Today's Tidbit... A History of Football Tees

My desire to write this post was spurred by buying the RPPC below, which shows Felix La Force, the captain, fullback, and kicker for Hamilton College, in 1914. It is an unremarkable image other than it clearly shows a kicker teeing up the football on a dirt mound or tee. I have other photos of kickers and dirt tees, but this is the best I've come across.

I’ve written about the kicking game in the past, plus stories about punting, but no previous story covers the evolution of the lowly tee.

As described in the first linked article, early golfers started each hole by placing the ball on sand mounds built within an imaginary circle one club length's distance from the previous hole. The Scottish Gaelic word for circle is taigh. When the damn Brits Anglicized it, they called them tees.

Like rugby, some football kickers depended on teammates to hold or place the ball. Others set the ball in a divot made with the heel, while others set it on a mound of sand or dirt they sculpted at the spot of the kick. Kickers even kept buckets of sand or dirt on the sideline to facilitate building their mounds, a process that took time. Of course, that all happened before the rules specified the number of seconds teams could take between plays, so referees let the mound builders take the time to build a mound and tee the ball, even as the clock ticked.

Things began changing in 1916 when Auburn's Moon Ducote kicked a 40-yard field goal against Georgia. Rather than build a tee, Ducote kicked the ball off his holder's floppy helmet, which the holder placed on the ground. Similarly, Amos Alonzo Stagg claimed Wisconsin stocked baked clay tees on the sideline for use by their kickers. Neither seemed fair, so the Rules Committee banned artificial tees in 1917. Then, with the onset of huddling, game officials became more watchful of stalling, and arguments ensued. In 1924, the rules banned all tees, and holders returned to their former duties.

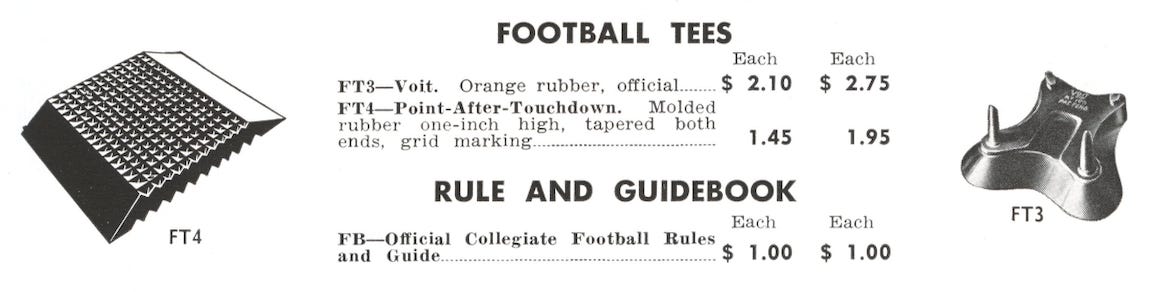

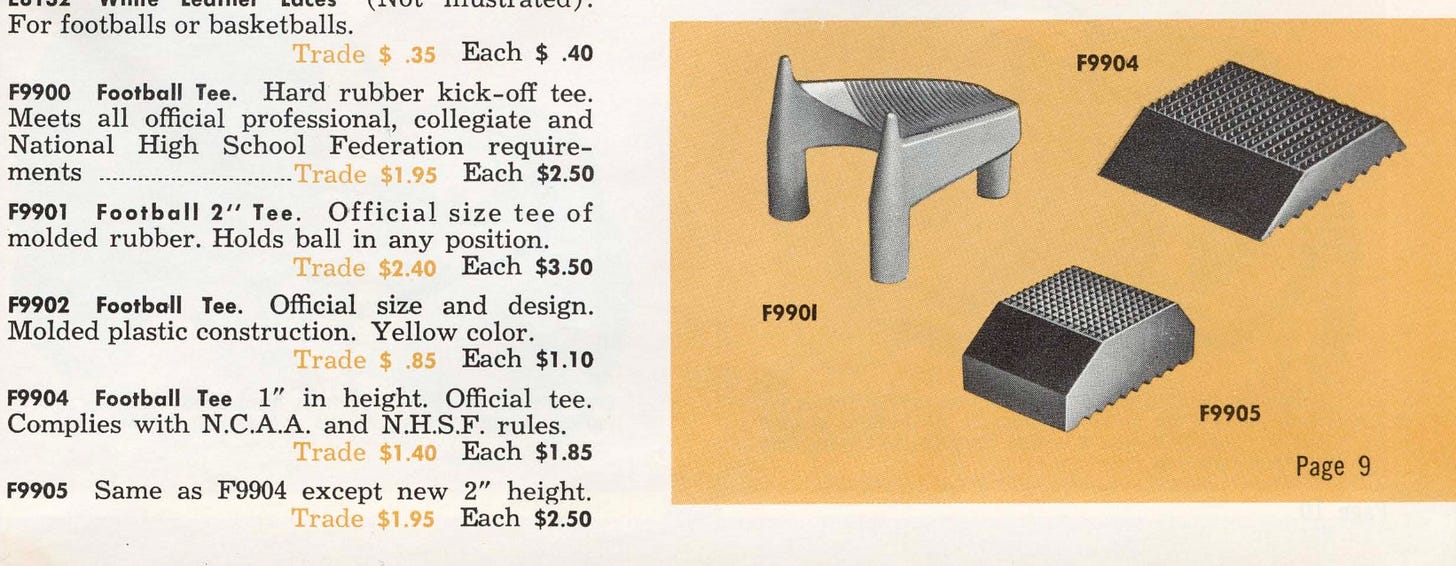

The NFL allowed tees again in 1941, and the NCAA followed suit in 1948. Those changes sent the world's inventors into their workshops to create a variety of tees. The catalogs of 1949 included two fundamental designs; one or the other has dominated the market ever since. One design has the ball rest against pegs, while the other has the ball's tip rest in a dimple, divot, or hole.

The FT model above took the dimpled approach and appears the same as model 571 below. The Cherberg model follows the same general plan but is deep enough to form a divot or hole. Incidentally, the Cherberg tee is named after then-Washington Husky assistant and later Washington head coach John Cherberg.

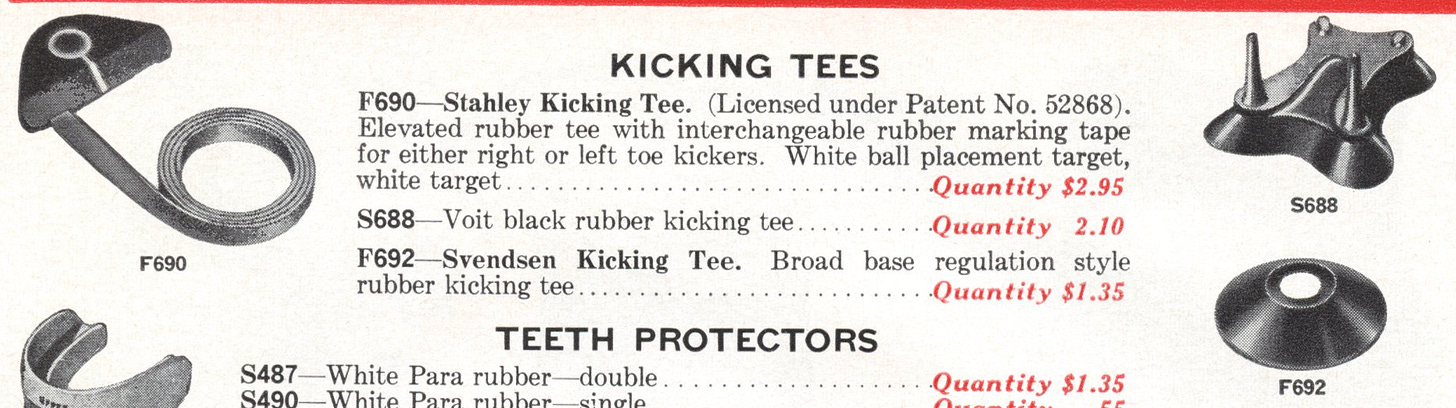

Then came the Stahley kicking tee, invented by Skip Stahley, who happened to be on Washington's staff with fellow assistant John Cherberg. Made famous through its use by Lou "The Toe" Groza, the Stahley tee had an attached tape that kickers stretched out to help them aim. The NFL and NCAA soon banned aiming devices from games, but they stuck around on practice fields for some time. (Some mound builders also spread a trail of sand or dirt behind their mounds to improve their aim.)

The tee shown so far were used for kicking off. Tees or blocks used for field goals and PATs were not much of a thing because teams attempted and made few field goals in the 1940s and 1950s. (Only 108 field goals were made among all NCAA University Division kickers in 1958, leading to a widening of the goal posts in 1959 to increase scoring.) Based on the catalogs I own, the PAT tee or block first appeared in 1955. Like the kickoff tee, it raised the ball one inch off the ground.

A strapless variation on the aiming device tee for PATs and field goals appeared in 1955 as well in the form of the “Bootin’ Ben” kicking tee, which must have helped an aimless kicker or two.

The divot-style tees disappeared from the market by the early 1960s and the kickoff tee evolved into a two-peg “Boomer” version with ball held in place by the textured surface rather than small front pegs. In addition, the NCAA approved two-inch tees and blocks in 1965, allowing kicks to sail higher with improved hang time.

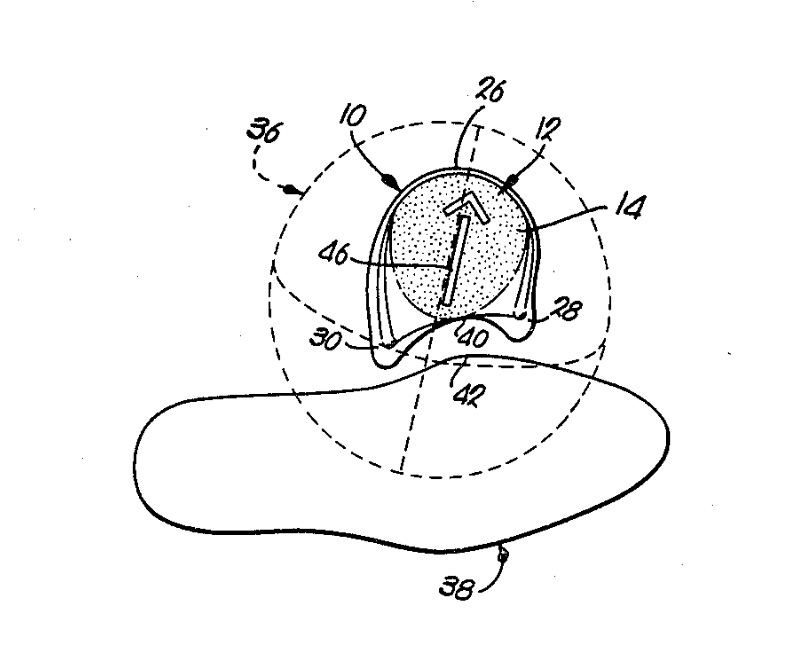

Of course, the tees shown previously were for straight-ahead or conventional kickers. Soccer-style kickers arrived in numbers in the 1960s and especially the 1970s, but they continued using tees designed for conventional kickers until 1983 when Jan Stenerud patented his Sidewinder kickoff tee. It repositioned the prongs, so the kicker's foot struck the ball before the prong. The Sidewinder design required right- and left-footed versions.

Soccer-style kickers proved so successful kicking from the two-inch block that the NCAA banned kicking blocks entirely in 1989. (One and two-inch blocks remain legal at the high school level.)

While the three-pronger tee remains popular in American football, at least based on the number on the market, kickers at higher levels of football use the Ground Zero model. Invented by a former Cornell straight-ahead kicker, Ground Zero's marketing folks claim its tee has seen action on the opening kick of every NFL game since 1999. The Ground Zero's textured design keeps the ball steady, while the absence of prongs allows kickers to strike the ball cleanly regardless of their technique. Some models have a notch in front for placing the ball when onside kicking.

In 2006, the NCAA reduced the height of kickoff tees from two inches to one to limit the number of touchbacks and reduce the dead time in games for television purposes.

That may be more than you ever wanted to know about tees and blocks, but I’m sure some readers got a kick out of this story.

Notice: FootballArchaeology is not subject to Trump’s idiotic tariffs, so the $50 annual subscription is still just $50.

Click Support Football Archaeology for options to support this site beyond a free subscription.

I was a kicker in High School...when talk of the kick-off being eliminated started to become more serious I decided to start collecting kicking tees (and blocks)...In my research the acceptable height was once up-to 3" (not sure at what level/league)...I only have a 3" Stenerud tee...the rest are 2" or less...studying Product Design in college I was always fascinated by various approaches to creating "a chair" for a football. Loved the article...the Stahley design was new to me!

Has a golf tee--perhaps an enhanced model--ever been used/tried? ..