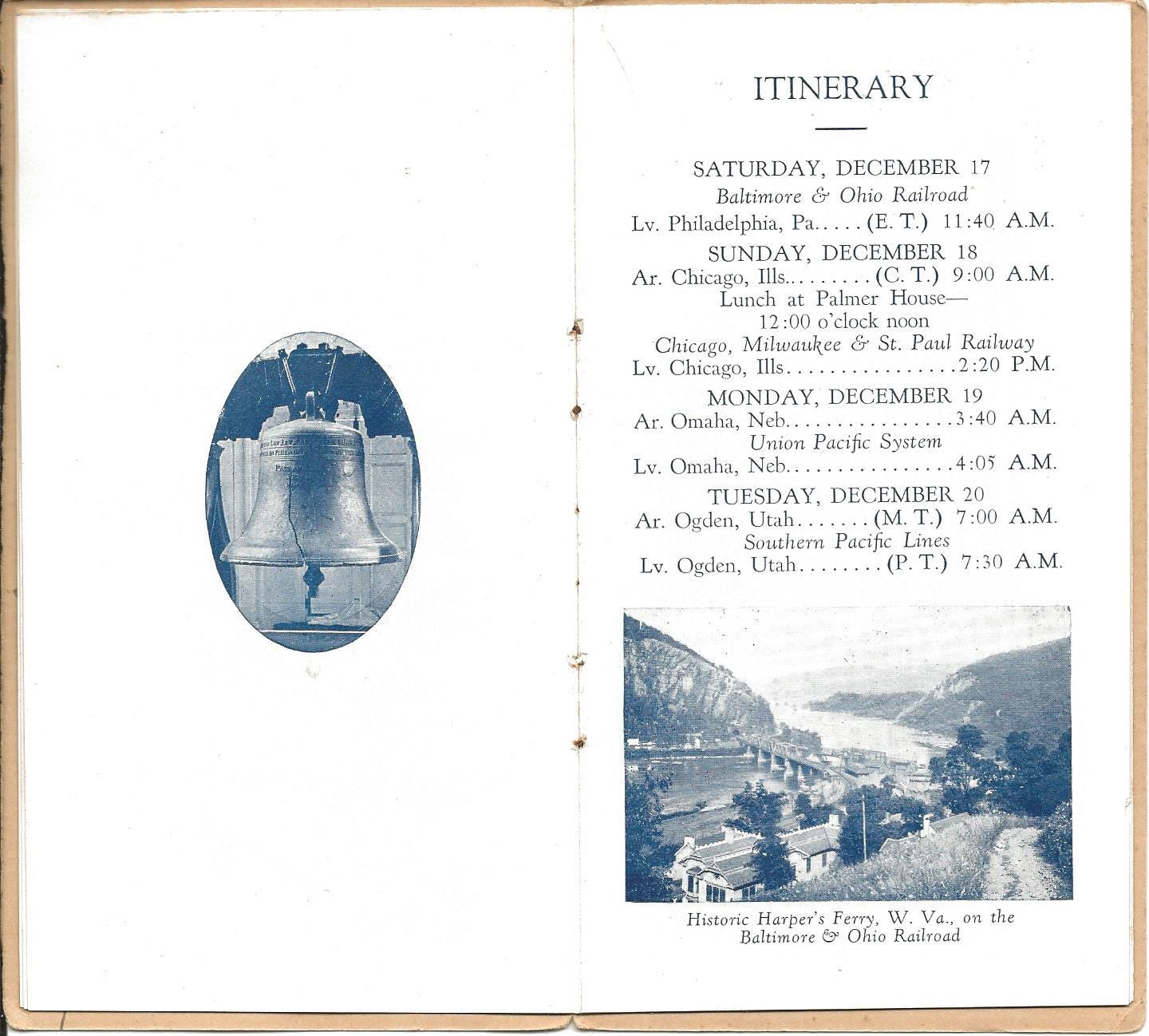

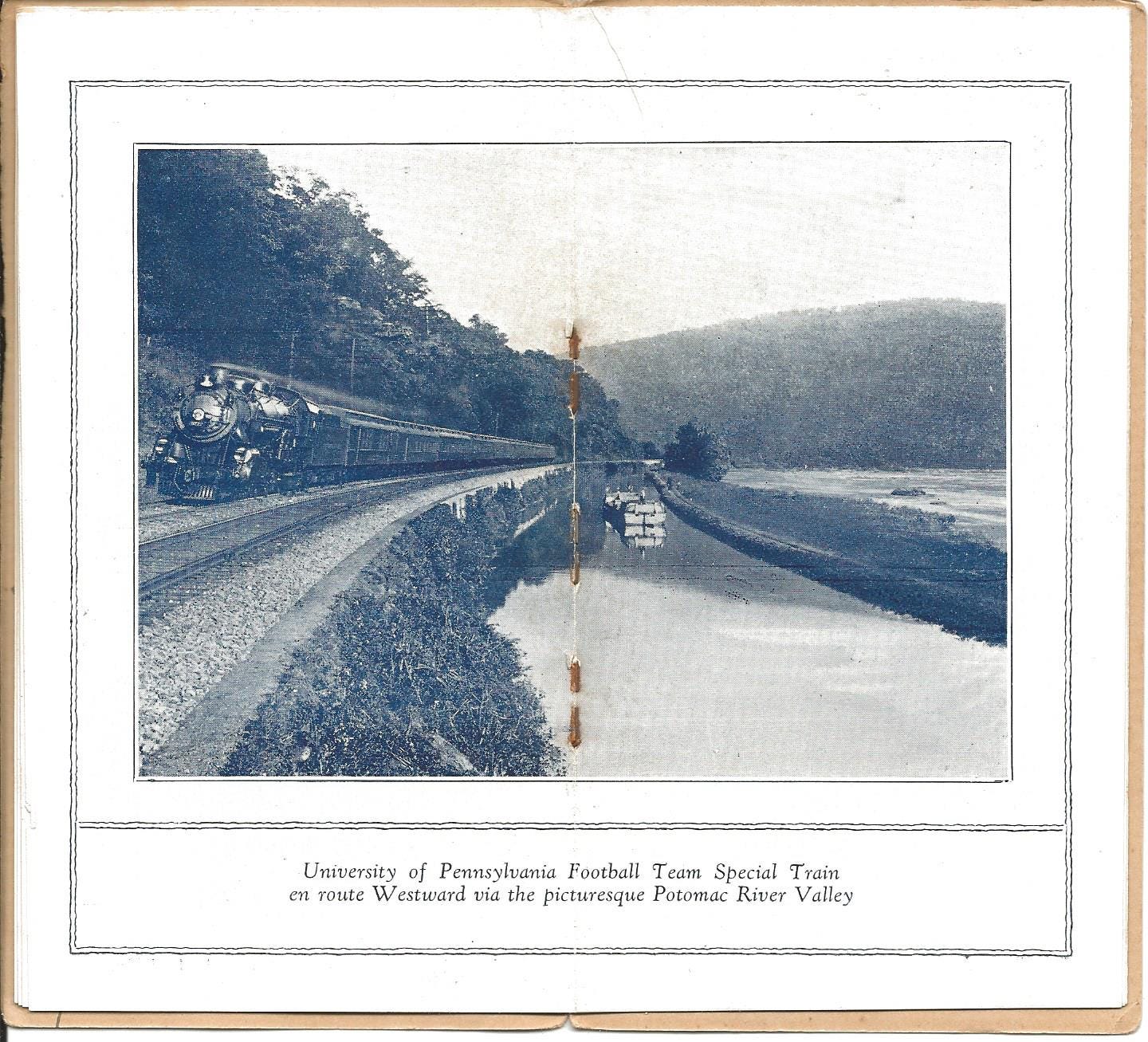

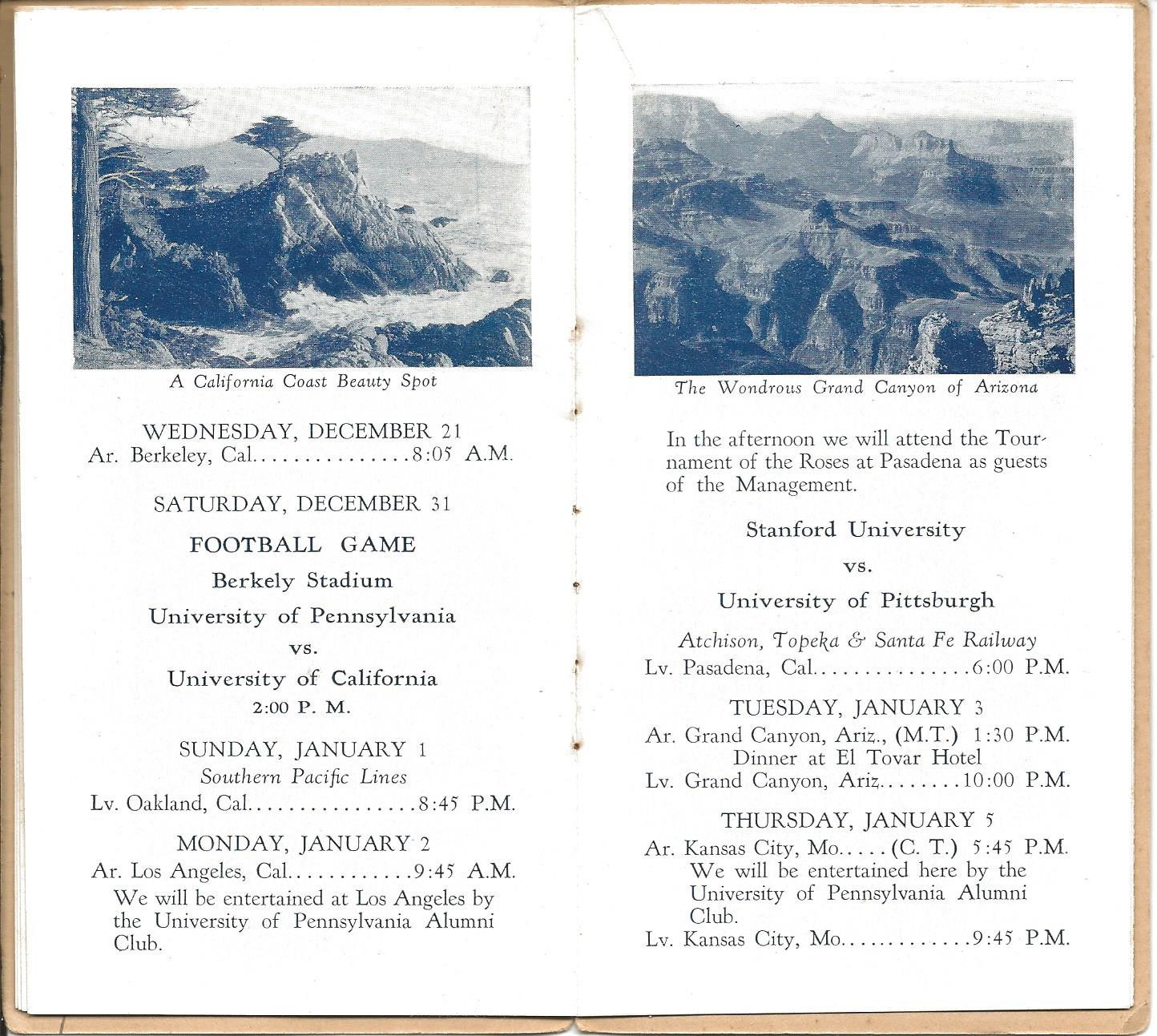

Penn, which then led the college football world in attendance year after year, was heading west for the third time. They lost to Oregon 14-0 in the 1920 Rose Bowl and went down to Cal 14-0 on New Year's Day 1924, but they learned their lesson in '24 when they traveled across the country by train and arrived in Berkeley only two days before the game. This time, they left Philadelphia on December 17 and arrived in Berkeley on the 21st, giving them ten days to practice and acclimate before facing the Bears in a Saturday night game. After the game, they would head south to Pasadena to attend the 1928 Rose Bowl, played on Monday since New Year's Day fell on Sunday.

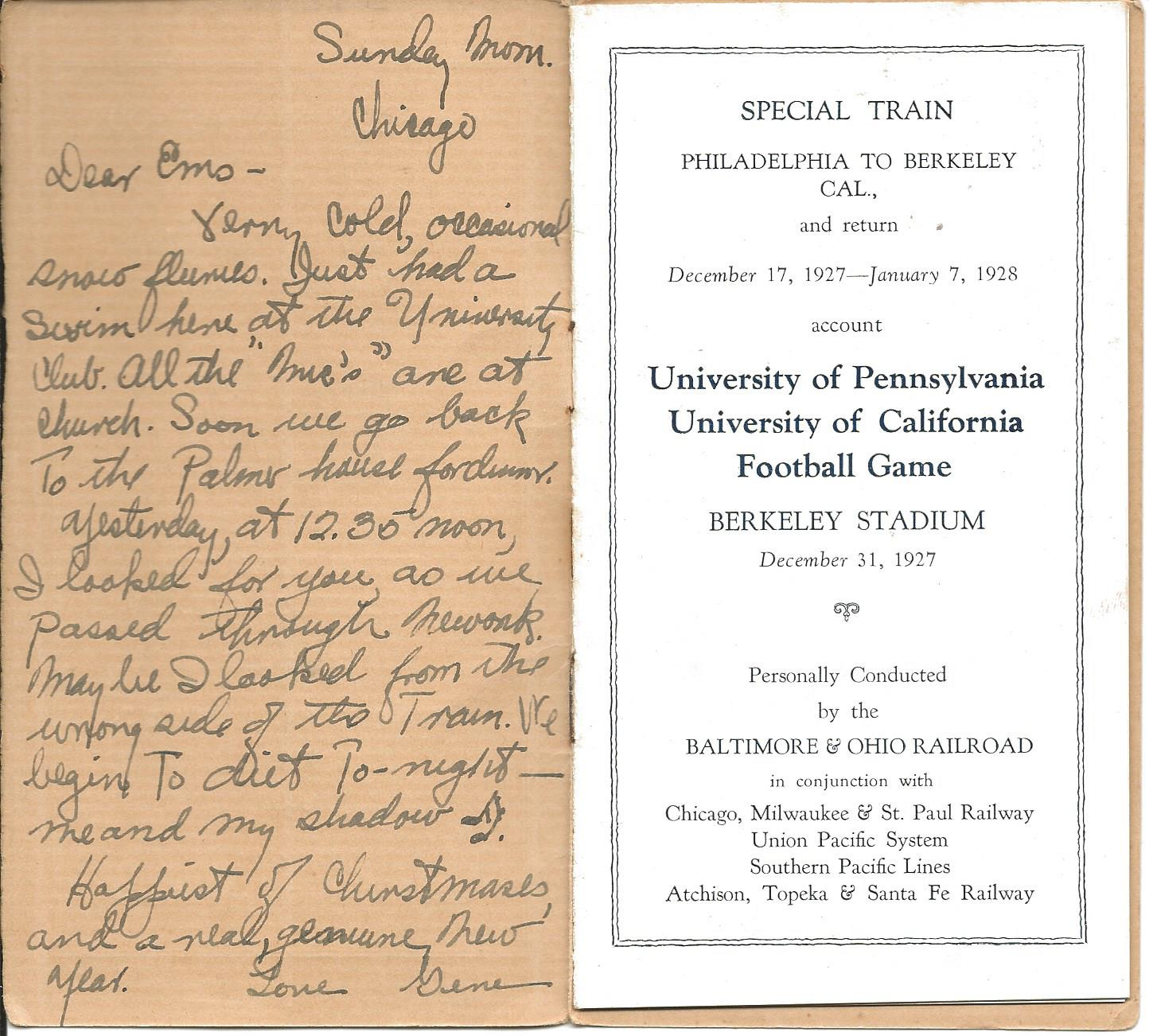

Penn's three-week trip, which included stops and activities along the way, was laid out in a handy itinerary.

This particular copy of the itinerary likely belonged to S. Eugene Kuen, Jr. '30, a backup tackle on the 1927 team. His note, written in Chicago after the first night of travel, mentions his “Mc” teammates going to church that morning. Such were the times.

After lunch at the Palmer House, they switched railroads for the first of several times and continued west.

Despite the excitement of the postseason game, it had been a disappointing season for the Quakers. They allowed only six points total in their six wins but lost three in a row midway through the season to Penn State, Chicago, and Navy. Still, they ended the regular season beating Harvard 24-0, Columbia 27-0, and Cornell 35-0, so they were optimistic as they road into the setting sun.

Cal also entered the game 6-3, losing three of its last four, with those losses coming against the best teams on their schedule: USC, Washington, and Stanford. The dope said the Quakers were two-touchdown favorites, and as the only football game of note that week, the game’s play-by-play would be available on radio nationwide.

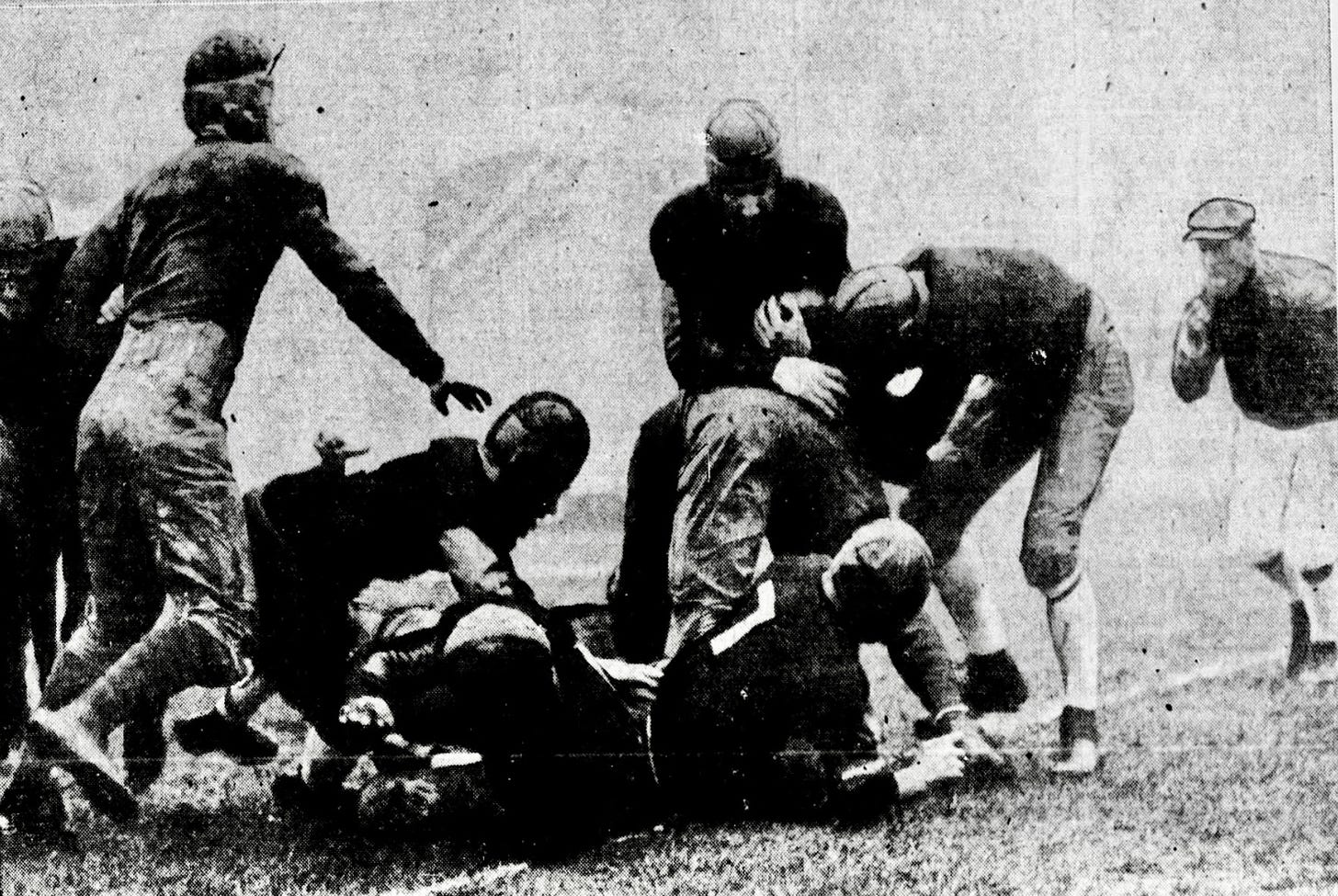

The game proved to be a tight battle, at least for three quarters. Cal threw a 41-year touchdown pass four minutes into the game, but Penn soon scored on a pick-six, missing the extra point. Penn then pounded the ball up the middle on a long drive culminating in a second touchdown and a 13-7 halftime lead. Unfortunately, that ended the Quakers’ scoring for the day since the Bears intercepted six of the eleven Quaker passes. Despite recovering two Cal fumbles, the turnovers proved too much. With the score tied at the end of three, Cal's Brick Marcus ran 55 yards for a TD early in the fourth quarter and later swept wide for a second touchdown to seal the game as Cal won 27-13.

Following their trip to LA and the Rose Bowl, the Quakers entrained on January 3rd to return to Philadelphia, stopping to gape at the Grand Canyon and earning a meal in Kansas City.

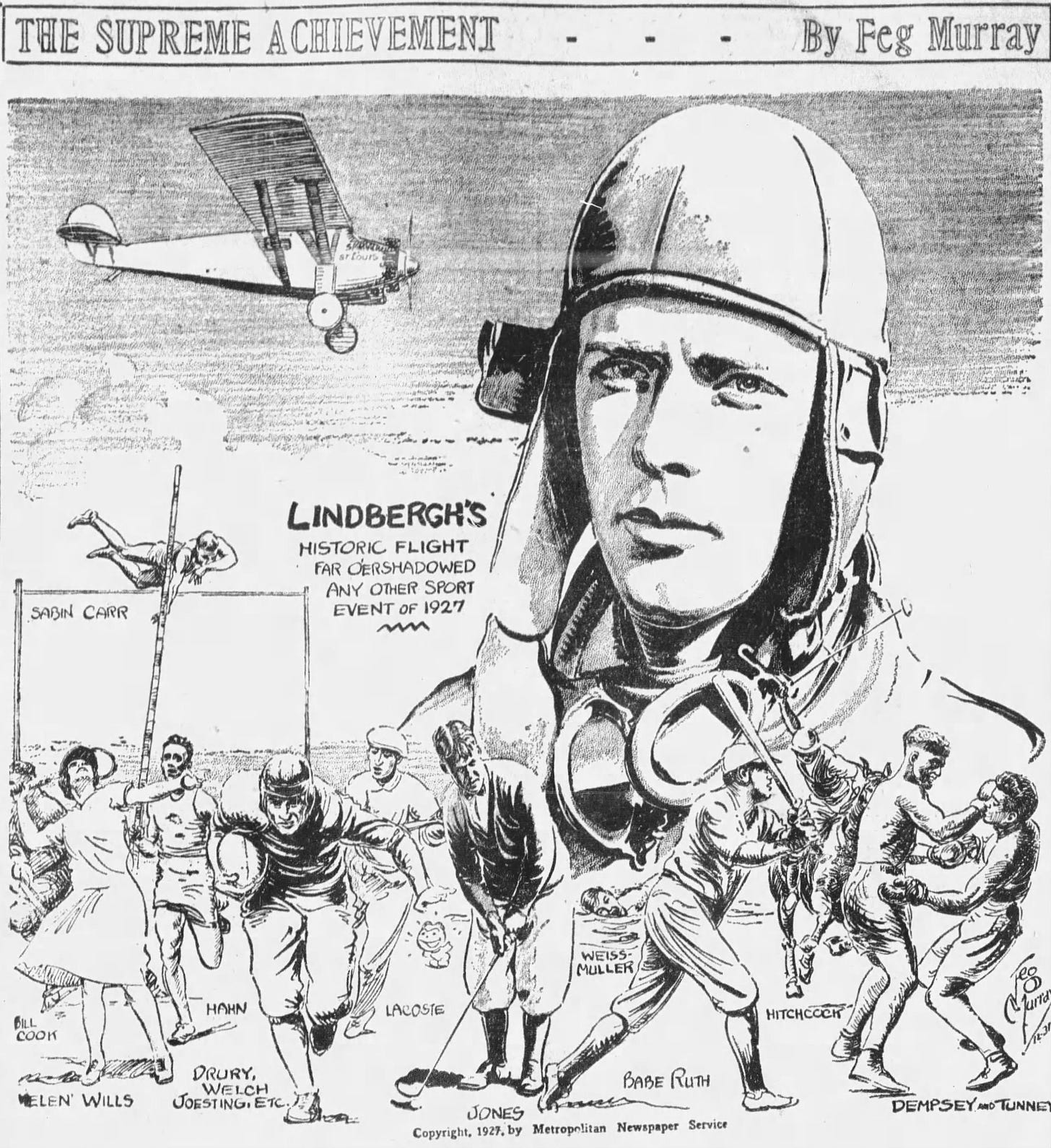

Despite having played in the second biggest game of the holiday season that year, the New Year's Day copy of the Los Angeles Times made it clear that neither their game nor any other sporting event of 1927 held a candle to the trick pulled off by Lucky Lindy. His flight foreshadowed the advances in aviation that would allow future teams to fly between the East and West regularly and do so in one day. That future arrived two decades later when a few college teams, the Los Angeles Rams and the San Francisco 49ers, made travel by football teams between the East and West commonplace.

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to buy one of my books or otherwise support the site.

Ruth's longest home run was 575 feet. Lindbergh's flight was 3,600 miles, thought I understand he could never hit the curveball.

Great post! Babe Ruth's record held up longer than Lucky Lindy's...just sayin'!