Today's Tidbit... Harvard Stadium's 1929 Expansion Plans

Being the first out of the gate confers advantages and disadvantages, especially when it comes to football stadiums. Harvard Stadium was the world's first large reinforced concrete structure, and its pioneering design meant its construction in 1903 garnered global media attention. It featured many elements that became norms for the stadiums that followed, yet Harvard Stadium lacked locker rooms, restrooms, concessions, and a press box. Additionally, spectators sat directly on the stadium's concrete slabs rather than on benches, so fans brought blankets or cushions on cold days.

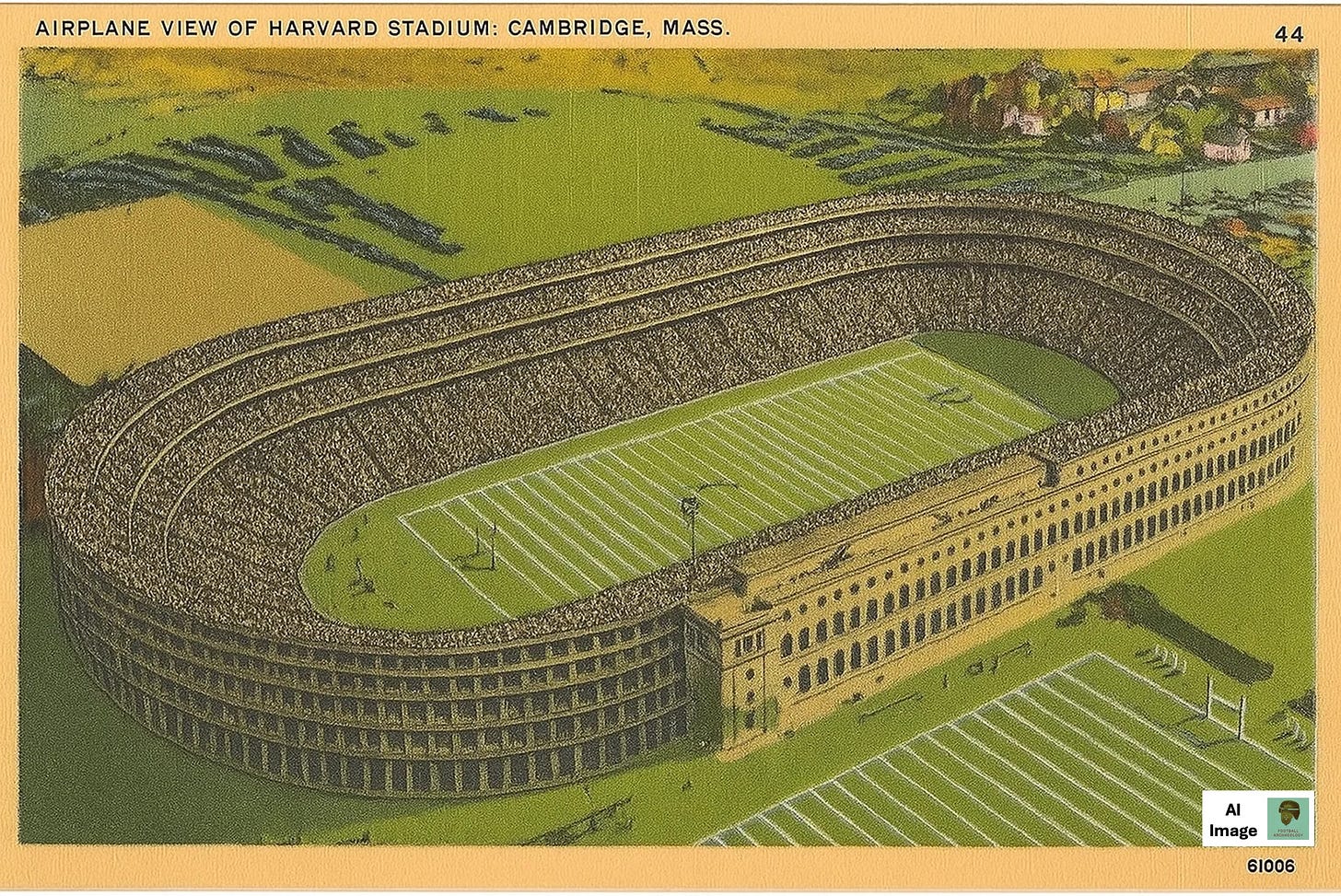

Harvard Stadium had a capacity of 27,000 when it opened. Temporary seating along the track and at the open end of the U-shaped stadium extended the capacity, and additional seats came along when they built the colonnade atop the stadium in 1910.

Syracuse built its concrete Colossus a few years after Harvard. Then 1914 brought Princeton's Palmer Stadium and Yale's big bowl, tapping in at 70,896 seats. Things worsened with the arrival of the Boomers. I'm not referring to the Boomer generation, born between 1946 and 1964. Instead, the Boomers were the massive, modern football stadiums built across the country in the 1920s. Many of those remain with us today, with more than 40% of Power 4 stadiums dating to that period.

By the late 1920s, Harvard Stadium began showing its age. It handled 30,000 fans in permanent seats and another 27,000 or so in temporary wooden bleachers or SRO when bursting at the seams. The stadium's capacity meant that 13,000 more Yale alums could see a Harvard-Yale game in the Yale Bowl than Harvard alums could at Harvard Stadium. That did not sit well with many Crimson alums, of which there were 48,000 who had yet to breathe their last.

A one-minute video below features scenes from the 1927 Harvard-Yale game and offers a glimpse of the temporary seats located immediately below the grandstand.

The seating limitations were exacerbated by the ticket allocation system, which restricted the number of seats allocated to alums. In 1928, Yale received 40% of the tickets for the Harvard-Yale game. The remaining 60% went to:

Coaches and freshmen athletes

Graduate and undergraduate Varsity Club members

Members of the sophomore, junior, and senior classes

Members of the Class of 1903, celebrating their 25th year post-Harvard

Faculty members, graduate students, and others

Alums requesting only one seat

Alums requesting more than one seat

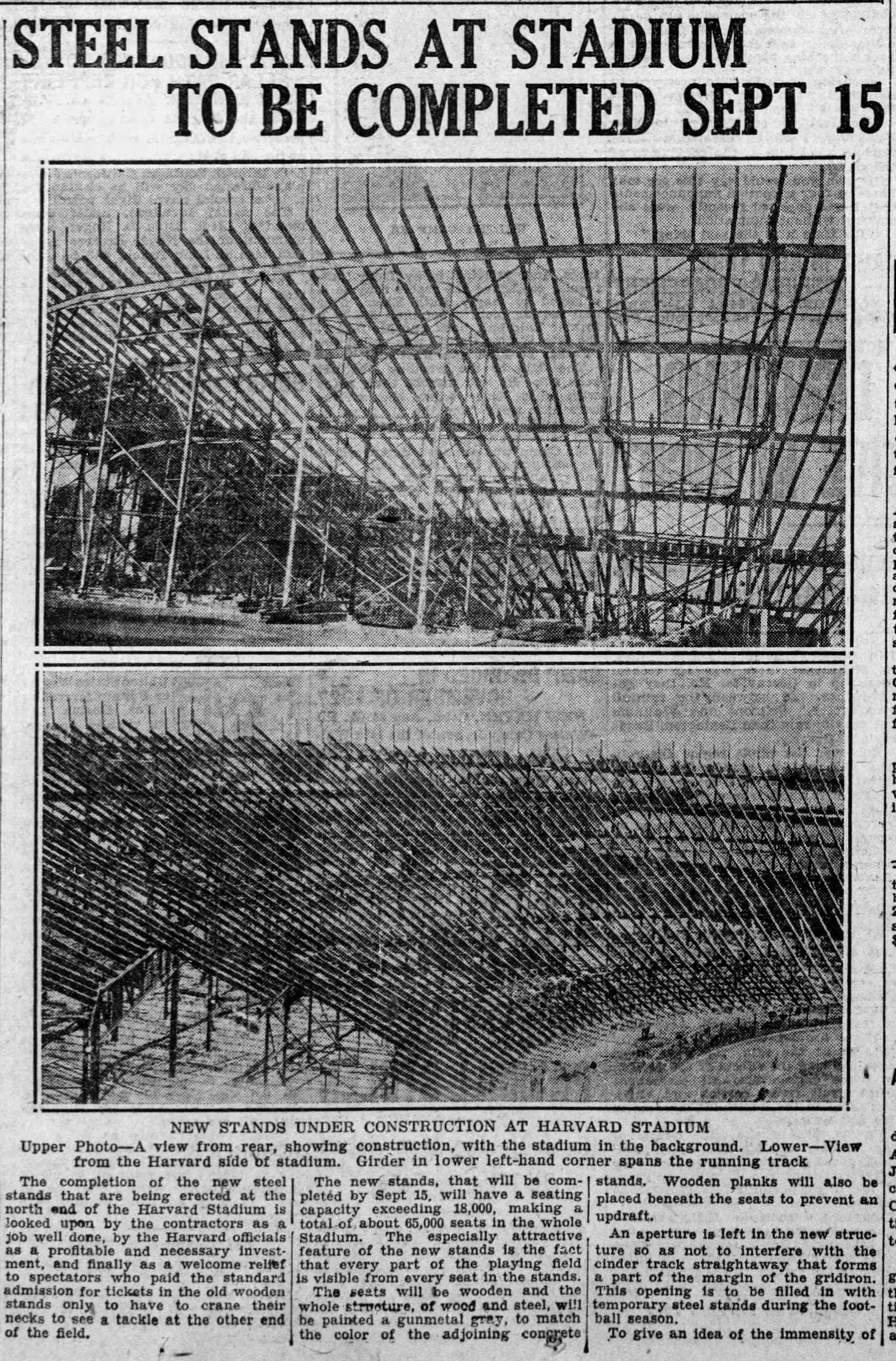

There were not enough seats to go around, and then disaster struck. The Building Commission notified Harvard they were condemning the temporary wooden seating installed for big games. Temporary wooden seats were dangerous, with many instances of them failing at college stadiums.

W. J. Bingham, Harvard’s Athletic Director, set to work finding a solution, engaging Gavin Hadden, Class of 1910 and noted stadium designer, to offer alternatives.

Hadden determined they could expand Harvard Stadium to 80,000 permanent seats. Hitting that mark required enclosing the stadium's open end with concrete stands and adding rows on top of the stadium while eliminating the colonnade.

A second option was to replace the temporary wooden stands in the end zone with steel bleachers, which would maintain the current capacity while increasing safety.

The third option was to accept that the 25-year-old stadium's best days were behind it. Harvard could build a new football stadium that, ideally, exceeded the Yale Bowl's capacity. During a March 1929 public debate about Harvard's options, Dr. William M. Conant, a member of the Class of 1879 and a former football player, argued for Harvard to build a 150,000-seat stadium while preserving the current stadium for minor sports. That approach seemed unlikely.

Bingham, the AD, presented the options to Harvard's Athletic Committee, which passed them on for consideration and approval by Harvard Corporation, the school's governing body.

Ultimately, Harvard Corporation decided in February 1929 to pursue the steel bleacher option. The approach cost only $150,000 and left open the option to build a new stadium in the future. Expanding the current stadium to 80,000 would lock Harvard into a solution based on outdated infrastructure that would prevent Harvard from possessing a state-of-the-art facility in the future.

Once they made the decision, Harvard shifted into execution mode, developing detailed plans for the steel seating. The factory-made components arrived in time for installation by the opening game of the 1929 season.

The 1929 team went 5-2-1, tying Army and losing a close game before 85,042 at Michigan while also suffering a blowout home loss to Dartmouth. The finale against Yale took place at Harvard Stadium that year, with approximately 57,000 fans watching comfortably as the Crimson defeated Yale 10-6.

Harvard dismantled the steel stands in 1952 and replaced them with new temporary stands in 1953. Those remained in various forms until being razed in the early 1990s. By then, of course, neither Harvard's football ambitions nor attendance required more seats than the stadium had in 1910. Harvard Stadium had come full circle and returned to being a U.

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to donate a couple of bucks, buy one of my books, or otherwise support the site.

Great final line, Tim.

After the Stadium was built, Walter Camp's avuncular image cracked a bit, enough to let some hitherto unknown sense of humor emerge. He wanted to legislate a wider field into the Rules, which would instantly obsolete the place. When I visited in '73, I took photos of its ivy-covered arches. Recent photos show its removal ..